A couple of things were raised last week that I want to address:

Issue 1: The Difference between Operating and Developing Expenditure

I’ve had to explain this at least twice over the last few days, so I thought I might as well spell it out. Malaysia is one of the very few countries that actually subdivides spending between operating and development expenditure – actually, I think Singapore is the only other country that does this. MOF keeps these accounts entirely separate (I’ll touch on how they intersect in a bit), whereas most other countries consolidate the two.

Here’s the main distinction between the different accounts:

- Operating expenditure (OpEx) is recurring expenditure related to the running of the government, and is funded by revenue. Salaries, pensions, interest payments, office supplies and the like fall under this broad category.

- Development expenditure (DevEx) generally refers to capital expenditure, but also covers things that are expected to bring a long term economic return. Schools, roads, hospitals and such, fall under this category. Development expenditure is partly funded by revenue whenever there’s a surplus on the operating budget, but mainly funded by borrowing.

For you accounting types out there, OpEx is the stuff that goes on your income/expenditure or profit/loss statement, whereas DevEx causes changes to the balance sheet.

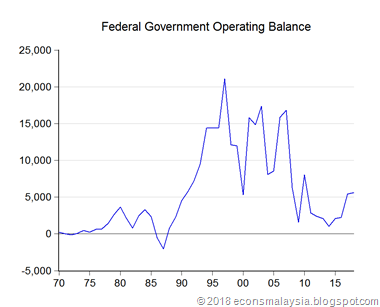

The difference in funding is important, and is termed the “golden rule” – you should only borrow for investment, or purchasing assets, and never for consumption. As far as the data goes back, this rule has only ever been broken three times – in 1972, and in 1986-87 (RM millions):

In other words, the Malaysian government has almost always run a surplus on the operating budget, and borrowing has only been used on development or capital expenditure. Of course from a legal standpoint this is only an administrative rule, but it also a highly sensible one and in keeping with fiscal policy prudence.

The reason I’m raising this is because, in the runup to GE14, both sides are accusing the other of promising too much, and potentially “bankrupting” the government and putting government debt growth on an unsustainable path.

I don’t think so, given the contraints I’ve outlined above. Virtually all the measures mentioned in either manifesto refers to OpEx, not DevEx. Neither spending plan is likely to result in an expansion in borrowing, because the development budget won’t actually be affected. Keeping to the Golden Rule means that funding will have to come from either revenue expansion (from raising taxes or from organic growth), or from reallocation or cuts to OpEx. Unfortunately, there’s very limited scope for reallocation under the operating budget, so cuts are the more likely if revenue can’t keep up.

The biggest difference – and inconsistency – is with PH’s proposal to revert back to the old Sales and Services Tax regime (SST) and drop the Goods and Services Tax (GST), presumably at the old rates, though this isn’t mentioned explicitly. The other issue is to implement more efficient procurement and review “mega projects”.

What’s the implication of this? First, that means the more or less RM20 billion reduction in tax revenue will have a negative impact on the operating budget. Second, all the expenditure “savings” will occur on the development budget. The upshot is that PH’s manifesto is likely to result in a relatively smaller deficit than BN’s, but at the price of sharper cuts in OpEx. The government footprint in the economy will be smaller overall, but the delivery of essential services such as healthcare and education could be threatened, as these costs are rising faster than economic growth. From a sector balance viewpoint, this will also likely result in higher household and corporate debt (as happened in the 1990s when the government ran a surplus), and/or slower economic growth.

Pick your poison.

Issue 2: Debt comparisons within the economy

For the second issue, someone raised the question of what is the share of government debt within the economy. Most people would use gross government debt as the primary indicator of national indebtedness, but doing comparisons with this number across the economy is hard, because there’s far less transparency on either household debt or corporate debt.

Let’s try anyway. First, overall government debt (RM millions):

Since this looks frightening, let’s contextualise it by stating the above as a ratio to GDP:

The mean of the time series above is 54.0%, while the median is 49.6%. In other words, government debt is currently roughly in line with historical norms.

Getting household debt numbers is a little harder. BNM reports overall household on an annual basis, comprising both bank and non-bank debt, but I’ve only got figures from 2002:

…and as a ratio to GDP:

Corporate debt is even harder to figure out. There’s three basic components to corporate debt:

- Bank loans

- Capital market debt instruments

- Others (including accounts payable)

Bank loan data is easy to access (but the time series only starts in 2006, due to definition changes), while capital market debt requires a bit of detective work, and some value judgement. For example, what would be the treatment for Cagamas bonds, or for that matter, Khazanah bonds? Second, there’s no time series available, so building one requires more assumptions on categorisation of the available issuance data. As for the third category, frankly I throw my hands up. So let’s just go with the first two (RM millions):

