[Warning: this post is very-long and graphics-intensive]

We had an interesting debate going on in the comments to this post regarding inequality, but very specifically on racial inequality in Malaysia. I’d been meaning to post on the data underlying my arguments in that debate, so here it is even though a couple of months late.

It’s been a central pillar of public policy since 1970 to embed affirmative action in the economy along many dimensions, from education to corporate ownership to public procurement. What success any of these policies have had, has to be tempered with the inefficiencies caused by tampering with market forces. There’s certainly a case to be made on both sides of the fence, but much of these tend to descend into emotional and value laden arguments, and not really economic ones.

In any event, I don’t propose to rehash any of these debates, except to lay out what the data on incomes actually says in chart form, and what I think it might all mean. All the data is taken from the EPU website (see the link at the end of the post). The only transformation I’ve done is to inflation adjust the data for some of the charts (clearly marked).

The data covers mean household income from 1970 to 2009, and is sourced from household income and expenditure surveys, which are conducted periodically but not, unfortunately, on an annual basis. Clicking on any of the charts should take you to a larger version.

So without further ado:

Except for the obvious recession periods (1985-1987, 1997-98), incomes of Malaysian households have generally risen (first chart above, in RM). The second chart above shows the ratios (by ethnicity) against the average Malaysian household, while the third chart is the same as the second, but omits foreigners for a closer look at the data trends.

The big variation in incomes of foreign workers can be largely explained as changing demographics – in the post-independence era and before the drive towards industrialisation, foreigners were primarily high income expatriates running or working for foreign owned companies, or in government. As manufacturing and estate activities increased, there was a dramatic shift towards low wage foreign labour, hence the drop in average foreign incomes.

One thing that’s clear though is that income by ethnicity is converging on the Malaysian norm, with two distinctive periods – 1970-1987 and from 2002-onwards. In the period in between, income ratios by ethnicity were largely stable, with a tendency towards divergence. This is true not only of average households across the spectrum, but also true within income stratas as well.

For example, here are the ratios for the middle 40% of income earners by ethnicity relative to the whole:

For all intents and purposes, the chart above is very nearly identical to the one before using aggregated incomes.

More interestingly still, we can see where the idea that inflation has eaten into take-home pay in recent years has come from (inflation adjusted incomes; 2000=100):

It’s not true of Malaysian households generally and definitely not for Bumiputera households, but it is specifically true for Chinese households and somewhat so for Indian households. In fact real incomes have fallen from 2002 onwards for Chinese households and from 2004 are effectively flat for Indian households.

Take away the impact of the 1997-98 recession, and real incomes for Chinese and Indian households have barely increased since 1997. Real incomes in 2009 for Bumiputera households on the other hand are as much as a third higher than in 1997.

Again this is across the board, though these trends appear to be stronger for high and middle income households than they are for poor households, where incomes even for Chinese households have shown some increase, at least up to the advent of the Great recession (inflation adjusted incomes; 2000=100):

So the conclusion that can be reached is that inequality by the race dimension is gradually being reduced and is at a historical low.

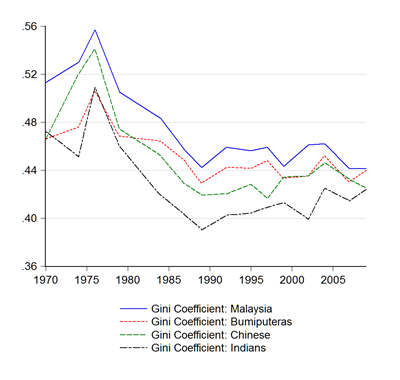

Unfortunately, we’re not so lucky with overall income inequality:

Again across the board – income inequality is a Malaysian phenomenon, and not wholly a cross-ethnic phenomenon. While income inequality has fallen generally from an average around 0.50 in the 1970s to around 0.45 since 1987, there has been little to no significant improvement since.

