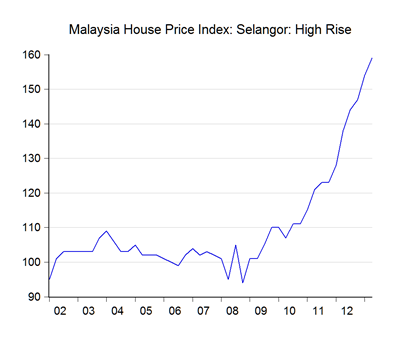

How can you tell you’re in an asset bubble? How can anyone not look at this graph and say that we’re not (index numbers; 2000=100):

But I couldn’t and still can’t, at least not by any objective measure. Here’s a look at why.

Consider the overall Malaysian House Price Index (MHPI index numbers; 2000=100):

If I were to draw a trend line for the MHPI for the period 2002-2008, it would look something like this:

Anybody seeing this would declare, without reservations, that we have a housing bubble. The price differential between actual prices and my trend line is currently about 20% (log difference):

But if I were to model it out (using working population and GDP as explanatory variables):

The line fits the actual increase in prices much more closely, and our “bubble” becomes more of a pimple (log difference):

From 20%, the differential is now just 7.5%. It’s a little higher than it should be, but not “bubbly”. Of course, the overall MHPI aggregates prices across a whole range of markets – house prices in Johore for instance are only 30% above 2000 levels, compared to 128% for KL, 106% for Penang, and 81% for Selangor. And even within states, there are significant differences between districts and by property type (e.g. high rises in KL are up 92%, but bungalows are up 180%).

Nevertheless, two different approaches, two substantially different conclusions. Which one’s right? I don’t know; I can argue for and against both.

The trend line approach provides an immediate sense of the increase in house prices, and one that fits well with the experience of the man on the street. But it also implicitly assumes that the historical movement of prices pre-2009 was “fundamentally” correct, which is an untested and potentially unwarranted assumption, especially given price movements before 2000 – note the steeper slope of the index from 1990-1997 (index numbers; 2000=100):

The econometric model provides a closer fit between explanatory data and actual realisation – but that’s potentially a weakness in itself, as it presumes that the model is correctly specified and because OLS estimation by construction minimises the variance. Most of the models for housing demand used in the literature start from microeconomic foundations and build from there, but the same criticism applies – a closely fit model doesn’t give you a full sense of fundamental misalignments.

[For statistics wonks, the model I’m using for the charts above isn’t correctly specified, as the sign for income is wrong. Adding a AR(1) variable corrects the problem (essentially fixing autocorrelated error terms), but as ARIMA models tend to give very close fits, any price variance from “fundamentals” are even further minimised. Check the end of the post for estimation results]

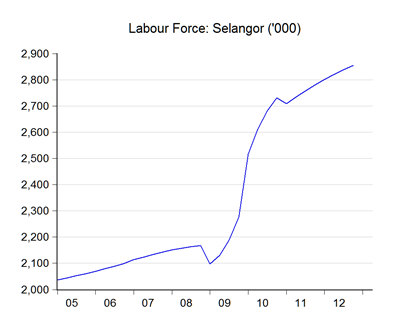

I could add further arguments: the pattern of house price increases mirrors that of internal migration. Selangor for instance saw a huge influx of workers after 2009 (quadratic-averaged interpolation; ‘000):

Population pressure explains part of the increase in house prices in particular areas.

Another part of the puzzle is this one:

Developers are completing just between 20k-40k homes a quarter over the past three years – that’s half to one third down from the level 10 years ago.

So we have a confluence of “fundamental reasons” that could be driving house price increases, at least within certain segments and certain locations. Higher than normal demand coupled with inadequate supply results in higher prices to ration the existing supply relative to demand. It’s not just a credit-driven, speculative frenzy pushing prices up.

