It’s been nearly a year since Malaysia’s minimum wage law came into effect. Although enforcement has been held off until next year from the loads of companies applying for a postponement, most have already complied.

So here’s my crack at trying to figure out what the minimum wage’s impact on Malaysian employment, unemployment and incomes. Most of this material is taken from a presentation I gave at UTAR earlier this week.

There are two basic arguments on the impact of a minimum wage on employment:

- Higher incomes draws greater labour supply which leads to greater consumption, which in turn leads to higher employment; but...

- Higher wage costs means slower job creation/hiring, or higher unemployment

What we really want is a long term assessment, but since we’re less than a year into this, that’s obviously out of the question. Moreover, public data on the data we’re interested in is short-spanned and at an aggregated level only. Monthly wage data has only been regularly collected for manufacturing, and only since 2009; the monthly employment and unemployment from DOS is of the same vintage. There are no Malaysian time series for overall wages.

We also have some identification problems as many factors influence wages, employment and growth. Any attempt at teasing out the impact of the minimum wage alone thus has to be treated with caution.

The results

To save the less econometric minded from boredom, here’s my results:

- Both overall employment and unemployment appear to have been affected, though unemployment more strongly than employment;

- Overall employment was raised about 5% (4.8% without seasonal dummies, 5.3% with), or about 640k jobs;

- Overall unemployment was raised by around 8.1%-8.8%, or about 36k-39k jobs;

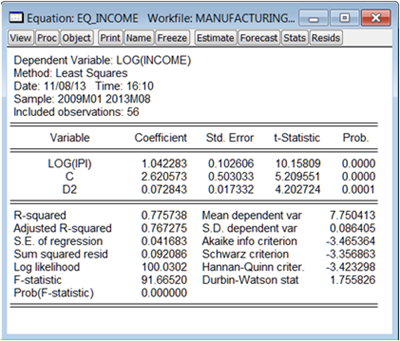

- Manufacturing shows a different response – employment did not increase, but average incomes did;

- I suspect this may be due to high propensity to export (demand is externally derived), which means employment will not vary with domestic economic activity (mis-specified model and/or omitted variable bias)

- Average incomes in the sector were raised by 7.3% (w/o seasonal dummies) or 5.6% (with seasonal dummies)

In short, the minimum wage appears to have had the desired effect, at least in raising incomes over the short run.

As a side effect, unemployment was also raised but offset by greater employment. How do you get an increase in both at the same time? Basically, higher wages at the low end have drawn people who are out of work, or in the informal economy, into the formal economy. Technically, we got a higher labour force participation rate.

The boring bits – A look at the aggregated data

Basically, I applied two very simple models to test the effects of the minimum wage:

EMP = f(Y) + D and

UNEMP = f(Y) + D

Where:

EMP = employment

UNEMP = unemployment

Y = economic activity (proxied by IPI)

D = dummy variable for imposition of minimum wage

Why IPI and not GDP? Because IPI is available as a monthly series, and GDP is only quarterly. Plus, because IPI is a pretty good predictor of GDP.

We also need to account for structural changes in labour force i.e. registration exercise of illegal foreign workers circa Dec 2010-Jan 2011, which adds one more dummy variable to the model(s) specs.

Note: By rights, I should include seasonal dummies as well, but as the results for these were virtually identical with the unadjusted models, I’m not going to bother reporting them except where necessary (despite some interesting seasonal effects).

I’m also going to test the changes in the labour force participation rate, but this will be a simple test of a change in the intercept.

Employment model:

This one’s pretty unambiguous – there was a statistically significant increase in employment at the same time the minimum wage came into effect. This doesn’t change if we add seasonal dummies to the model.

Unemployment model:

This one’s a little harder, because the model is not a good fit for the data. Nevertheless, there is a statistically significant positive change in unemployment occurring at the same time as minimum wage coming into force.