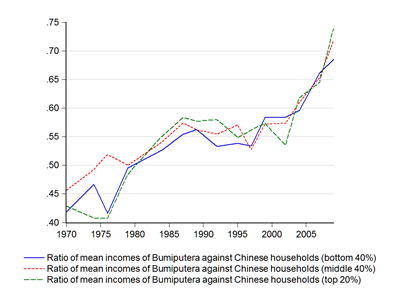

There does however continue to remain inter-ethnic income disparities (here, Buimputera households against Chinese households by income strata):

From around 40%-45% of Chinese household incomes in 1970, Bumiputera incomes have closed to 68%-74% in 2009. The gap has been closed to the smallest level historically, but its still there.

Nevertheless, questions remain:

- How have Bumiputera incomes gained so much, and just as importantly, why were the gains confined to pre-1987, and post 1997?

- What explains the stagnation in inter-ethnic income ratios between 1987-1997?

- Why, despite poverty alleviation schemes which appear to have been successful, has this not resulted in reductions in income inequality measures post-1987?

- Why did Bumiputera incomes continue increasing in the 2000s, yet Indian and Chinese incomes stagnate or retreat?

There’s obviously the impact of NEP and post-NEP policies, but that explains only some part of the convergence in the inter-ethnic income ratios, but not fully. These policies continued to operate throughout the sample period, but the biggest impact appears to have been pre-1987, and less so afterwards.

The fact that income growth and ratios behaved so differently across time suggests that affirmative action policies aren’t the main driver for income convergence – quite a few measures were rolled back in the aftermath of 1997-98, yet this period marks the beginning of the sharpest income gains for Bumiputera households.

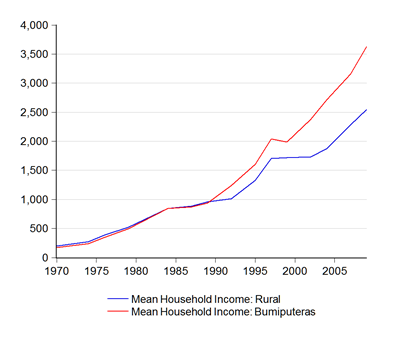

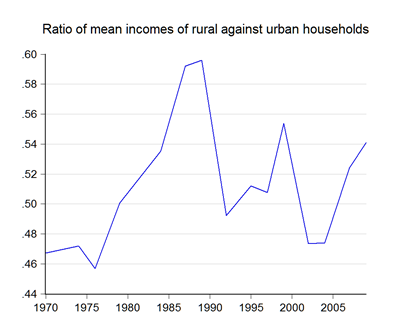

My working hypothesis revolves primarily around commodity prices (particularly rubber and CPO), but even that’s an imperfect measure going by these next two charts:

Up to 1987, rural incomes and Bumiputera incomes were virtually synonymous. But after the 1987 recession, Bumi incomes also began to have a growing urban component (first chart). The second chart suggests much the same story – if agriculture growth was driving Bumiputera income gains, the biggest impact was pre-1987 and less so afterwards.

Here at least we have a partial explanation of why Bumi income ratios stopped climbing after 1987 – urban income growth on average outstripped rural income growth from 1987-1997, helped along by weak commodity prices in US dollar terms after the coordinated forex intervention following the Plaza Accord. Commodity prices only began climbing again (in inflation adjusted terms) after about 2000.

Nevertheless, we’re still left with the mystery of why Chinese and Indian incomes (presumably more concentrated in urban communities) stagnated while Bumiputera income gains began climbing again post-1997. Commodity prices certainly were a factor here, but not the whole story given the increasing urban component of Bumiputera incomes.

Affirmative action policies were also a factor, but also nowhere near the whole story, especially considering the rollback of some of the equity ownership criteria after 1997 and liberalisation of some economic sectors.

One way to maybe resolve these puzzles is to look at the ethnic makeup of the labour force in different economic sectors, but I don’t have that data. What data I do have suggest somewhat perversely that Chinese incomes are more strongly affected by agriculture than by manufacturing, which doesn’t make any sense to me.

So we’re left with more than a few conundrums for people to continue arguing over…and fertile research grounds for aspiring PhDs.

Technical Notes

- Data on household incomes from the Economic Planning Unit

- Consumer price index data from DOS (spliced series rebased to 2000=100)

To quote you" One way to maybe resolve these puzzles is to look at the ethnic makeup of the labour force in different economic sectors, but I don’t have that data."

