If you remember my last post on monetary conditions in Malaysia, I was scratching my head over the apparent dichotomy between a whopping increase in the supply of securities into the capital and money markets, while prices defied gravity. Turns out I spoke too soon:

Yields on MGS rose across the board, but especially for 2-yr to 3-yr maturities (which was where the bulk of the issuance in November occurred). And of course, January we've seen the KLCI falling back along with markets across most of the region. I'll call that little mystery now over.

Other interest rates however have been moving the other way - yields on BNM bills and T-bills have dropped slightly, and the average lending rate has fallen to just above 4.8% (an all time low, AFAIK). All of this of course came before the latest Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting this week, which had language indicating that BNM might raise the OPR faster than the markets expect. Stay tuned for more on this subject.

There was little of note in terms of changes in the money supply situation, but there were some interesting things going on with BNM's balance sheet. There has been an injection of liquidity into the system the last couple months, though not anywhere near the scale of intervention in 2008:

This may just be a "normal" liquidity injection, as demand for cash rises at the year-end (people getting bonuses and what-not), as 2007-2008 was an aberration in terms of money demand. One last item:

BNM functions as the government's "banker", hence tracking government deposits with BNM is a useful barometer of actual government spending. With just RM0.5b in MGS redemptions in December, looks like a full RM6b was drawn down from the government's account. Note that there has been a tendency for government deposits to fall in the last couple of months of the year (seasonally adjusted, the level is actually higher than normal), but these aren't normal times. With no annual bonuses for the civil service declared, there isn't the typical one-time drain on financial resources, so I'm inclined to take this as proof of actual government consumption/investment - your tax dollars at work, stimulating the economy.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Dec 2009 Consumer Prices

Inflation has remained benign over the past year. DOS reports that consumer prices only rose 0.6% for the whole of 2009, but that mild figure hides a lot of movement underneath. For instance, the food and non-alcoholic beverages index rose 4.1%, but transport costs dropped 9.4%. And of course, 2008's inflation rate of 5.3% was the highest since the CPI rose 5.5% in 1982, so there's a base effect from the wild ride in fuel prices in 2008.

Minus that aberration, the CPI has been on a fairly steady and consistent uptrend (with little change in slope) since 2003 (index levels, 2000=100):

You can see this pattern in the growth (i.e. CPI inflation) figures as well:

Note that month-on-month growth is rarely above 0.3%, and only twice above 1% in the last ten years. The core inflation story is even steadier - at least using my pseudo-core measure (dropping food and trasnport indexes):

Core monthly inflation averages out at about 0.1%, so most of the upward pressure on inflation is coming from food and transport costs. Even then there are some counterbalances, such as clothing and communication prices, which have consistently been going down over at least the last five years:

So this coming year, sans another zoom up in oil prices, inflation is probably going to stay quiet, even with the new petrol subsidy scheme coming into effect in the middle of the year and even as BNM keeps interest rates low.

The proximate problem that BNM has to deal with vis-a-vis inflation is really structural. Consider the continuous drop in clothing prices, which is primarily a result of the shift of textile manufacturers to low-cost production bases in places like Indonesia and Vietnam (and yes, China). Part of the problem facing many monetary authorities this decade is that with the almost sudden emergence of these low-cost exporting economies in the late 1990s, global goods prices have held steady or dropped which obviously colours consumer decisions on spending. Yet the increase in consumption did not result in inflationary pressures (at least until 2007-2008), or upward pressure on wages or interest rates. Hence central banks stood by, despite a consumption boom and bubbles in many asset markets.

How we deal with this issue in the future is still being debated, though I suspect that eventually the problem will solve itself over the next decade as labour costs continue to rise in the exporting economies.

Technical Notes:

1. Consumer Price Index report from DOS.

2. Want to know how to get quarterly or annual index numbers from the monthly numbers? Simple...just average out the monthly indexes for the period in question. For instance, the Q1 2009 CPI number is just the average of January-March 2009 monthly index readings. The 2009 CPI is gotten by averaging the monthly index numbers from January to December 2009.

Minus that aberration, the CPI has been on a fairly steady and consistent uptrend (with little change in slope) since 2003 (index levels, 2000=100):

You can see this pattern in the growth (i.e. CPI inflation) figures as well:

Core monthly inflation averages out at about 0.1%, so most of the upward pressure on inflation is coming from food and transport costs. Even then there are some counterbalances, such as clothing and communication prices, which have consistently been going down over at least the last five years:

So this coming year, sans another zoom up in oil prices, inflation is probably going to stay quiet, even with the new petrol subsidy scheme coming into effect in the middle of the year and even as BNM keeps interest rates low.

