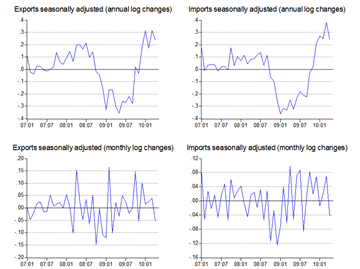

In my post last month on March trade, I said I thought that exports would slow down and return to the mean of what my models were predicting. A more normative explanation would be that the March numbers represented a catching up on production and clearing of accumulated finished inventory post-CNY. Either would do in explaining the April numbers (annual and monthly log changes, seasonally adjusted):

Not so good, but given the rationale I’ve thought up of (ex-post facto), not all too surprising either. It’s interesting to contrast this with the prevailing consensus view prior to the data release (38% growth in exports, 30% growth in imports), and analysts’ reactions afterwards. On a side note, I continue to be surprised that people think electrical and electronics exports are driving export growth (RM millions, seasonally adjusted):

Only half of the research houses expected April export growth to register below 30%, and none were even close in forecasting imports. I have to admit that I hesitated before writing that mean reversion line in last month’s post, simply because the consensus was running the other way and there’s also a very human tendency to extrapolate the future based on recent events.

Which brings us to the title of this post. The concept of rational expectations has taken a beating over the last couple of years, with the wide recognition that economic agents don’t always behave consistently or rationally. That applies to professional forecasters as much as it does market players. One of the problems with a non-model based approach is that there is a tendency for agents to display what’s called conditional expectations instead. This is actually also often used as a proxy for rational expectations, since with the former all you need is a knowledge of past events – “we expect this to happen because this happened” – which makes plugging data into models considerably easier (in fact, proving conditional expectations is all that’s required to prove weak form efficient markets).

Rational expectations of course, implies a more forward-looking view of events. But looking at the consensus view, more than a few were guilty of taking the March numbers and expecting that pace of growth to continue. You can see the same effect in research houses’ forecasts of trade and other variables during the recovery last year (leading up to the fourth quarter, they were highly pessimistic), and now the pendulum has gone too far the other way. For that matter, it’s highly unusual to find market forecasters who are willing to be publicly contrarian at any point in time, and you generally find forecasts tending to extrapolate off recent market trends. I’m as guilty of that as anyone is – it’s really hard to run against the herd.

There’s an excellent article in the The Economist last week along the same lines, though with respect to professional investors, not forecasters (I’m quoting in full, because free access to The Economist is time limited):

Who's the patsy? Even sophisticated investors have just been chasing returns

SMALL investors are often portrayed as the “dumb money” in markets, doomed to buy just before a crash and fatally drawn into buying fashionable sectors like technology funds in the late 1990s. But are wealthy and institutional investors really any better?

A new study* by researchers at the European School of Management and Technology examines how investors allocated money to hedge funds from 1994 to 2004. This process ought to be highly sophisticated. After all, hedge-fund investors tend to fall into three categories: rich individuals, who usually take advice from private banks; institutions, such as pension funds and endowments, which often employ investment consultants; and funds of funds, which market themselves on their expertise.

Hedge-fund selection is an extremely complex business. At the industry’s peak in 2007 there were almost 10,000 funds operating in a myriad of different styles. Potential clients need to examine the background of the managers, the level of safeguards (independent valuers, for example) and the likely return characteristics of each fund’s investment approach.

However, when the academics examined why investors ploughed money into different types of hedge fund, one reason stood out: recent performance. Funds that had performed well in the previous three quarters attracted significantly more money. Each 1% of extra performance attracted around $9m of new assets.

Such a return-chasing approach might be justified if investors were rightly anticipating that a short-term improvement in the returns of a particular hedge fund indicated a long-term shift in favour of its style. But the study finds that “there are no significant differences in subsequent performance between those styles favoured by investors and those less favoured.”

What explains this selection failure? It may be that hedge-fund styles are so opaque that investors are forced to rely simply on recent returns. But it may also be that investors are more careless about choosing hedge funds than they should be. Some professional investors put money with feeder funds linked to Bernie Madoff, for example, even though statistical analysis suggested his performance record was implausibly smooth.

Some of this faulty decision-making may also reflect the underlying rationale of hedge-fund investments. Take pension funds. For decades they used their bargaining power to force down the fees they paid to conventional, active fund managers. So it seems rather odd that they should have signed up for hedge funds which charge annual management fees of 2% plus 20% of any returns.

James Montier of GMO, an asset-management firm, argues that pension schemes have been pushed into the hedge-fund world by weak past (and likely future) returns from traditional asset classes. If valuations return to the mean, a benchmark portfolio split 60/40 between equities and government bonds will return just 4.5% annually over the next seven years. That is not enough to pay for pension promises, so funds decided to follow the example of Yale University, whose endowment diversified into hedge funds and private equity in the 1980s.

Alas, like the supposedly dumb small investor, the pension funds ended up chasing past performance. The flood of money into private equity caused more competition in the world of buy-outs, with the result that deals were done at higher valuations. Those higher valuations have duly led to lower returns.

Another rationale for the move into alternative assets (as hedge funds and private equity are known) is that returns are uncorrelated with those on other assets. But Mr Montier points out that the correlation of returns from different hedge-fund styles (which invest in a wide range of assets, from corporate bonds through to equities) has risen from around 0.3 in 1993 to 0.8 in 2009. Given that 1 would represent perfect correlation, that implies most hedge-fund styles are rising and falling in near-unison. As Mr Montier remarks: “It would appear as if all the hedge funds are doing exactly the same thing—riding momentum or selling volatility.”

It is all reminiscent of the “search for yield” in the past decade, which saw investors ignore risk as they piled into structured products linked to subprime mortgages. This chase for higher returns may not prove quite so disastrous. But it is more likely to reward hedge-fund managers than their clients.

Bottom line: forecasts are fun to do and read about, but always take them with a bag of salt, especially if you have money riding on the outcome.

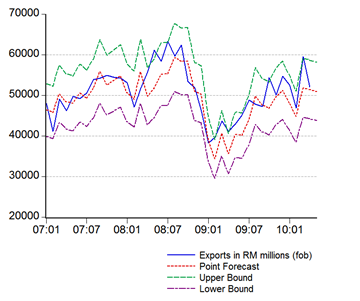

On to next month’s forecast (salt not included):

Seasonally adjusted model

Point forecast:RM53,536m, Range forecast:RM60,224m-46,847

Point forecast:RM50,892m, Range forecast:RM58,051m-43,734m

Note that both models are predicting exports to continue to contract marginally, given the fall in April imports. I’d make allowance for inventory build-up in prior months, so look for approximately flat to slightly positive m-o-m growth for May exports.

Technical Notes:

Preliminary April 2010 External Trade Report from the MATRADE

Thanks for the heads-up.

ReplyDeleteWhat were the factors moving the non-e&e exports, one wonders? ;P

http://is.gd/cFiix

One day someone may write a paper on the role of the Eywa in behavioral finance.