ReplyDeleteReply: I have seen the data and job mobility/employment (along etnicity) has NOT played the role in distributing gains through economic growth.

Household incomes is only 50% of the total incomes as measured by GNI.Thus simple explaination is..Bumi income is primarily wages n other incomes.Whereas since 80s non bumi hv increased participation in corporates.So their income profile is more varied ( not only income via dividends).

ReplyDeleteFor true understanding of this phenomena..corporate ebitda (operating surplus) shld be factored in.Tho not divvied..the income is retained.

Hey,

ReplyDeleteI've seen the data before on EPU but this is the first time I've seen it as a time series chart. I usually end up just taking the 2009 number.

I'm not a very big believer of Kutznet's Inverted U theory of inequality and development so I'm going to approach it more from a demographer's POV

The NEP policies in the late 1970s probably took half a generation to realize its gains. It takes that long for kids - who weren't in school at that time (Bumiputra majority?) - to get educated and enter the workforce.

The racial-inequality post 2000's *could be* due to the declining fertility rates in the Chinese and Indian segment of society since 1970s (a coincidence, I'm sure) which caused the workforce composition among racial lines to change considerably.

But if you really want to take another form of argument which is not AA, you can just say that most of the industries post China WTO accession in 2001 are owned by the Chinese and faced too much cost competition overseas over the past few years compared to Bumiputras and Indians who are more domestic-oriented (not enough data to substantiate that though).

Between the two arguments, I prefer the former only because I've got *some* statistical evidence to back it up.

I hope someone has a better explanation other than AA :)

@anon 2.02

ReplyDeleteI'll take it as true then - where did you see the data?

@anon 2.15

That's a possibility, though I don't think its as simple as that. From some of the data that I have, Chinese incomes are indeed more exposed to volatility and Bumi incomes have a higher portion of wages. But Indians have an even higher portion of income in wages, so the different income trajectories post 1998 doesn't make sense using wages alone as an explanation.

@Jason

...but, Bumi fertility rates are dropping as well? Household sizes are falling across the board, not just for Chinese and Indian households. Or are you thinking of this on a per capita basis? The number of income earners per household isn't all that different.

I prefer your second explanation, as China competition could be affecting profit margins for manufactured exports, but having the opposite effect on primary exports. But as you say, trying to prove that is tough.

Did/Does PNB (through amanah sahams) have any significant impact on Bumi income gains through the years? I'm thinking Bumis have slowly become more and more able to invest their savings over time.

ReplyDeleteANI

Bumi fertility rates peaked much later than the Chinese and Indians (I think). But that's more likely true given the differences in income...Crude Birth Rates of Bumi's have always been significantly higher since the 1990s - earliest data point btw.

ReplyDeleteThe effects of this in workforce demographics won't show up until a couple of decades later.

The sudden boost to the educated composition - the hypothesis being that a large proportion of the bumi population had a sudden upward education shift in the 1970s/80s - means that the domestic income pie would be shifted to them just by dint of demographic pressure.

But I can also understand why my other explanation also makes sense, but you have to wonder why all these factors managed to converge on one particular decade (whether demographic pressure or China's WTO accession)

If there is data of the operating surplus..think it will show the trend of non bumis shifting from household incomes to corporate incomes.The income tax structure encourages maximisation of tax expendable "perks" which are not registered as personal income.Similarly profits are well protected frm tax via accelerated capital allowances and retained.

ReplyDelete@ANI,

ReplyDeleteFor the majority of Bumi households the answer is no...I have that data at least. Most households, especially lower income households, just don't save enough.

@Jason

I think you're probably right, as far as why Bumi incomes have continued to climb. Damn if I can figure out a why to prove it statistically though.

We're also looking here at multiple issues, not just one as implied by converging income ratios. I think the second explanation does a better job in terms of explaining stagnant Chinese incomes, though its still a puzzle given higher Bumi participation in secondary and tertiary economic sectors. I would have thought they'd be affected too.

@anon 3.45

Thanks. If I ever get hold of the datasets, I'll see if I can test that hypothesis out. Absolutely agree on the incentives embedded in the tax regime.

Sorry, that should be "way to prove it" not "why to prove it".

DeleteI've got (another) hypothesis on that one, if we are on the China argument.