The proximate problem that BNM has to deal with vis-a-vis inflation is really structural. Consider the continuous drop in clothing prices, which is primarily a result of the shift of textile manufacturers to low-cost production bases in places like Indonesia and Vietnam (and yes, China). Part of the problem facing many monetary authorities this decade is that with the almost sudden emergence of these low-cost exporting economies in the late 1990s, global goods prices have held steady or dropped which obviously colours consumer decisions on spending. Yet the increase in consumption did not result in inflationary pressures (at least until 2007-2008), or upward pressure on wages or interest rates. Hence central banks stood by, despite a consumption boom and bubbles in many asset markets.

How we deal with this issue in the future is still being debated, though I suspect that eventually the problem will solve itself over the next decade as labour costs continue to rise in the exporting economies.

Technical Notes:

1. Consumer Price Index report from DOS.

2. Want to know how to get quarterly or annual index numbers from the monthly numbers? Simple...just average out the monthly indexes for the period in question. For instance, the Q1 2009 CPI number is just the average of January-March 2009 monthly index readings. The 2009 CPI is gotten by averaging the monthly index numbers from January to December 2009.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Somebody Making Sense - For Once

Caught this yesterday:

"Amendments to the Employment Act 1955 and the increase in the number of childcare centres run by the private sector are expected to encourage locals to take up employment in certain sectors and minimise the country’s dependence on foreign workers...Deputy Human Resources Minister Datuk Maznah Mazlan said the amendments, among others, would allow workers to work on shift or on a part-time basis, apart from enjoying protection in terms of wages, welfare and annual leave, she said."

This is very, very important...much more so than implementing a minimum wage. The key stat mentioned in the article is 6.5 million people in the working age brackets (15-64) that are not in the work force.

Want a high income economy? Get everyone involved - at the moment, the income of some 11 million workers is spread over 26 million citizens. If you get even half of the missing to enter the workforce, we're talking about a 25% boost to labour supply as well as an unquantified boost to consumption demand.

I'm not blind to the potential difficulties here - some of those not officially in the workforce are actually working in the "black" economy; some (many actually, a full 2.5 million of the population are between ages 15-19) are still in the education system. But there's no doubt that many women have opted out of formal employment due to childcare concerns. Addressing their concerns will go a long way, as will bolstering the legal and regulatory protections extended to part-time and self employed workers (I talked about this in passing here).

I'm doing some research into demographics right now (just downloaded the data yesterday), so stay tuned for more on this issue.

Update:

Just to underscore the point I'm making, a chart from the DOS Q3 2009 Labour Force Survey:

"Amendments to the Employment Act 1955 and the increase in the number of childcare centres run by the private sector are expected to encourage locals to take up employment in certain sectors and minimise the country’s dependence on foreign workers...Deputy Human Resources Minister Datuk Maznah Mazlan said the amendments, among others, would allow workers to work on shift or on a part-time basis, apart from enjoying protection in terms of wages, welfare and annual leave, she said."

This is very, very important...much more so than implementing a minimum wage. The key stat mentioned in the article is 6.5 million people in the working age brackets (15-64) that are not in the work force.

Want a high income economy? Get everyone involved - at the moment, the income of some 11 million workers is spread over 26 million citizens. If you get even half of the missing to enter the workforce, we're talking about a 25% boost to labour supply as well as an unquantified boost to consumption demand.

I'm not blind to the potential difficulties here - some of those not officially in the workforce are actually working in the "black" economy; some (many actually, a full 2.5 million of the population are between ages 15-19) are still in the education system. But there's no doubt that many women have opted out of formal employment due to childcare concerns. Addressing their concerns will go a long way, as will bolstering the legal and regulatory protections extended to part-time and self employed workers (I talked about this in passing here).

I'm doing some research into demographics right now (just downloaded the data yesterday), so stay tuned for more on this issue.

Update:

Just to underscore the point I'm making, a chart from the DOS Q3 2009 Labour Force Survey:

Sunday, January 17, 2010

Ruminations On The Minimum Wage

And so it begins. From The Star:

"The Government wants to study the minimum wage mechanism so that workers are better paid in line with efforts to transit to a high-income economy...Human Resources Minister Datuk Dr S. Subramaniam said his ministry was looking at various ways practised worldwide to determine one that suits the country best...This is also aimed at reducing the dependence on foreign workers as attractive wages will lure locals to take up jobs they previously shy away from."

...and a sensible rebuttal:

"A minimum wage will not contribute to the development of a high-income economy, says an academic from the National University of Singapore...'Instead, a high-income economy is driven by technology and key competitive industries, and maintained through a stable human capital,' said Assoc Prof Shandre M. Thangavelu, who is with the university’s Economics Department...'The more developed human capital is, the higher wages can go, in line with increased productivity,' he added."

