I’ve been planning on posting this for a while now, but came across this article this past weekend, which provides the perfect entree (excerpt):

Property market bubble set to burst, says think tank

PETALING JAYA: The property bubble in Malaysia is set to burst, but the government must resist the temptation to intervene and allow market forces to coordinate supply and demand, says a think tank.

In an interview with FMT, the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs’ (IDEAS) senior fellow, Carmelo Ferlito explained the two “economic dynamics” which have resulted in the current property situation in the country, where the prices of homes are beyond the reach of most and the oversupply of such homes, has led to many being left unsold.

Figures from the National Property Information Centre (Napic) have indicated that as of the first quarter of 2017, some RM10.08 billion worth of residential units are unsold in Malaysia. This figure does not include serviced apartments, which have since 2015, been classified as commercial properties.

For some time now, the discourse over unsold properties in the market has focused on two key contributing factors – the prices of homes that are too high and the difficulty buyers have in obtaining bank loans.

What hasn’t really been explained, says Ferlito, was why the prices of property in the country are as high as they are.

“Malaysia is undoubtedly experiencing a housing bubble and the unsold properties are a natural consequence of this bubble.

“This bubble is due to two specific economic dynamics. The first is the natural business cycle, and the second is the intervention by the authorities,” Ferlito said....

Question: What’s a bubble?

Kindleberger1 defines bubbles as “non-sustainable increases in the indebtedness of a group of borrowers, or non-sustainable increases in the prices of [assets].”

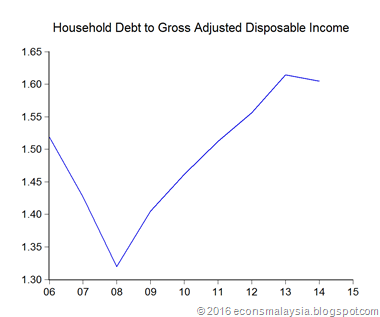

On the face of it, that’s precisely what has happened with both households (as debtors) (Household debt as a percentage of disposable income):

…and houses (as assets) (MHPI; 2000=100):

Seems like a no-brainer. Household debt has increased relative to income, while house prices are well above the 2000s trend, and broken upwards strongly since 2008. Certainly looks like a bubble.

Except, a funny thing happened when I looked at the longer trend of both income and house prices in Malaysia. I’ll have to admit, this took me completely by surprise (1988=100; index numbers):

I used here two different measures of household income – GDP per capita, and average household income (HHI) based on DOSM’s Household Income Survey. And this chart says that even if houses in Malaysia are unaffordable now, by implication they were even more unaffordable a generation ago. Income growth in the interim has more than exceeded house price inflation, and if prices have risen strongly post-2008, they haven’t fully covered the gap that opened up after 1999, a gap that can be seen with both income measures.

I wouldn’t dismiss the undeniable fact that unaffordability is a problem – what was unaffordable then remains unaffordable now, even if the gap is relatively smaller. The distribution of supply remains important as well, insofar as there are differences in demand across different states (driven in part by internal migration). Last but not least, demographic pressures are a big factor too, given that a large percentage of the population is entering prime home-buying age.

But that doesn’t imply a debt/price “bubble”. Based on the above, prices don’t look “non-sustainable”, since they’re within the norm of the past 30 years. Even the debt numbers are poor evidence, because the sample period for which we have data is too short. I’ve tried using state level data where price increases have been the strongest (e.g. Selangor or Penang), but came up with roughly the same conclusion.

Notwithstanding the current property overhang, I continue to remain unconvinced that we will face a housing bust any time soon (2040-2050 is another matter). Quite frankly, Malaysia has seen worse.

Technical Notes:

- Charles P Kindleberger and Robert Z Aliber, “Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises 6th Ed,” Palgrave Macmillan, 2011

- Household Debt data from BNM Financial Stability and Payment Systems Report, various years

- Household Income data from Distribution and Use of Income Accounts from the Department of Statistics Malaysia

- Malaysian House Price Index from the National Property Information Centre; and Monthly Statistical Bulletin from Bank Negara Malaysia, various issues

- GDP per capita data from the Monthly Statistical Bulletin from Bank Negara Malaysia, various issues

- Household income time series data from the Economic Planning Unit

Thank you for the interesting read. Do you think that perhaps a median household income as opposed to average might be a more appropriate? In property reports that I encounter, such as on Singapore/Hong Kong, the prices are often quoted in multiples of median income.

ReplyDeleteThat said I do not think it is a bubble, at least in the usual sense. We might get more insight if we can see the volume trends for first time homeowners vs investors. Another metric would be vacancy rates vs. prices as well. The issue with property prices is far from just a Malaysian phenomenon hence I am skeptical about any proposed measures that claim to work as a long-term solution. -MN

@MN

DeleteI doubt using the median would make a difference, since the trend is roughly the same.

As for who's buying, we've found a strong surge in home ownership for those below the age of 30.

Very interesting analysis. Thanks a lot for that! Definitely agree with you that the property bubble is not as near as many might think.

ReplyDelete