Labour Force model:

I really ought to specify this model to test the change in slope, not intercept, but for my purposes this does the trick just as well. In essence, the LFPR has been generally increasing over the span of the data, but is trend stationary. That changed in about March 2013, when it started leaping up quite remarkably. While the causality might be iffy, I can’t think of anything else that could possibly be a factor – certainly GE13 shouldn’t qualify – and it fits the minimum wage narrative pretty well.

In depth with the manufacturing sector

I’ll be using the same approach here, although we can’t test for manufacturing “unemployment” because there’s no such thing. So instead, I tested the impact on incomes (average wages per worker).

Again two simple models:

EMP = f(Y) + D and

INC = f(Y) + D

Where INC = average income per worker

Manufacturing employment:

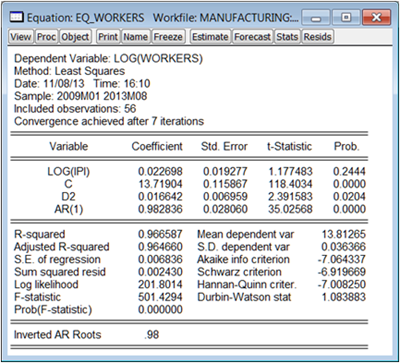

I had to use an AR(1) term here because of serially correlated errors, but while the model is a good fit, IPI is not a significant explanatory variable for manufacturing employment. I can think of a number of reasons for this, mainly stemming from high foreign ownership and an export-oriented approach – domestic production wouldn’t be a good indicator for foreign demand, or take into account the globalised supply chain of which Malaysia is a part.

However, the dummy for the minimum wage is statistically significant and positive, indicating that it did raise employment in the manufacturing sector. As it turns out though, this wasn’t really the case as explained below.

Manufacturing employment with seasonal effects:

[Note: the residual chart is virtually identical to the model without seasonal dummies]

Adding seasonal dummies to the model above, the minimum wage dummy turned out not to be significant at all. In the result above, the dummy really was just capturing a seasonal effect – hiring is generally much higher in January, which coincided with the implementation of the minimum wage. In fact, hiring in the manufacturing sector is also significantly higher in November and December as well.

But I can only confirm this for the manufacturing sector alone, as the models for the aggregate employment and unemployment data do not show the same seasonal effects i.e. my results for aggregate employment and unemployment remain valid.

Manufacturing wages:

There is no such ambiguity with the income data – the average wage did rise with the minimum wage.

Final Thots

There are a whole bunch of caveats to go with this sort of analysis:

- Short sample span, and only in expansion phase of current business cycle; dynamics are not tested either (i.e. there should be a lag structure to employer/employee responses to MW)

- MW should affect only labour market for workers with wages around the MW level (short term), and not total employment. Aggregate numbers may hide the truth

- Presence of large illegal foreign labour force substantially masks impact of MW (variability of official employment/unemployment stats may be muted by unseen workforce)

- Low wage workers might be concentrated in certain sub-sectors of the economy, but lack of data to establish for certain

- New research paper suggests employment impact is mainly on the margin i.e. new job creation for smaller companies, rather than employment in the economy as a whole

- The literature suggests a nonlinear threshold response of employment to minimum wage levels – Malaysian MW might be too low to show significant unemployment effects

Those are the ones I can think of offhand, and there are bound to be more.

So take this for what it’s worth, a highly preliminary look at the economic impact of the minimum wage. A more concrete assessment will need to wait a few years, and hopefully with much better data than I have at hand.

Technical Notes:

Data on employment, unemployment, labour force participation rate, and the Industrial Production Index (IPI) from the Department of Statistics

Warrior,

ReplyDeleteI think either the vodka's gone to your head, or you need to go back to school :D

1. Nowhere in the analysis is there anything about growth of employment or unemployment. The way the models are constructed, I'm testing for one time effects only.

2. The increase in percentage terms can be misleading, which is why I quoted actual numbers (640k vs 36k-39k). And this is only evaluated at a single point in time, i.e. January 2013.