There is an extensive literature on the impact of a minimum wage, but the aggregate impact is in theory is pretty unambiguous. Since a minimum wage effectively puts a floor on wages above the market clearing wage, then assuming "normal" demand and supply curves for labour, labour demand should fall while labour supply should increase - in short, unemployment. A more nuanced view is that since a minimum wage is effectively only operative in the low-cost labour market, then unemployment should only rise in the low-wage labour sector, as this paper finds for the US and France (abstract):

"We use longitudinal individual wage and employment data for young people in France and the United States to investigate the effect of intertemporal changes in an individual's status vis-...-vis [sic] the real minimum wage on employment transition rates. We find that movements in both French and American real minimum wages are associated with relatively important employment effects in general, and very strong effects on workers employed at the minimum wage. In the French case, albeit imprecisely estimated, a 1% increase in the real minimum wage decreases the employment probability of a young man currently employed at the minimum wage by 2.5%. In the United States, a decrease in the real minimum of 1% increases the probability that a young man employed at the minimum wage came from nonemployment by 2.2%. These effects get worse with age in the United States, and are mitigated by eligibility for special employment promotion contracts in France."

Malaysia is an interesting case, as the low wage sector is dominated by foreign nationals. Implementing a minimum wage should indeed lower demand for foreign labour, but it doesn't follow that these jobs would then go to locals. Some portion of these jobs will just disappear, from businesses already on the margin. Nor will it necessarily improve the situation with respect to illegals, as the higher wage floor means Malaysia becomes even more attractive as an employer. Taken together, the impact on average incomes is therefore a balance between the increase in incomes against the loss of employment, and are likely to cancel each other out. That means a minimum wage should not be used as part of a Malaysian strategy to become a high-income country.

A further effect is that a minimum wage is also effectively a tax on businesses, as this paper shows (abstract):

"Although there is a large literature on the economic effects of minimum wages on labour market outcomes (especially employment), there is much less evidence on their impact on firm performance. In this paper we consider a very under-studied area - the impact of minimum wages on firm profitability. The analysis exploits the changes induced by the introduction of a national minimum wage to the UK labour market in 1999, using pre-policy information on the distribution of wages to construct treatment and comparison groups and implement a difference in differences approach. We report evidence showing that firm profitability was significantly reduced (and wages significantly raised) by the minimum wage introduction. This emerges from separate analyses of two distinct types of firm level panel data (one on firms in a very low wage sector, UK residential care homes, and a second on firms across all sectors). We find that net entry rates have fallen, but that the changes in exit and entry rates are statistically insignificant."

I'll go one further - a minimum wage is also effectively a tax on the higher income brackets. As a minimum wage is a rise in input costs, there's an incentive for businesses to pass on these costs to consumers. Insofar as we're talking about low-wage export industries, that's not necessarily a problem for consumers although there would be a negative effect on Malaysia's export competitiveness. However, this will also have an effect on local businesses - the price you pay for teh tarik is going to go up as well.

One of the characteristics of high-income economies is also their high-cost structure (I've covered this before in a few posts, this one for instance). So implementing a minimum wage is like creating a high income economy - but without the high income. The only substantive argument in favour of a minimum wage is for income redistribution, as this paper suggests (abstract):

"This paper provides a theoretical analysis of optimal minimum wage policy in a perfectly competitive labor market. We show that a binding minimum wage -- while leading to unemployment -- is nevertheless desirable if the government values redistribution toward low wage workers and if unemployment induced by the minimum wage hits the lowest surplus workers first. This result remains true in the presence of optimal nonlinear taxes and transfers. In that context, a minimum wage effectively rations the low skilled labor that is subsidized by the optimal tax/transfer system, and improves upon the second-best tax/transfer optimum. When labor supply responses are along the extensive margin, a minimum wage and low skill work subsidies are complementary policies; therefore, the co-existence of a minimum wage with a positive tax rate for low skill work is always (second-best) Pareto inefficient. We derive formulas for the optimal minimum wage (with and without optimal taxes) as a function of labor supply and demand elasticities and the redistributive tastes of the government. We also present some illustrative numerical simulations."

On that basis a minimum wage, especially one high enough over the market-clearing level to actually have an effective impact on real low wage incomes, is one way to mitigate the effects of a high cost structure on the lower income group in a high-income economy. A minimum wage should be used as an adjunct to a high income strategy, not as an enabling mechanism.

It's not necessarily a bad idea, but let's call it as it is. Like the talk about appreciating the Ringgit to raise domestic income levels, we might be putting the cart before the horse again.