So, what about credit? Mortgage loan growth is rising, but well off previous peaks (log annual changes):

The absolute levels are certainly increasing however (RM millions):

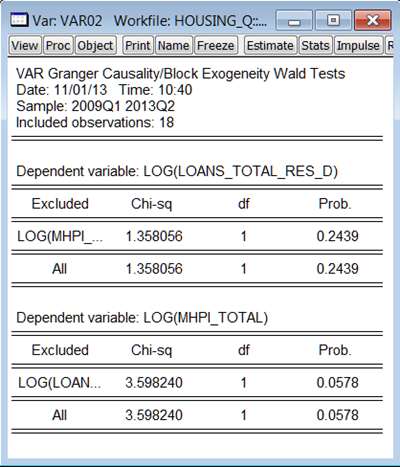

Just to be sure, I put prices and changes in mortgage loans outstanding in a VAR, concentrating on the post-recession period of 2009-2013 (again, see results at the end of the post). The estimates show that house prices and mortgage loans granted are certainly related, but causality tests are mixed depending on which sample period is tested. Before the recession, house prices were leading (granger-causing) mortgage loans; after the recession, loans were granger causing prices but the confidence level is smaller than I’d like to see (cannot reject null hypothesis at 95%, but rejects null at 90%). So there’s certainly an element of expansive credit driving up house prices after the last few years, but its not wholly the answer.

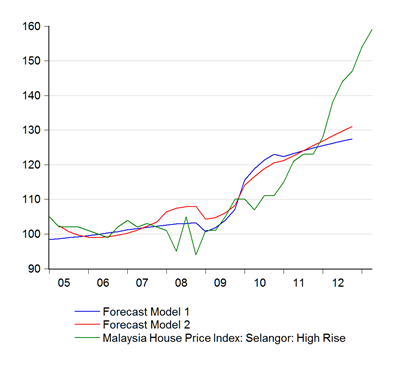

Having said that, let’s relook at the first chart above on prices of high rises in Selangor:

That’s my two best guesses at forecasting where prices should be – at the end of 2012, market prices were somewhere between 15%-10% too high. If we extrapolate that forward into 2013, the price differential is probably double that.

The same criticisms apply of course – high rise prices were almost flat from 2002-2008, which is highly unusual for property. We could thus be seeing a price catch-up in a sense (e.g. the KL example I quoted above). And neither can I tell if I’m over- or under-fitting the models to the data, or completely misspecifying them. The two model estimates suggest neither income nor population growth are good explanatory variables – which certainly suggests a bubble. Price rises are essentially feeding on themselves.

In simple English, estimating a statistical relationship from historical data makes the implicit assumption that there is a relationship between fundamentals and prices, and that this relationship is stable across time. But by definition, asset bubbles occur when prices deviate substantially from those suggested by fundamentals. If you fit a model to historical data that includes bubble periods, your estimates will be totally wrong and will tell you you are not in a bubble even if you actually are.

To make a long story short, you can’t identify a bubble through statistical means when its actually happening. It only becomes clear after the fact, when of course its far too late.

So the bottom line is: I think we have a property bubble, but I also think it’s not too frothy. And I can’t substantiate either of those two opinions.

Technical Notes:

- MHPI data from the National Property Information Centre

- Population and labour force data from the Department of Statistics

- GDP data from Bank Negara Malaysia

Model estimates:

Trend OLS:

Uncorrected MHPI OLS [note negative sign on RGDP. Yes, I know I should use nominal per capita income, but the results are functionally the same. The point estimates are very close, although the standard errors are a little smaller]:

MHPI ARIMA [as above, point estimates for RGDP and NGDP per capita are close, though this time standard errors using NGDP per capita are larger]:

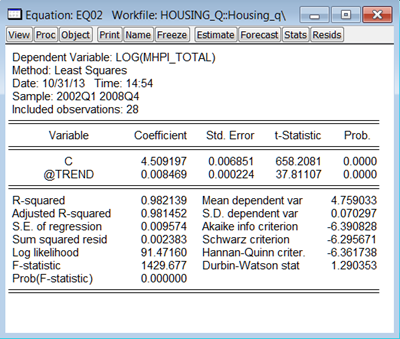

MHPI Selangor High Rise Model 1 [note: per capita NGDP is not statistically significant]:

MHPI Selangor High Rise Model 2 [note: neither income nor labour force numbers are statistically significant]:

VAR for MHPI and Mortgage loans [lag length of 1 quarter selected based on information criteria]:

Hishamh,

ReplyDeleteVery illustrative data indeed. I think this is great introductory work for those who wish to pursue this research further. Though, I think looking at mortgage lending alone may not be painting complete picture of a bubble. I understand that you were making a point about a credit-driven bubble.

