There’s quite a bit of gloom in the air these last few weeks. The plunge in oil and other commodity prices, capital pulling out of emerging markets, and currency turmoil, have people getting very worried about growth prospects next year. There doesn’t appear to be a bottom yet on oil prices, and it’s anybody’s guess where all this will end up.

In Malaysia’s case, oil price depreciation and Ringgit depreciation seems like one piling on the other – the latter is making things worse (Malaysians feel relatively poorer), on top of the drop in oil and gas revenues. But conflating the two like this is wrong. The depreciation of the currency is in fact a required and necessary result of the drop in oil prices.

If the Ringgit had stayed where it had been (about MYR3.20-3.30 to the USD), the full drop in oil prices would have been transmitted directly and with full force into the domestic economy. The approximate 8% depreciation of the Ringgit over the past few months partially mitigates that income shock. Since sales of oil (and gas) are denominated in USD terms on the international markets, a cheaper Ringgit partially cushions the revenue drop in local currency terms.

Consider that oil & gas make up about 20% of Malaysian exports; commodities as a whole about a third. That means that the drop in oil prices and the depreciation of the Ringgit have been nearly symmetrical. If anything, the Ringgit hasn’t dropped far enough – my estimate is that it should be at least 3%-5% weaker. Or to put it another way, the Ringgit is rather counter-intuitively, stronger than it should be. Or not – 80% of Malaysia’s oil & gas exports are either LNG or downstream petroleum products, which are less sensitive to crude oil prices or only follow with a substantial lag.

Note also that the NEER (nominal effective exchange rate for the uninitiated) has not dropped anywhere near as much as the USDMYR (USDMYR and NEER indexes; 2000=100):

That suggests the last few months currency action has largely been a USD movement rather than weakness in the MYR.

There’s also the flip side that the lower Ringgit should in theory provide a boost to non-commodity exports. In this case though, I’m a bit leery of depending on this as global demand growth outside the US and UK is pretty weak, and because again this is largely a case of Dollar strength more than Ringgit weakness.

The last point I want to raise is this: Bank Negara’s international reserves have been slowly declining over the last few months (RM billion):

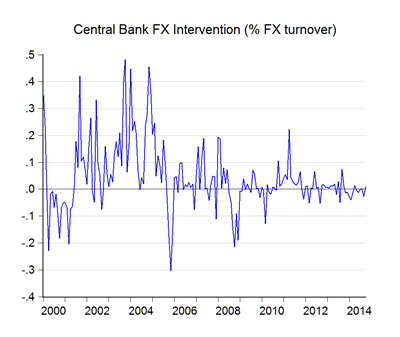

Some have been interpreting this as central bank intervention to support the Ringgit value. (As an aside, reserves actually rose in October; don’t sweat it, BNM marks its reserves to market every quarter, and a decline in the Ringgit would boost reserves in local currency terms). My view is a little more nuanced – the drop in reserves is just too small to make that conclusion (change in reserves as ratio to FX turnover 2000-2014):

Contrasted with the pegged FX regime of the early ‘00s, reserve movements over the past four years are just too minor to affect the FX market. Rather, what I think is going on here is that BNM is simply trying to ensure that there’s enough USD (and other currency) liquidity in the interbank market to ensure, in their words, “orderly” market conditions.

From a practical perspective, I think they’re targeting the USD bid-offer spread rather than the level of the Ringgit. For the layman, what this boils down to is this: you are able to buy any currency you want, without the banks or money changers gouging you (too much) on the difference between buying and selling prices. Alternatively, it could be viewed as they’re simply supplying USD to the market if the banks start running short.

The bottom line is that BNM is not and will not be “defending” any level of the Ringgit. And if they’re not willing to spend reserves on it, you can forget the interest rate defense (which doesn’t work anyway).

Technical Notes:

- FX data from the Pacific Exchange Rate Service

- Reserves and FX market data from BNM’s October 2014 Monthly Statistical Bulletin

Wahid has been Nonchalant about the Drop in Oil Price saying that Malaysia is truly diversified that it will have minimal effect on the economy. Would that be the case if the Oil Price drop to US$55? How about some Scenario testing based on US440..USD50..US60 oil price?

ReplyDeleteThe government seems to be unfazed by the latest developments.

DeleteI guess that a sovereign downgrade would focus their minds wonderfully!

@anon 10.49

DeleteWe've done some sensitivity analysis. Rather surprisingly, the fiscal situation doesn't deteriorate that badly, even if you go down to USD40 per barrel.

@anon 5.57

DeleteMoody's is doing their credit review about now (met them a couple of weeks ago), so we'll know shortly. S&P does their review around May-June, while Fitch does their's around June-July.

It's unlikely we'll be downgraded immediately - more likely to be put on negative watch. Also, if we're downgraded, so should Mexico (same credit rating, slightly higher exposure to oil & gas). I don't know what the rating cycle for Mexico is, so that could come before or after Malaysia's.

I dunno, Hisham. Are we in a strong enough financial position that we can afford to stare down the prospect of a ratings downgrade?

DeleteThe government says that the Malaysian economy has diversified away from an over-reliance on oil and gas, palm oil and other commodities as the primary sources of revenue.

The export statistics don't seem to show this, unless I am missing something.

From what I read in the Singapore papers about the Singapore economy and the reports produced by Singapore-based economists, it seems that the major drivers of the economy there will be services.

I don't see the Malaysian economy transitioning to a services-dominant position any time soon, which means that it will still be dependent on the vagaries of commodity cycles.

@bee farseer,

Delete1. Average size of the services sector (i.e. share of real GDP) in the Malaysian economy (2011-2013): 55%

2. Average growth contribution of services (2011-2013): 68%

The same numbers for Singapore (2011-2013) are 65% and 77%.

BTW, here's one dirty little secret about ratings upgrades/downgrades: they usually lag the market, because credit relevant events don't always conveniently conform with the credit ratings review cycle.

DeleteSo really, it's the judgement of the market that matters, not the fact of an upgrade/downgrade. A ratings change is more a confirmation of what's already happened. As long as the markets stay steady, a ratings change will have little impact.

The only exception to the above would be when ratings go from investment grade to junk (or vice versa), because of the impact on investment mandates. Even at A-, we're miles away from that.

If the Ringgit had stayed where it had been (about MYR3.20-3.30 to the USD), the full drop in oil prices would have been transmitted directly and with full force into the domestic economy. The approximate 8% depreciation of the Ringgit over the past few months partially mitigates that income shock.

ReplyDeleteCan U explain more? Msia will get excess liquidity if MYR stayed at 3.2 to USD? What is income shock?

@anon 3.17

DeleteEasiest way to explain is with an example:

Assume you sell a good on international markets for USD100. At a RM3.20 conversion rate, that means your revenue is RM320.

Say the international price drops 20% to USD80. If the exchange rate stays the same, your income drops the same proportion - by 20% to RM256, or RM64 less. That's the income shock.

But let's say the exchange rate also depreciates, but by 10% (for easy calculation, assume RM3.50 to the USD). That means the same 20% drop in the international price results in an income drop to just RM280, or RM40 less.

With Ringgit at RM3.20, you've lost RM64 in income. With Ringgit at RM3.50, you've lost a smaller RM40 in income.

The depreciation of the Ringgit means your income loss has been lessened.

BTW the interesting thing is what happens to other goods, where prices haven't fallen.

DeleteTake the same example above, but substitute a different good, also selling at USD100.

Assume the changes in the exchange rate occured, but international prices have not changed. Your income before is RM320 but your income after is RM350, a RM30 increase.

Depreciation of the Ringgit means not good for 1MDB debt.

ReplyDelete