"The Government wants to study the minimum wage mechanism so that workers are better paid in line with efforts to transit to a high-income economy...Human Resources Minister Datuk Dr S. Subramaniam said his ministry was looking at various ways practised worldwide to determine one that suits the country best...This is also aimed at reducing the dependence on foreign workers as attractive wages will lure locals to take up jobs they previously shy away from."

...and a sensible rebuttal:

"A minimum wage will not contribute to the development of a high-income economy, says an academic from the National University of Singapore...'Instead, a high-income economy is driven by technology and key competitive industries, and maintained through a stable human capital,' said Assoc Prof Shandre M. Thangavelu, who is with the university’s Economics Department...'The more developed human capital is, the higher wages can go, in line with increased productivity,' he added."

There is an extensive literature on the impact of a minimum wage, but the aggregate impact is in theory is pretty unambiguous. Since a minimum wage effectively puts a floor on wages above the market clearing wage, then assuming "normal" demand and supply curves for labour, labour demand should fall while labour supply should increase - in short, unemployment. A more nuanced view is that since a minimum wage is effectively only operative in the low-cost labour market, then unemployment should only rise in the low-wage labour sector, as this paper finds for the US and France (abstract):

"We use longitudinal individual wage and employment data for young people in France and the United States to investigate the effect of intertemporal changes in an individual's status vis-...-vis [sic] the real minimum wage on employment transition rates. We find that movements in both French and American real minimum wages are associated with relatively important employment effects in general, and very strong effects on workers employed at the minimum wage. In the French case, albeit imprecisely estimated, a 1% increase in the real minimum wage decreases the employment probability of a young man currently employed at the minimum wage by 2.5%. In the United States, a decrease in the real minimum of 1% increases the probability that a young man employed at the minimum wage came from nonemployment by 2.2%. These effects get worse with age in the United States, and are mitigated by eligibility for special employment promotion contracts in France."

Malaysia is an interesting case, as the low wage sector is dominated by foreign nationals. Implementing a minimum wage should indeed lower demand for foreign labour, but it doesn't follow that these jobs would then go to locals. Some portion of these jobs will just disappear, from businesses already on the margin. Nor will it necessarily improve the situation with respect to illegals, as the higher wage floor means Malaysia becomes even more attractive as an employer. Taken together, the impact on average incomes is therefore a balance between the increase in incomes against the loss of employment, and are likely to cancel each other out. That means a minimum wage should not be used as part of a Malaysian strategy to become a high-income country.

A further effect is that a minimum wage is also effectively a tax on businesses, as this paper shows (abstract):

"Although there is a large literature on the economic effects of minimum wages on labour market outcomes (especially employment), there is much less evidence on their impact on firm performance. In this paper we consider a very under-studied area - the impact of minimum wages on firm profitability. The analysis exploits the changes induced by the introduction of a national minimum wage to the UK labour market in 1999, using pre-policy information on the distribution of wages to construct treatment and comparison groups and implement a difference in differences approach. We report evidence showing that firm profitability was significantly reduced (and wages significantly raised) by the minimum wage introduction. This emerges from separate analyses of two distinct types of firm level panel data (one on firms in a very low wage sector, UK residential care homes, and a second on firms across all sectors). We find that net entry rates have fallen, but that the changes in exit and entry rates are statistically insignificant."

I'll go one further - a minimum wage is also effectively a tax on the higher income brackets. As a minimum wage is a rise in input costs, there's an incentive for businesses to pass on these costs to consumers. Insofar as we're talking about low-wage export industries, that's not necessarily a problem for consumers although there would be a negative effect on Malaysia's export competitiveness. However, this will also have an effect on local businesses - the price you pay for teh tarik is going to go up as well.

One of the characteristics of high-income economies is also their high-cost structure (I've covered this before in a few posts, this one for instance). So implementing a minimum wage is like creating a high income economy - but without the high income. The only substantive argument in favour of a minimum wage is for income redistribution, as this paper suggests (abstract):

"This paper provides a theoretical analysis of optimal minimum wage policy in a perfectly competitive labor market. We show that a binding minimum wage -- while leading to unemployment -- is nevertheless desirable if the government values redistribution toward low wage workers and if unemployment induced by the minimum wage hits the lowest surplus workers first. This result remains true in the presence of optimal nonlinear taxes and transfers. In that context, a minimum wage effectively rations the low skilled labor that is subsidized by the optimal tax/transfer system, and improves upon the second-best tax/transfer optimum. When labor supply responses are along the extensive margin, a minimum wage and low skill work subsidies are complementary policies; therefore, the co-existence of a minimum wage with a positive tax rate for low skill work is always (second-best) Pareto inefficient. We derive formulas for the optimal minimum wage (with and without optimal taxes) as a function of labor supply and demand elasticities and the redistributive tastes of the government. We also present some illustrative numerical simulations."

