The last few months I’ve been forced into reading a lot of analyst reports. While for the most part it’s been worthwhile in terms of gauging what other people are thinking, there’s something about these reports that just bugs the hell out of me.

And that is the use – or rather, misuse – of the word “print”.

This isn’t even a problem just with our local guys either, I see the word often used by foreign bank and broker analysts as well. As in, “the latest GDP print” or “compared to the 4Q2013 BOP print”.

From the context, these guys are using the word “print” as synonymous with “record” or “report”. But in English, “print” doesn’t carry the same meaning, connotation or usage as the latter two words. To me, a “print” is a reproduction of something, not the thing itself.

So when people refer to a report as a “print”, I have visions of them queuing up to get reports as they’re published, and fastidiously making reference to their own individual copies while writing out their commentaries. Since this isn’t what anybody actually does, referring to economic data as coming from a “print” makes me cringe. It’s as if the form of a report (a publication) is more important than the data it conveys (the actual numbers).

Here’s the link to the Merriam-Webster definition, and here’s the link for the Oxford Dictionaries definition.

Nowhere in those definitions is “print” used in a way that could denote a report or the content of a report – only the process by which it is made (verb) or the form it can take (noun). The image that I usually carry in my head, when using “print” as a noun, is the same definition used by New York’s Museum of Modern Art:

“A print is a work of art made up of ink on paper and existing in multiple examples. It is created not by drawing directly on paper , but through an indirect transfer process.”

The stuff I have hanging on my office wall are prints. The data and reports issued by national statistical authorities are NOT prints.

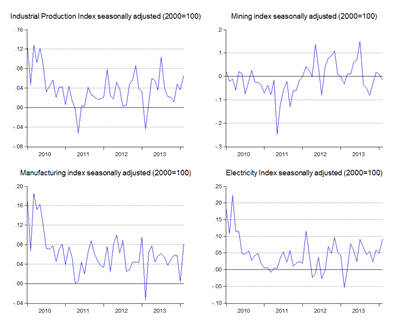

Unless you happen to think these are works of art.