ReplyDeleteSimply, corporate incomes are more variable than sticky wages. This would probably explain why real Chinese incomes stagnated over the 2000s relative to other ethnic groups. It's hard to comprehend that anyone will put up with stagnating real incomes when the rest of the economy is growing.

hishamh,

ReplyDeleteif of any help..

http://is.gd/rZIoUa

One reason possible for the non-bumi income stagnant growth post '97 is the substantial outflow of labor force (skewed to non-bumi group) who are consists of educated and higher income group.

ReplyDeleteIf I am not mistaken from the official figure (2000 till present), the number is exceed 1m and over 80% are non-bumi.

@Walla,

ReplyDeleteThanks, I'll have a look at that.

@anon 9.37

Certainly within the realm of possibility, though the World Bank figure is stock, not flow.

Their actual baseline estimate is around 250,000 leaving from 2000-2010, of which only only about a third are in the high income category. Second, based on their research both the rate and intensity of brain drain has actually come down, not gone up, since 2000 compared to the decade before.

Just my two cents and some questions.

ReplyDeleteFirst of all, aren't household income surveys done based on self-reported figures? That won't affect the major trends, but it will explain the peaks and valleys a little.

Since we are talking about trends in household income here, it should be noted that the recent DOSM studies actually did the household income and expenditure surveys together (in the past, the latter was done separately together with the labour force surveys). The real wealth that we need to adjust, other than for urban and rural differences, is in their consumption power.

I have an idea about the recent downward trend of the average household income for the Chinese and Indians. Someone said that employment by ethnicity has little effect, but I think we should be looking at the different industries and track their changes in contribution to GDP. Manufacturing's share of GDP went from 31.4% peak in 2000 to 25.6% in 2010. Mining and quarrying went from a peak 14.4% in 2005 to 12.3% in 2010. Construction is down too, but the services and agriculture are making a comeback in the past 5 years or so.

I think Hisham's original suspicion is correct, and to a certain degree, so was Jason's. Our country's economic activities are changing, and manufacturing is losing its shine (to Vietnam, China or whatsoever). Factory line workers can find other low-paying jobs, but their owners and bosses and investors will find it difficult to replicate their lucrative endeavors during their heydays. I think the SMEs are hit bad.

The stagnant Chinese and Indian incomes should be happening at the middle or upper levels, but the gini co-efficient trends shows a conflicting picture between the two races (perhaps affected by Tony F alone? Haha...). Perhaps what is needed is some data on retrenchment and new jobs by ethnicity, to see the flow of workers, as well as capital or corporate income flows. I don't think any wealth is hidden or absorbed elsewhere.

How much of the Malays' household income is being secured by mostly government and glc jobs (plus their increased salary scales) cannot explain for such a gain in income inequality. I think the strong growing trend of climbing household income is the NEP at work, but the income inequality picture should put a damper on its success.

For the Crude Birth Rates (CBRs) and mortality rates, data are available back to the 1960s (Peninsular only-lah). The CBR for the Bumiputera started to climb since late 1970s while the others steadily declined. For the Bumiputeras, CBR reached a peak of more than 35 births per 1,000 population in the mid 1980s. After that, the declining trend is similar to that of the other races. The Chinese of course, had it much worse. National TFR is 2.2 in 2010, with the Malays being the highest (2.6). The Chinese has fallen below replacement levels since 2005 (1.7) and the current Total Fertility Rate for the Chinese is 1.5.

ReplyDeleteHow does this impact household income apart from ageing families? The crunch of the non-Malays must be great indeed as their average income falls and they needed to support more non-working family members. All things being equal, I think the household income average will narrow because of demographic factors, since NEP is levelling the playing field and state-driven economic initiatives will create more distortions to the market (reducing the impact of capital-rich individual or corporate players).

Good comments. I'm struggling trying to figure out a way to link the evidence with the income trends. Sector size relative to GDP as a basis won't really work because they're ratios, and we need something to explain changes in the levels of incomes.

ReplyDeleteWith respect to birth rates - two problems here. One is that income is negatively correlated with fertility (higher incomes cause lower birth rates), and second the lag effect of family size on future incomes. So its two way causality, but distributed across time. Tough to model, that one.