3. An increase/decrease in either or both employment and unemployment says nothing about the participation rate.

4. An increase (or decrease) in the working age population again says nothing about the LFPR. The LFPR is a ratio of those in employment or seeking work, relative to the population of working age. It's not an absolute number. Assuming no job growth, an increase in the base reduces, not increases the LFPR.

5. The LFPR has been generally increasing since 2008:

http://www.statistics.gov.my/portal/download_Economics/files/DATA_SERIES/SURVEY10/PDF/TABLE1.pdf

There's your response to the higher cost of living. This is consistent with the US experience (change the graph input to 1948-2013 to see what I mean):

http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS11300000

The US LFPR rose in response to the inflation of the 1970s from about 59.8% in June 1971 to 64.3% in May 1981. Malaysia's LFPR has risen from 62.6% in 2008 to 65% by the end of 2012 - the rate of increase is almost identical.

However, within 2013 alone, the number has risen from 65% to nearly 70% i.e. the total US labour response for an entire decade, happening in a matter of 9 months. The US "surge" you were talking about in the other post (1977-1978), raised the US LFPR by only 1% a year. The 2013 Malaysian "surge" is of a wholly different order of magnitude, and needs a different explanation.

The increase in the Malaysian cost of living generally dates from 2007-2008, but has decelerated in the last year. If you were to try to use this to statistically test against the 2013 increase in the LFPR, I'm afraid it would fail. Demographic changes could also be used to explain the pre-2013 increase in the LFPR - but again, the 2013 increase is a completely different animal.

Hi Hisham,

ReplyDeleteAs always your post is thought inspiring. So, what makes me think twice is of course the statistically significant positive employment effect of MW. Even if we are ready to believe that MW has no discernible negative employment effect as employers respond by enhancing labour productivity that has maintained effective cost, or that MW has positive employment effect, thanks to the consequential wealth effect that stimulates aggregate demand, 7 months (as your dataset ends at July 2013) is simply too short for such productivity-enhancing effect as well as the wealth effect to materialise.

So, following your spirit, I also regress the impact of MW. I create a dummy for MW (D_MW; 2013Q1=1) and another for illegal migrant labour registration (D_IL; 2011Q1=1), and use industrial production index (LIPI) as you did as proxy for economic activity. But I didn't use employment and unemployment as proxies for labour market, as I have doubt on the immediate effect of MW on it. Instead, I suspect the immediate negative effect of MW falls on the firms' willingness to create new jobs. So, I use the data on the number of job vacancies created (LV). To inspect on the MW effect on the labour market tightness (as higher wage attracts more job seekers while distorting firms' incentives to offer new jobs), I compute market tightness indicator (theta) as the ratio between active job seekers and number of job vacancies. The quarterly data ranges from 2007Q1 to 2013Q3 sourced from BNM. Below shows the estimates:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dependent Variable: LV

Method: Least Squares

Date: 11/30/13 Time: 14:58

Sample (adjusted): 2007Q2 2013Q3

Included observations: 26 after adjustments

Newey-West HAC Standard Errors & Covariance (lag truncation=2)

Variable Coefficient Std. Error Prob.

LV(-1) 0.6744 0.1656 0.0005

LIPI 0.8917 0.4511 0.0607

D_MW -0.2717 0.0508 0.0000

D_IL 0.3915 0.0517 0.0000

R-squared 0.538911 Durbin-Watson stat 2.530136

Adjusted R-squared 0.476035

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dependent Variable: THETA

Method: Least Squares

Date: 11/30/13 Time: 15:01

Sample (adjusted): 2007Q2 2013Q3

Included observations: 26 after adjustments

Newey-West HAC Standard Errors & Covariance (lag truncation=2)

Variable Coefficient Std. Error Prob.