On that basis a minimum wage, especially one high enough over the market-clearing level to actually have an effective impact on real low wage incomes, is one way to mitigate the effects of a high cost structure on the lower income group in a high-income economy. A minimum wage should be used as an adjunct to a high income strategy, not as an enabling mechanism.

It's not necessarily a bad idea, but let's call it as it is. Like the talk about appreciating the Ringgit to raise domestic income levels, we might be putting the cart before the horse again.

Friday, January 15, 2010

Lies, Damn Lies Part II

I thought I might take a little time to clarify a few things from my previous post.

First, why does the exchange rate regime matter in terms of movements in reserves? In theory, a fixed exchange rate regime requires that a central bank buys and sells foreign currency to maintain the exchange rate parity between the domestic currency and the target currency, which is typically either the USD (a'la Bretton Woods arrangements from 1944-1972) or a "basket" of currencies. Both China (implict) and Hong Kong (very explicit) use fixed rate regimes. Singapore is slightly different - MAS uses an exchange rate target to manage domestic monetary conditions, although the mechanism is similar.

With a fixed rate target, reserves will accumulate or be lost with changes in trade and capital flows - if there is an excess of inflows (trade surplus, or portfolio inflows), then demand for local currency exceeds foreign currency and the exchange rate should appreciate.

To maintain parity, the central bank creates domestic money (yes, out of thin air - it's only an accounting entry), and uses this to buy foreign currency. This has the effect of meeting the increased demand for local currency, as well as simultaneously creating greater demand for foreign currency, and hopefully balancing out the market exchange rate. In this scenario, the foreign currency bought by the central bank goes into its foreign exchange reserves account (on the asset side of the central bank's balance sheet), while liabilities (domestic cash) increases by the same portion.

A secondary effect of these transactions is thus a de facto increase in the domestic money supply and downward pressure on interest rates, since money was created to buy the foreign currency. If this is a concern to the central bank, then it "sterilises" the intervention by draining liquidity from the money market through the issue of securities. The total net effect of a full intervention and sterilisation exercise is thus an increase in reserves (assets) and an increase in issued securities (on the liabilities side), with the money supply staying pat.

The reverse happens when there is an outflow and full intervention - reduction in reserves (asset side) and a reduction in money supply (liabilities) in the case of non-sterilisation, or reduction in securities (liabilities) in the case of sterilisation.

There's actually only one effective difference between money and securities - they're both liabilities of the central bank, but from the banking system's perspective only money can be used to further credit (i.e. loans to you and me). Hence, in a fixed rate regime, domestic monetary policy operations are far more complicated.

Under a free float regime, of course, there's no apparent necessity for intervention at all and thus no incentive to accumulate reserves, except for one big reason I'll cover later.

So given the narrative above, here's what happened in Malaysia in 2008:

1. Big changes in inflows and outflows

First the run-up in commodity prices increased Malaysia's exports earnings beyond the average, up to about the middle of 2008 (trade balance, balance of payments basis, RM millions):

Then, as the financial crisis took hold in the latter half of 2008, there was a huge flight to safety by foreign investors:

2. And here's what the commodity and financial markets were doing:

Notice the symmetry between all the markets. Also note that investors (the smart money) had already begun to pull out before the markets peaked.

3. The impact on financial institutions:

Here's one good reason why a central bank would accumulate reserves even under a floating regime - if foreign liabilities exceeds assets, then there is the potential for an external default in either the private sector or within the banking system itself - not from insolvency, but through lack of liquidity. You have the money, but not the right kind of money. To avoid that, you save up on the right kinds of external money to make sure you can meet all your external obligations i.e. accumulate reserves.

Another way of having this insurance is by doing swap agreements with other central banks, thus creating a collective pool of external reserves i.e. what we're doing now under the Chiang Mai Initiative. This reduces the cost of hoarding on your own.

4. And this what BNM did to manage the whole shebang (all items from BNM's balance sheet, RM millions):

Note how this fits into the narrative above. With upward pressure on the Ringgit in 2007-2008, BNM intervened by supplying Ringgit to the market in exchange for foreign currency, while simultaneously issuing BNM bills to limit growth in the domestic money supply. After commodity prices started dropping, and portfolio investors started pulling out, the opposite happened - intervention to support the Ringgit, and buying and cancelling of bills to ensure the domestic money market remain liquid.

While BNM does not have an exchange rate target (at least I don't think they do), from comments by the Governor they have made a commitment to reduce volatility - in other words, they won't stop a depreciation or appreciation but they will limit excessive movements.