But I think that intuitively, including total household debt is a better warning sign of whether a bubble is about to burst or not. After all, we have to repay all our loans, not just the mortgage. And once the defaults kick in (it may not be in the mortgage sector), the whole financial system could suffer a shock.

Also, perhaps a more illustrative comparison could be to control for loan growth and the income growth of the middle income group (instead of GDP?). My theory is that this would constitute the bulk of new home buyers and if the growth in house prices continue to outpace that of income levels, sooner or later, there will be a bubble.

I am also leaning towards your findings that we may not be in a bubble yet. But the warning signs are definitely there. In relation to your previous posts about RPGT, I also think a lot more needs to be done to curb speculative demand.

On a side note, I also believe that our current property market is broken. Property developers are given the green light to pretty much build whatever they like, wherever they like. I think that supply side measures like planning and feasibility studies are just as important as demand management in order to provide a conducive environment for sustained growth in Klang Valley.

@Shihong

DeleteOne of the peculiarities of Malaysia's household debt is that its sharply divided between lower income (high gearing but low exposure) and higher income (low gearing but high exposure) households. The risk is all at the lower end, but these aren't really the ones involved in the property market. As everyone points out, they can't afford it. So the risk of financial fallout is somewhat less than the total household debt would indicate.

Second, most of the recent growth in household debt has been through non-bank channels. Any trouble in that sector has limited implications for the broader financial system i.e. the possibility of contagion, and thus impact on the broader economy, because they have very limited linkages to the interbank system. I'd also add that the seeming growth in household debt is partially a reflection of slowing nominal GDP growth, and not absolute debt levels.

Third, based on the Household Income Survey, income growth is about the same for all income levels, which means GDP is still a reasonable proxy.

On your last point - I fully agree. The government all this while has been depending on private developers to provide for Malaysia's housing needs, but at the same time dictating quotas on low-cost and medium cost housing. However, these can be evaded by simply building more limited developments. The end result is that developers have mostly concentrated on small, high margin developments to maximise their profits, leaving out a whole section of the market being nearly neglected. And they're making that same mistake again, based on the latest reports.

Hishamh,

DeleteThanks for prompt and insightful reply! The reason I brought up household debt is based on anecdotal evidence. I have come across more and more couples who recently signed joint loans to purchase houses. These are 25-35 year-olds who earn quite a decent living but not enough to purchase a home individually. Obviously I don't have the data on this particular group, but I just wanted to point out the motivation for raising the point earlier.

Regarding the point on the supply side, the implications of proper town planning goes far beyond the issue of affordability. As KL becomes more and more dense, planning becomes even more crucial to minimize the traffic problem. It is not just traffic jam, but parking has also become a tremendous issue. I find it hard to blame the people who double/triple park because there really is no other option due to insufficient parking. I attribute this to poor town planning. It is not just landed properties, but many apartments/condos in the Klang Valley have insufficient parking.

Shihong,

DeleteAgreed, though I don't think it's necessarily all due to poor planning (though I'll echo the thought about apts/condos). It's really hard/impossible to plan for something like the big jump.in population like Selangor has seen (see the chart in the blog post). That's a 25% increase in the working population in just two years.

The word Sustainability have most often been neglected by both the authorities and private sector alike. More like Kiasu is the way things get done. The maths and sciences of sustainable development only emerges after a crash. The public based their perception on a bubble when prices goes far beyond their means...

ReplyDeleteHishamh,

ReplyDeleteCould you please elaborate a bit on the non-banking sector that households are borrowing from (Loan shark?)

Zuo De

Hisham, nice post! Thank you.

ReplyDeleteZuo De,

The non-banking sector doesn't mean loan shark, there are companies which are allowed to undertake financing activities without a banking license, i.e. NBFI like MBSB/RCE Capital, credit providers like Courts Mammoth/Aeon Credit or cooperatives like Angkasa for civil servants.