Agreed. We can still chart it to GDP at current prices, and check if there is a correlation. Trending wise, manufacturing's value is also stagnating below RM200,000 million between 2007-2009.

ReplyDeleteI think average household size is important, but without the spending pattern, specifically on assets and liabilities, we cannot really capture the wealth picture. Average household incomes that doesn't go into property, savings and other investments are in reality transient.

On the other hand, I won't sweat too much about income inequality because gaps are narrowing and Bumiputeras will always be disadvantaged when it comes to averages because of population size and geographical spread (as affected by the dominant industries).

If I may suggest, does it have anything to do with the revamp of civil service salary in mid 2007? It could be one of the factor along with impact of NEP and better educated workforce entering higher paying jobs.

ReplyDeleteSorry, i'm not economist and don't have any data to support the above. Just passing by this blog.

@anon,

ReplyDeleteI've tried regressing incomes against current dollar sector size - that's where I got the strange result that Chinese household incomes are a factor of agriculture sector growth. Manufacturing wasn't statistically significant. I'm not ready to give up yet though.

With respect to income gaps, I'm more concerned about top to bottom income inequality than I am racial inequality. Having said that, I'm not totally in favour of repealing the NEP just yet.

@Poobalan,

The civil service pay revisions aren't likely to be a factor. One, it came much later than the changes in the income trends which began in 1997-2002, and two, as big as it is, the civil service only makes up 10% of the working population.

HIS only measures income i.e wages,rentals,interest n dividends.And the total is only 50% of the GNI.So who owns the other 50%?

ReplyDeleteHisham,

ReplyDeleteref Anon 5:57 June 29 on GNI.

Could you clarify how does GNI or operating surplus factor into household income?

Greetings HishamH

ReplyDeleteThere are a few observations which I wish to make regarding the contention of narrowing inter-ethnic income inequalities and widening intra-ethnic income inequalities.

1.with regard to the income data used in computing the GINI, how certain are we regarding accurate disclosure and verifiability. For instance, income from non-wage sources such dividends from equities, capital gains from property disposal etc, are they disclosed under income per se? If not wouldn't a family receiving a one-off dividend of say RM8,000.00 from a RM100000.00 ASB investment be better off than one not receiving such a windfall but within the same income bracket.

2. Quite a number of commentators missed the point that the period from 2007 to 2011 witnessed a dramatic increase in the price of primary commodities namely oil palm and rubber and to a lesser extent other agricultural produce and minerals. Given the predominant Bumi participation in the agricultural sector, would that increase in global prices not have a corollary net positive effect on incomes which accounts substantially for the catch-up effect in terms of inter-ethnic income measures. Conversely, the relatively undervalued nature of the Malaysian ringgit (which by default made exports cheaper but imports expensive) deterred the import of capital goods for the technological retooling of Chinese owned SMEs leading to a diminution in productivity and a loss in competitiveness. Thus, given the Chinese predominance in this sector would that not have a negative impact on incomes?. Additionally, how much has the loss of estate employment and the displacement cheaper foreign labour has impacted on Indian income levels post 1997 and especially post 2002 given the "inelastic" profile of Indian labour (with its predominantly labour intensive bias)?

4. As in my previous comments in your earlier post, I have noted that the pro-market liberalisation policies and the downsizing of the NEP initiatives particularly by Brother Anwar bin Ibrahim were largely responsible for 1987-1997 (3).

3. The nature of the argument seems to be that income differentials are the ultimate determinants of equality is flawed simply because there other variables (1) at play that determine the economic well-being of each ethnic relative to one another. Granted they are difficult to 'standardise' for comparative purposes due to differing valuations and other such shortcomings, they are nevertheless indicative of the overall inequality/equality picture we are trying to piece together.

One such place to begin with in piecing that jigsaw is provided in the article below:

Muhammed Abdul Khalid: Household Wealth in Malaysia: Composition and Inequality among Ethnic Groups:

Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia 45(2011) pgs71 - 80 available online

the arguments of which leaves me feeling and wondering whether Anand's(2) seminal observations in 1977 are still as valid today:

"When several of the characteristics associated with high degrees of poverty

are taken together, we find that the chances of being poor can become extremely

high. Thus, for example, a Malay farmer in rural Kelantan has a worse than

three-fourths probability of being poor."