Since the inflow of trade receipts in 2007 and early 2008 weren't viewed as sustainable, they obviously felt that upward pressure on the Ringgit had to be capped to avoid a sharp depreciation afterward. And when inflows did turn into outflows, BNM also acted to limit the downward movement. These operations are consistent with a managed float regime, where volatility reduction is a goal.

Hence the sharp changes in reserves, as well as the changes in BNM bills left outstanding in the market - intervention was also sterilised to maintain BNM's real target, which is the short-term domestic interest rate:

5. One last point on the statutory reserve requirement:

The money multiplier (see this post on what this means) based on banks' reserve deposit assets:

...and reserve deposits as a percentage of loans:

As I said in the last post, banks aren't basing credit expansion on the reserve ratio, but rather on the capital ratio:

A statutory reserve requirement of 1% implies a potential money multiplier of 100x, while 0.5% implies 200x. The actual average is actually only around 4x, in contrast to the leverage ratio which was almost right to the limit of what's allowable.

First, why does the exchange rate regime matter in terms of movements in reserves? In theory, a fixed exchange rate regime requires that a central bank buys and sells foreign currency to maintain the exchange rate parity between the domestic currency and the target currency, which is typically either the USD (a'la Bretton Woods arrangements from 1944-1972) or a "basket" of currencies. Both China (implict) and Hong Kong (very explicit) use fixed rate regimes. Singapore is slightly different - MAS uses an exchange rate target to manage domestic monetary conditions, although the mechanism is similar.

With a fixed rate target, reserves will accumulate or be lost with changes in trade and capital flows - if there is an excess of inflows (trade surplus, or portfolio inflows), then demand for local currency exceeds foreign currency and the exchange rate should appreciate.

To maintain parity, the central bank creates domestic money (yes, out of thin air - it's only an accounting entry), and uses this to buy foreign currency. This has the effect of meeting the increased demand for local currency, as well as simultaneously creating greater demand for foreign currency, and hopefully balancing out the market exchange rate. In this scenario, the foreign currency bought by the central bank goes into its foreign exchange reserves account (on the asset side of the central bank's balance sheet), while liabilities (domestic cash) increases by the same portion.

A secondary effect of these transactions is thus a de facto increase in the domestic money supply and downward pressure on interest rates, since money was created to buy the foreign currency. If this is a concern to the central bank, then it "sterilises" the intervention by draining liquidity from the money market through the issue of securities. The total net effect of a full intervention and sterilisation exercise is thus an increase in reserves (assets) and an increase in issued securities (on the liabilities side), with the money supply staying pat.

The reverse happens when there is an outflow and full intervention - reduction in reserves (asset side) and a reduction in money supply (liabilities) in the case of non-sterilisation, or reduction in securities (liabilities) in the case of sterilisation.

There's actually only one effective difference between money and securities - they're both liabilities of the central bank, but from the banking system's perspective only money can be used to further credit (i.e. loans to you and me). Hence, in a fixed rate regime, domestic monetary policy operations are far more complicated.

Under a free float regime, of course, there's no apparent necessity for intervention at all and thus no incentive to accumulate reserves, except for one big reason I'll cover later.

So given the narrative above, here's what happened in Malaysia in 2008:

1. Big changes in inflows and outflows

First the run-up in commodity prices increased Malaysia's exports earnings beyond the average, up to about the middle of 2008 (trade balance, balance of payments basis, RM millions):

Then, as the financial crisis took hold in the latter half of 2008, there was a huge flight to safety by foreign investors:

2. And here's what the commodity and financial markets were doing:

Notice the symmetry between all the markets. Also note that investors (the smart money) had already begun to pull out before the markets peaked.

3. The impact on financial institutions:

Here's one good reason why a central bank would accumulate reserves even under a floating regime - if foreign liabilities exceeds assets, then there is the potential for an external default in either the private sector or within the banking system itself - not from insolvency, but through lack of liquidity. You have the money, but not the right kind of money. To avoid that, you save up on the right kinds of external money to make sure you can meet all your external obligations i.e. accumulate reserves.

Another way of having this insurance is by doing swap agreements with other central banks, thus creating a collective pool of external reserves i.e. what we're doing now under the Chiang Mai Initiative. This reduces the cost of hoarding on your own.

4. And this what BNM did to manage the whole shebang (all items from BNM's balance sheet, RM millions):

Note how this fits into the narrative above. With upward pressure on the Ringgit in 2007-2008, BNM intervened by supplying Ringgit to the market in exchange for foreign currency, while simultaneously issuing BNM bills to limit growth in the domestic money supply. After commodity prices started dropping, and portfolio investors started pulling out, the opposite happened - intervention to support the Ringgit, and buying and cancelling of bills to ensure the domestic money market remain liquid.