THETA(-1) 0.4825 0.2459 0.0619

LIPI 0.0861 0.0412 0.0477

D_MW 0.2806 0.0306 0.0000

R-squared 0.294787 Adjusted R-squared 0.233464

Durbin-Watson stat 2.280503

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All the estimates pass the diagnostic checking: no hetero and model misspecification, and residuals are normal and serially uncorrelated. The results are not optimistic: MW implementation has caused the number of job vacancies to fall, and the labour market becomes tighter. Not shown here is that when MW enters the equation as an interactive term with IPI, MW statistical significantly reduces the responsiveness of job vacancies toward industrial expansion. In other words, job creation power of industrial expansion may have been compromised.

Anyhow, as you have mentioned, which I strongly, it is too early to call for a concrete assessment. But the preliminary findings may not be as optimistic as you have found.

Maybe you want to see this interesting paper, Chin Yoong. It affirms MW's negative impact on job creation:

Deletehttp://econweb.tamu.edu/jmeer/Meer_West_Minimum_Wage.pdf

Maybe, you econs guys should also test whether MW has an augmented effect on job destruction in the Malaysian context.

Finally, it should be noted while lower job creation is not immediately visible in employment rates (per the above paper), nevertheless:

"The effective elasticity over the typical relevant time frame is -0.1204.18. That is, each ten percent increase in a state’s real minimum wage, relative to its regional neighbors, causes a 1.2 percent reduction in total employment relative to the counterfactual by the end of five years"

Warrior 231

Hi Chin Yoong,

DeleteYup, as I mentioned in the notes, I didn't model dynamics in any of the models, so the causal transmission from MW to employment and unemployment is more than a little theoretically iffy. Yet I'm still taken with the one-time statistically significant coefficients for both during the MW implementation month. When I first did the analysis, that result completely floored me, which is why I used it in the presentation. I didn't expect it at all.

I think I also mentioned in the caveats that job creation is likely to be the main victim of MW (point 5 in the last list in the post). The specific paper I'm referring to is this one:

http://nber.org/papers/w19262

If I can offer one criticism, THETA as a ratio is by construction stationary (I(0)), so ideally you should be regressing against dlog(IPI) and not log(IPI) directly.

Dude …I am as sober as can be even when drowning in vodka,…….….hohohoho. And school is everyday, man….as long as I live….hahahahaaha (wink wink).

ReplyDeleteLeaving aside my abject humiliation : C by an expert which should be a cautionary tale to all layman expert wannabes……… hahahaha, purveyors of the Minimum Wage panacea should pause and think about the following:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/douglas-holtzeakin/the-mythology-of-the-mini_b_4338234.html

In fact, a warning as to the limitations of MW is already cited in this internal paper (citations disallowed):

http://liewchintong.com/lctwp/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Minimum-Wage-Report.pdf

Finally, some desultory observations from a simple visual analysis of the August 2013 figures:

a. There has been a 5 point increase in female participation since 2010, a consistent pattern that mimics the 70s female surge in the US LFPR:

http://www.miti.gov.my/storage/documents/994/com.tms.cms.document.Document_6c9e8a29-c0a8156f-522a533e-a1468753/1/MITI%20Weekly%20Bulletin%20Volume%20258%20-%2030%20September%202013.pdf

b. A total of roughly 700k shuffled from the outside labour force cohort into the formal labour force zone from January to September 2013 and the bulk of this could have come from those previously in education or training as is common elsewhere:

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Labour_market_participation_by_sex_and_age

c.The illegal worker whitening program that ended on August 31 accounted for the substantial flow from the informal labour sector into formal sector. If one studies the monthly data one will notice, the surge proper gained traction in June 2013 (Q3) and extends to August 2013 (note Jan-May 2013 rehashes the traditional yo-yo pattern of yore if one looks closely at page 3 with no significant divergence from the LFPR trend line):

http://www.statistics.gov.my/portal/images/stories/files/LatestReleases/employment/2013/Labour_Force_Indicator_Malaysia_Aug_2013BM.pdf

(see page 3; 2013)

which tallies precisely with the tail end of the whitening processs:

http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/6p-whitening-programme-will-not-be-extended.

