With all the recent movement in the Ringgit, it’s probably about time to look at where it really stands on an aggregate and disaggregated basis. I’m approaching this a little differently this time, and I’m going to focus on differences in the nominal and real indexes rather than the exchange rates themselves.

The real effective exchange rate (REER) suggests MYR weakness to be more apparent than real:

While both indexes have turned down, the nominal index (NEER) has been below the real index since about 2010, but the gap really widened this year:

It’s a highly unusual divergence historically, and the above suggests that the MYR’s value ought to be about 3% higher than it is now. That’s not exactly a big enough gap to say that it’s fundamentally out of line, but does underscore that the recent sell-down of the Ringgit is probably overdone and the underlying tendency for appreciation remains intact.

Some of this divergence can be traced to BNM replenishing its warchest (RM billions):

…but not fully, as reserve accumulation has been essentially zero for the past six months. So as far as this year is concerned, we’re looking squarely at the troubles in Europe driving up currency risk premiums, and prompting flight to safety (i.e. into the US dollar).

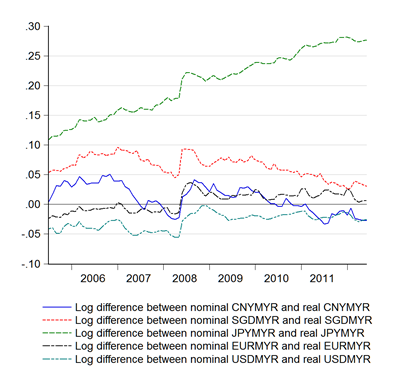

Of course, this says little about individual MYR exchange rates. Looking at the cross-rates for the top 5 Malaysian trade partners, we see a bit of a different story:

Undervaluation against USD and CNY somewhat offset overvaluation against SGD; EUR is more or less at parity, but JPY is the subject of some very obvious intervention on the part of the Bank of Japan. By rights, the JPY should be 25% stronger against the MYR and just about everybody else. That kind of currency adjustment probably wouldn’t be very good for Japan’s economy, but I digress.

If the weakness of the Ringgit isn’t really against the top5, it has to be against the smaller trading partners. So here’s a roundup of some of the culprits (log difference between nominal and real exchange rates):

The first batch above are all within about 11% or so – the biggest divergence is with the Korean Won while the smallest is against the Thai Baht. The bottom chart is a bit of a rogues gallery – the worst out of line is Vietnam at 67.9%, followed by Indonesia at 64.3%, with India (48%) and Philippines (32.5%) rounding up the lot. This is hardly just a phenomenon against the MYR alone – the relative values of the MYR against major currencies suggests something seriously out of whack with these currencies.

The main cause is of course individual country inflation records, which by construction helps drive movements in real exchange rates. There’s no doubt that the bottom batch have considerably worse inflation records – the divergences recorded here shows their currencies haven’t fallen enough in nominal terms to compensate.

Given that for the most part these four countries have also been accumulating reserves (and consequently putting downward pressure on their own currencies), it’s thus not from a lack of trying. India and Indonesia of course have been a focus for foreign portfolio and direct investors, which is also somewhat true of the other two. These inflows, as well as capital controls and underdeveloped financial markets, have helped maintain the level of their exchange rates even as the fundamentals are screaming “sell”.

Another aspect of this is the Penn effect, where higher income countries tend to have stronger exchange rates. Looking at the ordering of countries above, with the exception of China there’s a rough symmetry between income levels and exchange rate valuation. I’ll return to that issue in a future post. One other factor to look at would be commodity prices – again something I’ll try and look into for a future post.

Bottom line: don’t sell the Ringgit short. If the economy continues to grow and markets calm down a little, you should see its value recover. Personally, I still think the medium term impetus towards appreciation is still intact.

Interesting concept...

ReplyDeleteThe only problem is REER covers pnly the trading partners... How about other factors such as political intervention, mismanagement, etc...

Sorry, what has politics got to do with the exchange rate? Since the float in July 2005, BNM's forex policy is hands off except during times of volatility.

ReplyDelete