1.Muhammed Abdul Khalid: Household Wealth in Malaysia: Composition and Inequality among Ethnic Groups: Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia 45(2011) pgs71 - 80

2.Anand,S: Aspects Of Poverty In Malaysia

Review of Income & Wealth; Mar1977, Vol. 23 Issue 1, p1-16, 16p

3.Household Income Distribution Impact of Public Expenditure by Component in Malaysia H. Mukaramah*, Ahmad Zafarullah Abdul Jalil and Nor’Aznin Abu Bakar:International Review of Business Research Papers

Vol. 7. No. 4. July 2011 Pp. 140-165

Warrior 231

@anon 5.57

ReplyDeleteIt depends on ownership, for which we don't really have the figures. But based on par values, it would be about 20%+ bumi, 40%+ Chinese, and 30% foreigners.

@anon 1.07,

Short answer - household income and operating surplus are part of GNI. Unfortunately, DOS data doesn't go back further than 2000, and until they provide the back-series, it would be hard to see how corporate profits factor into income shares over time.

@warrior 231

ReplyDelete1. The data includes all sources of income, not just wages. If there is under-reporting I would expect it to be systemic, i.e. Bumi households are as likely as Chinese or Indian households to not declare non-wage income.

2. I'm interested in the role of commodity prices as well, though I'm beginning to think that's they were primarily a factor in the initial catch-up phase (1970-1987) and subsequent stagnation, than they were for the second catch-up phase. For one, inflation adjusted commodity prices are well below their 1970s peaks, and second the increasing urban component in Bumi household incomes.

Regarding the impact of exchange rates, there was a substantial revision of import categories in 1998-2000 which makes pre- and post-1998 data difficult to compare. But since there was no substantial drop-off in total import values, I don't think this is a big factor. It would also be hard to disentangle the terms of trade effects from the competitive effects (such as Jason and I were discussing above).

With respect to Indian incomes, that's a good point and something to add to the list of possible factors.

3. Another possible candidate, though I should note that there continued to be liberalisation post-1998. I'll need to hunt down the paper for review - there's the possibility of omitted variable bias with studies of this sort.

4. I'm under no illusions that income alone defines equality, and I'm also well aware that wealth inequality is substantially higher. Muhammad also emailed me to point out that on a per capita basis, the income differentials are substantially wider than they are on a household basis. I'll forbear from commenting more until I have a closer look at the data.

One other point to make is that handling wealth inequality and the high income inequality within communities (and not just across) will require a substantially different set of policy measures than NEP style affirmative action.

The question is, do we as a society feel strongly enough about income and wealth inequality to adopt the type of measures that have proven to be effective? My sense is that we are not. Attitudes are changing, but not to the point of acceptance yet.

Re: Warrior's 4th point.

ReplyDeleteI don't have a very legitimate source at the moment (nor do I have time to look for it right now), but I think the narrowing of the wealth gap in the post-1985 recession had more to do with a shift in industrialization policies.

The post-1985 recession policies had reduced our reliance on commodities as a substantial driver of growth. National account numbers do suggest that anyway.

Some commentators have suggested as well that Malaysia's growth path (and the other crisis countries) in the early 1990s were unsustainable and that 1997 was a correction to that, hinting at some banking/capital flow oversight deficiency during the period. But like my previous point, that's also pretty hard to prove with the available data.

Jason, with respect to commodity prices, I think the causality runs the other way. With the Plaza Accord depreciating the value of the USD, Malaysian commodity exporters were hit with lower terms of trade while at the same time substantially increasing the incentives for Japanese manufacturers to shift production overseas.

ReplyDeleteCouple that with Look East policies and a deliberate shift towards industrialisation, we have a simultaneous dis-emphasis on agriculture and a boost to manufacturing.

Which of these particular factors had a greater effect? I don't know.

Dear Hisham..

ReplyDeleteUr estimate of 20% Bumi,40% NonBumis & 30% Foreign of the OS..Govt hv zero?

@anon 6.32

ReplyDeleteThat's what the data from SSM says.