Thanks Steve.

DeleteThis research is great and insightful. Many thanks.

ReplyDeleteWe are living in a quasi bubble, dude although the model results might be foggy, given the contrasting signals generated. In my 46 years of existence, I have seen the selfsame tell tale signs twice once preceding 1996, the other now. It also explains your personal flummox over why income inequality increased between the Bumis and the Chingkies since circa 2009. But I don’t want to get into some race bashing fest given that I am on a self-imposed abstinence right now on that count, a personal detoxification if you understand….hahahahahaa, wink wink. Besides it wouldn’t change or correct any screwed up perceptions (not yours) anyway ; P

ReplyDeleteMy personal take is that when the economy goes into a deep funk, exports and by extension incomes get screwed, the eventual defaults will spawn a systemic bank collapse although I wager some banks will survive given their relative positions of strength. But predicting a collapse is subject to many variables both internal and external. For one Najib’s 2015 GST is a gambit to drive 2014 growth via consumption on the back of the misplaced inflation expectations attached with GST. So my wager is on 2015, and I am betting my house on that one……; 0

By the way, below are some primers for those interested in divining asset bubbles. Bernanke is right about poor underwriting standards, poor risk management, regulatory laxity and that is especially the case in Malaysia particularly amongst NFIs. This one especially rings a bell given similar harebrained schemes were dangled before the Malaysian public:

“I noted earlier that the most important source of lower initial monthly payments, which allowed more people to enter the housing market and bid for properties, was not the general level of short-term interest rates, but the increasing use of more exotic types of mortgages and the associated decline of underwriting standards.” (Bernanke in link below)

I doubt monetary policy this late in the day will alleviate the issue as it is, like the GST, too late in the day as the horse that bolted the KL stables might be in Timbuktu already : D

Anyway, for those interested in divining about blowing bubbles, like all good West Hammers like to do, here are some Wrigley’s to chew on:

http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2011/html/sp110503.en.html

http://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/how-to-spot-a-housing-bubble-20130925-2ue44.html

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20100103a.htm

Though the best I have ever had bubbling in my mouth was Stride with Orbit in close tow:

http://www.stridegum.com/

Have fun

Warrior 231

Starting from the base assumptions that real estate is local, that neither Penang nor Johor Bahru have had significant population expansions (unlike KV), would you say that Penang and Johor Bahru are likely to be in a bubble, and that their bubbles are substantially frothier than KV?

ReplyDeleteI think that it has been very widely reported that rental yields on property in Penang is so low that its market is largely speculative. Yet, this has been the case for quite a long while.

@anon 9.49

DeleteFrom the data, both Johor and Penang saw significant increases in labour inflows in 2010 (7.7% and 7.4%), so some element of the demand side is certainly there as well, even if neither saw as dramatic increase as Selangor did (21.2%).

Also, house prices in Johore were seriously depressed after 1997-98, so there is some element of catch-up here. Penang on the other hand suffers from far more limited land space (the island isn't growing as far as I know :) ) .

So it hard to say whether those markets are any frothier than Selangor's is. But you're absolutely right about rental yields, though I believe that's true for all three markets.

Compare it against rents as Dean Baker did in order to predict the US bubble...

ReplyDeletehttp://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/reports/the-run-up-in-home-prices-is-it-real-or-is-it-another-bubble

There are ways of forecasting bubbles. But I think that you need to take a different tack than what you do above. Emulate those who succeeded in the past. It's a good policy.

Philip,

DeleteWish I could, but there is no publicly available time series on house rental rates in Malaysia. I've thought about using the rental series used to tabulate the CPI, but this data is mixed up with utilities prices (sub-index numbers are not published), and is not available as a time series either (only single index numbers are published).

A household income comparison would also be possible, but Malaysian household income surveys are only conducted once every two-three years and only summary data is published, which makes such comparisons pretty useless since house price increases have been concentrated geographically.

Under these constraints, what I've shown above is pretty much all we have for Malaysia.

TLDR

ReplyDelete