The pace of my blogging has dropped off substantially the last couple of weeks, for which I apologise. I've been busy in Sarawak for the past week, and will be in Dubai until next month, so normal posting will only resume from about the first week of May or thereabouts (depending on how I deal with the jet lag). This post will have to do for now.

I’ve noticed that I’m getting a lot of Google hits about Malaysia’s national debt position and fiscal deficit. Since I haven’t done an update in a while, what’s the position with government finance and Malaysia’s national debt right now?

Up to the end of last year the national debt reached RM362 billion compared to RM306 billion in 2008, with about half the increase due to planned expenditure under the 2008-2009 budget, and the other half coming from the combined stimulus packages:

That actually comes in about RM18b below my rough forecast, which isn’t bad at all. Up to 22nd April, a further net RM16.64 billion was borrowed, which was a little off the pace of last year and includes RM10.9 billion in redemptions (mostly in April). That puts total national debt to date at around RM378 billion, or a little over RM13,000 per capita.

I put my thoughts on the government’s debt position in a recent post and won’t repeat my comments on that here.

However, as an interesting side note, there was a very short and ill-publicised report that the government has already broken fiscal discipline to the tune of RM12 billion over and above the 2010 budget:

An additional allocation of RM12 billion will be approved for the 2010 Budget, said Second Finance Minister Datuk Seri Ahmad Husni Ahmad Hanadzlah.

He said the allocation was to implement the six National Key Result Areas (NKRA) under the 10th Malaysia Plan (10MP) and to cater for additional funds sought by various ministries.

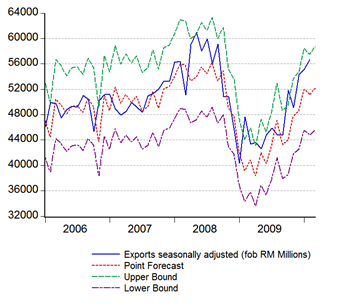

That’s an additional 6.3% over the planned budget and almost wipes out the projected savings over the 2009 budget. The only saving grace with this is that the government has almost always underestimated its operational spending in its budget proposals – so this additional outlay is just par for the course (budget proposals against actual realisation, RM millions, 1998-2010):

To offset this profligacy somewhat, the Treasury has, apart from last year, also systematically underestimated revenue every year as well. I think revenue will again surprise on the upside this year – 6%-7% GDP growth is well within reach – which will help defray the additional expenditure.

Technical Notes:

- Federal Government finance and public borrowing data from BNM's February 2010 Monthly Statistical Bulletin

- March/April 2010 public borrowing data from BNM's FAST

- Budget estimates from various copies of the Ministry of Finance Economic Report