While BNM does not have an exchange rate target (at least I don't think they do), from comments by the Governor they have made a commitment to reduce volatility - in other words, they won't stop a depreciation or appreciation but they will limit excessive movements.

Since the inflow of trade receipts in 2007 and early 2008 weren't viewed as sustainable, they obviously felt that upward pressure on the Ringgit had to be capped to avoid a sharp depreciation afterward. And when inflows did turn into outflows, BNM also acted to limit the downward movement. These operations are consistent with a managed float regime, where volatility reduction is a goal.

Hence the sharp changes in reserves, as well as the changes in BNM bills left outstanding in the market - intervention was also sterilised to maintain BNM's real target, which is the short-term domestic interest rate:

5. One last point on the statutory reserve requirement:

The money multiplier (see this post on what this means) based on banks' reserve deposit assets:

...and reserve deposits as a percentage of loans:

As I said in the last post, banks aren't basing credit expansion on the reserve ratio, but rather on the capital ratio:

A statutory reserve requirement of 1% implies a potential money multiplier of 100x, while 0.5% implies 200x. The actual average is actually only around 4x, in contrast to the leverage ratio which was almost right to the limit of what's allowable.

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Lies, Damn Lies, and Then There Are Statistics

UBS Securities Asia Ltd has issued a report that has generated a bit of a buzz in the online media titled "Malaysia - Another Bizarre Story" (try here, alternate here). The headlines in the online media however are less timid:

Ye Gods.

I’ve covered the issue of capital flight before in this post (read the comments for an interesting discussion). There’s no doubt that capital has been leaving the country in the aftermath of 1997-98, which in my opinion and from anecdotal evidence is largely due to domestic investment abroad. However, this UBS report is highly misleading as it purports to show that large amounts of capital left the country in 2009, which isn’t the case at all - at least, not any worse than it usually has.

Here’s my view (point by point, in blue) of where this report went wrong.

“Question: which Asian country had the biggest FX reserve losses in 2009? The answer is Malaysia, and by a very wide margin; we estimate that official reserves fell by well more than one-quarter on a valuation-adjusted basis.”

This is the main evidence that the report uses to justify its conclusion. But note that the basis of this estimate is from peak 2008 levels against current levels, which is more than a little disingenuous (look at notes for the first chart in the report). The assessment of “more than a quarter” loss suffers from what’s called the “base” effect – if you use a period with a high denominator, you can get negative growth even if the actual levels are increasing (international reserves, RM millions):

I put in a longer sample period so it’s easier to see what’s going on. Using a more conventional year on year calculation, this is what you get (log annual changes):

See what I mean? For most of 2009 growth in reserves was negative, despite the fact that the actual level of reserves was largely flat to increasing. Malaysia suffered technical deflation for much of 2009 for much the same reason, but I don’t hear anyone crowing over consumer prices falling.

Here's what monthly growth looked like (log monthly changes):

Here's what monthly growth looked like (log monthly changes):

Through the whole of 2009, we've had exactly three months where reserve growth was negative, while the rest of the year saw reserves rising. This type of problem is the reason why I've consistently advocated looking at levels rather than growth metrics during times of violent change. You simply miss a lot of what's going on by using a period-to-period percentage change approach.

I’m also a little suspicious of the claim that the estimates were valuation adjusted – BNM already books revaluation losses and gains every quarter. If you revalue again based on published statistics, that would constitute double counting and would exacerbate movements in reserves.

I’m also a little suspicious of the claim that the estimates were valuation adjusted – BNM already books revaluation losses and gains every quarter. If you revalue again based on published statistics, that would constitute double counting and would exacerbate movements in reserves.

“Other structural surplus neighbors like China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand have all seen sizeable increases in FX reserves over the past 12 months … and yet Malaysian reserves nearly collapsed.”

Sloppy analysis – reserves at end 2008 stood at RM317.5 billion, versus RM331.3 billion at end 2009, including a revaluation loss of over RM10 billion for 2009 as a whole. That means a net increase of RM13.8 billion over a 12 month period – sure doesn’t look like a collapse to me.

More important, the first three countries listed all have an explicit exchange rate target. China has effectively halted Yuan appreciation against the USD in the last year and a half, Hong Kong has a currency board arrangement with the USD which effectively means forex reserves back the money supply, and Singapore explicitly uses the exchange rate as the instrument for implementing monetary policy unlike the more conventional interest rate target as used in Malaysia. I don’t know off-hand how Taiwan manages monetary policy (Taiwan is not an IMF member, and aren’t categorized within the IMF’s exchange regime framework), but Thailand uses a managed float with an inflation target, also implying intervention in foreign exchange markets.