I’ll admit that the PDS estimate in the series above is more than a little fuzzy – it looks about RM100 billion too high, but since this is just to give a flavour of the amount (you’ll see why in a minute), I’ll let that pass. Here’s the same data as a ratio to GDP:

Now, all three put together:

Total debt rose from approximately 200% of GDP in 2006, to a peak of 245% of GDP in 2015. Here’s the attribution table and chart:

| Govt | Hhold | Corp | |

| 2007 | 2.1% | 2.9% | 3.3% |

| 2008 | 3.1% | 3.3% | 4.9% |

| 2009 | 3.9% | 3.1% | 3.1% |

| 2010 | 2.8% | 4.9% | 3.8% |

| 2011 | 2.8% | 5.7% | 4.6% |

| 2012 | 2.3% | 4.4% | 5.1% |

| 2013 | 1.7% | 4.3% | 3.0% |

| 2014 | 1.8% | 3.4% | 3.1% |

| 2015 | 1.8% | 2.7% | 3.5% |

| 2016 | 0.6% | 1.7% | 2.2% |

| 2017 | 1.4% | 2.0% | 2.9% |

From the table, most of the increase in total debt actual came from either the household sector or the corporate sector. Only in 2009, when government revenue was hit by the lagged effect of the global recession, did government debt contribute more than the other two sectors.

Here’s government debt as a ratio of total debt:

The share peaked in 2010 at about 23%, and has been slowly declining after, though not by much. The increase hasn’t been really that much either – just a 2.5 ppt increase in the share of debt.

Of course, most of this is really beside the point. There’s two methodological issues when doing this exercise.

The first is that a significant portion of this debt actually offsets. For example, EPF and KWAP are large holders of government debt, and these holdings should be netted off. For the same reason, retail bonds and corporate housing loans should also be netted off.

The second issue is we’re completely ignoring the other large sector in the economy, i.e. the banks. But bank balance sheets in this instance are an exercise in offsets – they hold as assets the loans that other sectors have to repay, but owe the same sectors the liability arising from the deposits placed with them. The net effect is close to zero (actually something like 90%). Insurers are another case in point – they are big holders of government securities, but their liabilities are the corporations and households who hold insurance policies, who in turn provide the resources to pay off those bonds. This kind of circularity is why aggregating debt (or for that matter, anything else) is an exercise fraught with pitfalls.

On a national level therefore, it makes sense to only use external liabilities as a measure of national indebtedness. But here the direct government share is almost a rounding error:

If we include foreign holdings of government securities (which makes sense in the context of an absence of the circularity argument above), it rises substantially, but not much more than the total debt exercise I’ve conducted above – somewhere around 23% on average. The sharp increase you see there is due to a higher level of foreign ownership post-2009.

Technical Notes:

Most of the data is from BNM’s MHS, except for

- PDS data from BNM FAST

- Household debt data from various issues of the Financial Stability and Payment Systems Report

Dear Hisham,

ReplyDeleteThis post puts things neatly into perspective thanks. If anything people should be more worried about household debt rather than government debt.

It leads me to a (previously unthinkable) follow up question: Since household debt is much higher than government debt as a share of GDP, and the fact that governments always borrow at a lower interest rate (if not negative interest rate eg Germany) would the logical conclusion be for the government to shoulder more debt on behalf of its people?

On a side note, if I as a Malaysian (or a Malaysian corporate) buys MGS, should this be netted off?

C.H.

@CH

Delete:) Welcome to seeing the world through sectoral balances!

2. If you're looking at it from the perspective of one sector against another, no you shouldn't, since the ultimate holder of the liability is different from the asset owner.

But from an external viewpoint, this is done explicitly, which is why no domestic debt owned by domestic actors, is included in the numbers.

Is this the full picture though? What about govt guarantees for private debt? Did you factor that in?

ReplyDeleteRonnie

@Ronnie

DeleteAdding government guarantees on private debt to the numbers above would be double counting, since private debt is already accounted for.

Also, there's a couple more problems:

1. If contingent liabilities of the government are to be included, by rights contingent liabilities of the private sector should also be included. There's little to no information on such liabilities for the household sector, though a bit more for the private sector, primarily contingent liabilities for banks, which are roughly as large as the banking system's balance sheet or about RM2 trillion.

2. Another methodological issue is, should we include just explicit guarantees, or add the implicit ones as well? The implicit guarantees of the government are much larger than the explicit ones, in the region of RM1.5 trillion, or roughly 2.5x as large as official government debt, and 5x larger than explicit government guarantees. Before this frightens you too much, around 100%-200% of GDP appears to be the norm for most countries, or at least those for which information is available.