In fact, the blogmaster himself somewhat obliquely acknowledges this in his post above:

“We also need to account for structural changes in labour force i.e. registration exercise of illegal foreign workers circa Dec 2010-Jan 2011”

The MW did contribute to the surge as indicated by the model but presumably less significantly,and most likely mildly, than is conjectured. In any case, the above evidence (a-c) clearly attests that MW is definitely not the prime cause of the surge by any stretch of the data or…..er ……dilution of the vodka.

: D

To conclude, a combination of factors i.e, demographic, administrative (6P exercise) account for the surge and to aver otherwise that MW was the sole cause based on iffy outcomes would be to confer an essentially bad policy decision (introduction of MW), an undeserved accolade.

Warrior 231

Warrior,

DeleteI'm well aware of the theoretical limitations of MW as a policy - that's why I wanted to try and objectively estimate its effects, sans ideological posturing. Evidence, evidence, evidence...otherwise we're all talking hot air.

1. The increase in the female participation rate as well as reduction in the dependency ratio is probably behind the steady increase in the LFPR over the past five years. But unless you're going to argue that nearly half a million extra females and students suddenly decided leave home life or drop out of school to join the job market in a matter of months this year (over and above trend rates), these factors do not explain the surge. That's why I used a trend regressor in the blog post.

2. Registration of illegal workers should symmetrically increase both the labour force and the working age population and there should be little to no change in LFPR. In fact, that's precisely what happened to the LFPR during the last exercise in 2010 i.e. almost nothing.

Between December 2010 and January 2011, the working age population increased 4.0% over the month while the labour force increased 4.3%, with the result that the LFPR rose from 64.5 to 64.7, which is pretty much the same seasonal increase seen every year.

In this year's surge however, there has been little change in the working age population during the year.

3. Movement of workers from the informal sector to the formal sector is certainly a candidate for explaining the surge - but then you're left with trying to explain why. And the only structural change I can think of to explain this deviation from trend (note: not level), is the MW.

One last note: it's possible that the increase in the LFPR could be caused by a statistical quirk in the way DOS is estimating the numbers, or by improved sampling. But there's no sign of this in the notes to the labour force reports.

Yeah agreed, this should be free of ideological baggage, democrazy or not withstanding. Evidence, evidence everywhere but not a sliver of proof to exorcise a ghoul, is it??......hahahahahaha (hic). Seriously speaking a lot of proofs are staring at us stark naked in embarrassment ala the emperor ; D. If only we all be little boys and holler to the emperor to go stuff his shrivelled pecker into something instead of leaving the wee lil pee wee dangling in public for them juicer boys to........ (Ok enuff, warrior or you get banned. : - { (sad....this so hypocritical public aversion to all things ...er.....pubic)

DeleteOk, the summation regarding the foreign worker registration and the LFPR figures does not hold up when one looks at the 2010 data :

November 2010 = 62.3

December 2010 = 65.0

Source: Page 3

http://www.statistics.gov.my/portal/images/stories/files/LatestReleases/employment/Labour_Force_Indicator_Malaysia_Jan_2012BI.pdf

Given the above surge of 2.7 on 2010 was within 1 month compared to the 2013 surge of 3.1 which was spread over 3 months , it is clear that such registration exercises can precipitate dramatic changes to the LFPR. Moreover, a cursory analysis of the 2010 data will also reveal that the informal labour sector lost roughly 500k individuals while the formal labour sector gained an identical 500k in that December period, so we can safely assume where those people zombie-registered into........hahahaaha. Move to Jan 2011, the figures drop slightly but still remain a point above Feb 2011. Point is there was no bloating of the labour force only shuffling from the informal to the formal.

Similar monthly surges are also discernible albeit on a smaller scale for Feb-March and Sept-Oct 2010 as well as June-July 2011, all close or thereabouts to illegal workers whitening exercises.

2013- It should also be noted that the 1.2 increase for female participation in the LFPR as quoted from the MITI link was for the January to June 2013 period only and doesn’t include the June to August period .

In fact, the quantum in the formal sector surged by 1.8% from June to August 2013 alone.

Thus, it would be fair to make a case that a perfect storm of women + foreign workers + students/other (entering the labour mart in anticipation of jobs given the perception of a growing economy) contributed substantially to the LFPR surge in June-August 2013. And pray, what shalt thy LFPR do but jump like a frazzled kitty whence swiped by a tempest of such biblical bombast...er...proportions.

In any case, the MW while suggesting a role, could not have been a major factor or else we could have seen a surge as early as January(Q1) onwards ( rather we see a fluctuating graph not diverging much from the underlying LFPR trend line in Q1 and much of Q2). Instead, we get a surge at the tailend of Q2 (June onwards) dovetailing another whitening exercise.

As to why for the late surge, well, Malaysian employers being Malaysians are notoriously tardy when coming to registering their illegal workers let alone dealing with the bureaucracy for pretty much everything else (traffic summons spring to mind, mine included....hahahahaha). And even more so when they have seen too many policy flip-flops and extensions in enforcement deadlines that they took another extension from September 1 for granted and when it didn’t come....you and the readers know the rest.

I would love to see the registration figures for illegal FWs that will surely back up this narrative but I sure aint gonna gnaw my fingernails down to the bone, waiting....hahahahahahaa.

Time for a bout of vodka and a dash of flippancy......hahahaha . Ciao (hic).

Warrior 231

Warrior,

DeleteNow you're grasping at straws. The increase in Nov-Dec 2010 doesn't take the LFPR out of its normal range - indeed, if you look just a little further back, you can see almost the same pattern (sharp dip then sharp increase) happening two months earlier. Neither was this a consistent monthly increase like we have with the 2013 surge.

So what happened? Did all these illegal-turned-legal workers register, then de-register, then re-register again?

Also did you notice that the working age population group actually fell between Nov and Dec? How could that be mathematically possible if the increase in the LFPR was due to the illegal worker registration exercise, which would raise both the formal labour force and the working population age group? Formerly illegal alien workers wouldn't be counted under either - including them would raise both.

Also note that a similar statisical pattern happened at the end of 2011, sans illegal worker registration exercise.

Correction

ReplyDelete........ in June 2013 (Q3)

should read

in June- August 2013 (tail-end of Q2, and first 2 months of Q3)

Warrior 231

Hi Hisham,

ReplyDeleteI overlooked your point 5 in the list. But my rough evidence in a way confirms your conjecture. Anyhow, this is really a rough fact check as I took only 15 minutes from data collection to estimation. Just wanna see the variety of effects of MW on labour market. It will be interesting to see how fast the labour market, either in terms of employment/unemployment or job creation, adjusts to the MW shock by estimating the correction term.

I did take a quick check on the unit root for theta. The null of unit root is not rejected at 5% significance level with intercept.

One puzzle I have in mind is that based on the 2012 household survey, only 5% of households earn income below RM1000. Inferring from this stat, MW shall have no discernible effect on employment, neither positive nor negative, as majority of domestic labour forces already earn more than the MW. But reading from BNM report, as well as other investment houses analysis, about 27% of labour force will be affected, which translates into approximately 18.5% of total households , assuming that a household comprises 4.6 persons and 65% labour participation rate. This is a huge proportion. With 18.5%, MW will improve households' living significantly on the one hand, but certainly will make businesses and job creations tougher on the other hand.

Do I mis-read any statistics here? How can the estimates on the number of households affected be so different from different sources? We not even yet talk about estimation but the raw data.

Chin Yoong,

DeleteYou're assuming a nuclear family, but about half the households don't fall neatly within that category. For example, many foreign workers live effectively in dorms of up to 20 in a "household". It's a highly skewed, fat-tailed distribution.