Me as the future generation, is it the right way for the government to allocate more on OpEx rather than DevEX?. In the budget 2018, I understand that the government try to inject more money on current situation but in the long term or the future generation will causes to bare more debt onward. What is you opinion on this?. The household debt increase based on the graph shows that probably me can't afford to buy a house. Maybe can share your view on this?

ReplyDeleteHaziq

Student

@Haziq,

Delete2. As far as I can tell, most governments tend to spend only about 10% on development, so our level is still pretty good. how that money is spent is a different matter.

2. The level of debt is I think pretty sustainable, and is mostly in line with the ratios in other countries. Again, not something I'm too concerned about.

3. Housing is a mess, and I see few options for fixing the situation. It will require far more coordination between States and Federal than we've seen so far.

Lots of money allocated as development expenditure was disappeared. Just. Like. That.

ReplyDeleteIndefensible regardless you categorize Opex or Adex. Now all these will come to light.

Ronnie

@Ronnie

DeleteYes, I've had some discussions on that. Stay tuned

Hi Hisham,

ReplyDeleteWhat caught my attention was that our national debt to gdp ratio had once hit 100% around 85-86 followed by a rapid decline to around 35% in the next 10 years. What actually happened in 1985 that caused the ratio to rise up to 100% and what caused the rapid rise in gdp in that period (85-95)?

Secondly, why is there a need to maintain certain level of deficit in our account? I have a really hard time wrapping my head around this idea. I hope you can explain this in layman terms. Thanks!

@Nazmi

DeleteA whole bunch of stuff happened in the early 1980s that caused this. First, the Volcker shock:

https://www.thebalance.com/who-is-paul-volcker-3306157

This ended the era of 1970s stagflation, but also hit commodity producers badly, since prices dropped, including those for Malaysian tin, rubber, palm oil and crude oil (Google: Maminco scandal).

Also occurring roughly the same time, TDM instituted a policy of industrialisation, with Japan as the model (the Look East policy). This rapproachment with Japan including taking out loans in Japanese Yen (instead of US Dollars) for development purposes.

In 1985 however, the Plaza Accord turned this borrowing poisonous:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plaza_Accord

The resulting exchange rate moves caused the JPY loans that Malaysia took to balloon in value, since the Ringgit was pegged to the USD.

The flip side to this of course was that the Ringgit became undervalued (as it was dragged down with the USD), and this made Malaysia an attractive spot for Japanese FDI. The Japanese were of course interested in shifting to lower cost manufacturing bases, since the stronger Yen made Japan uncompetitive. That inflow of investment helped push up both actual and potential GDP growth for Malaysia.

As I said, lots of stuff going on.

On your second query, read this:

http://econsmalaysia.blogspot.my/2015/04/living-beyond-ones-means.html

I am very glad to comment on this site with the excellent content of your site.

ReplyDeleteHello Everybody,

ReplyDeleteMy name is Mrs Sharon Sim. I live in Singapore and i am a happy woman today? and i told my self that any lender that rescue my family from our poor situation, i will refer any person that is looking for loan to him, he gave me happiness to me and my family, i was in need of a loan of $250,000.00 to start my life all over as i am a single mother with 3 kids I met this honest and GOD fearing man loan lender that help me with a loan of $250,000.00 SG. Dollar, he is a GOD fearing man, if you are in need of loan and you will pay back the loan please contact him tell him that is Mrs Sharon, that refer you to him. contact Dr Purva Pius,via email:(urgentloan22@gmail.com) Thank you.

ReplyDeleteDo you need a genuine Loan to settle your bills and start up business? contact us now with your details to get a good

Loan at a low rate of 3% per Annual email us: namastecredit01@gmail.com

call or add us on what's app +13233665688

Please, do provide us with the Following information If interested

1) Full Name:.........

2) Gender:.........

3) Loan Amount Needed:.........

4) Loan Duration:.........

5) Country:.........

6) Home Address:.........

7) Mobile Number:.........

8)Monthly Income:.....................

9)Occupation:...........................

)Which site did you here about us.....................

Thanks and Best Regards.

email : namastecredit01@gmail.com

call or add us on what's app +13233665688

ReplyDeleteDo you need a genuine Loan to settle your bills and start up business? contact us now with your details to get a good

Loan at a low rate of 3% per Annual email us: namastecredit01@gmail.com

call or add us on what's app +13233665688

Please, do provide us with the Following information If interested

1) Full Name:.........

2) Gender:.........

3) Loan Amount Needed:.........

4) Loan Duration:.........

5) Country:.........

6) Home Address:.........

7) Mobile Number:.........

8)Monthly Income:.....................

9)Occupation:...........................

)Which site did you here about us.....................

Thanks and Best Regards.

email : namastecredit01@gmail.com

call or add us on what's app +13233665688