Why this is important is that the countries listed all accumulate or lose reserves due to implicit or explicit exchange rate targets. Malaysia does not fall under that category under either a de facto or de jure basis, and I’ve gone on record to state that I don’t think BNM has an exchange rate target for the Ringgit at all. Hence, if there is no intervention, there should be effectively little to no change in reserves – which is what happened in 2009.

So what’s the story for 2008, because there was a massive loss in reserves back then? Looking at the reserve levels, you see a mild run-up from 2005 to 2006, and then acceleration from end-2006 to about mid-2008. Not coincidentally, reserve accumulation happened simultaneously with the commodity bubble of those years:

That's the main difference between Malaysia and the other countries we were compared to in the report - we are a commodity exporting country, none of the others are. Given that exports of commodities didn’t change much in volume but export receipts did, we had an abnormal influx of income that was more nominal than real. In the aftermath of the collapse in prices post July 2008, we had a drop in income that was also more nominal than real. Hence, from BNM’s perspective, the appreciation of the exchange rate (as well as the money supply impact of the inflow of trade receipts) warranted intervention to mitigate the Ringgit’s (and the money supply's) rise during the boom, and limit the Ringgit’s (sharp) fall (and the potential contraction in the money supply) in its aftermath. In addition, BNM had to meet the sudden demand for USD from the banking system as depositors and investors pulled out:

If you look at newspaper reports at the time (4Q 2008), BNM as good as admitted buying MYR against USD to support the currency:

Now if these factors are taken away – receipts from a commodity bubble boosting forex supply within the banking system and forcing an overshooting appreciation of the exchange rate, we would not have had reserve accumulation in 2007-2008 in the first place, and reserve accumulation would simply be on the same trend as it was from 2005-2006. And we wouldn't be arguing about a loss of reserves we probably shouldn't have had in the first place.

3. “And this despite a massive, unprecedented decline in high-powered “base” money, as shown in Chart 4. Indeed, over the past 12 months Malaysia recorded one of the biggest base money contractions in the entire EM world, matched only by the Baltic states (Chart 5). This is in part because the Malaysian central bank responded with a sharp drop in reserve requirements to keep banks liquid … but still, we can’t help but note that the domestic financial system seems uniquely unaffected by apparent capital outflows.”

This one’s a bit funny – the writer was obviously not referring to M1 (currency + demand deposits) (RM millions; and log annual changes):

He’s referring to base money which is a bit different – currency + bank reserve deposits. This is a rather funny metric to use, because under a modern regulatory system, bank reserve deposits are barely relevant. As long as the statutory reserve ratio is below the risk-weighted capital ratio (8% under the original Basle requirements, somewhat more nebulous under Basle II), then the money multiplier is effectively limited by the capital ratio and not the reserve ratio.

Hence BNM’s cut in the reserve ratio was a token and not an effective policy change, unlike the situation in China for instance where the reserve ratio is one of the primary instruments for managing the supply of credit (because it's double the capital ratio). BNM hasn’t seriously used the reserve ratio as a policy instrument since before the 1997 crisis.

Hence BNM’s cut in the reserve ratio was a token and not an effective policy change, unlike the situation in China for instance where the reserve ratio is one of the primary instruments for managing the supply of credit (because it's double the capital ratio). BNM hasn’t seriously used the reserve ratio as a policy instrument since before the 1997 crisis.

What’s even funnier is the description of the cut as “sharp” – it was a 50% cut, which sounds big until you realize that it was from 1% to 0.5%. And the banks have more or less ignored the reserve requirement anyway – the banking system has been flush with cash for years, and they haven’t bothered to lend out the excess (banking system deposits with BNM in RM millions; loan-deposit ratio):

Hence there should be no surprise that interest rates have trended lower in 2009 – there hasn’t actually been a large outflow of capital (and hence a contraction in the money supply), there hasn’t been a massive loss of reserves, and...there isn’t really a story here except maybe UBS wanting to sell something.

(H/T Hafiz Noor Shams - free plug for you, mate!)

(H/T Hafiz Noor Shams - free plug for you, mate!)

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Nov 2009 Industrial Production: It Sucked

It's hard to take any positives from November's numbers - it's been a weird month. Today's IPI report is just par for the course:

It's not exactly the falling off the cliff feeling from last year, but the numbers are disappointing after October's (log monthly changes):

On the other hand, apart from mining output (what's up with that? a reaction to the runup in oil prices?), looking at the index numbers it looks like the same story as what happened with trade - a return to the recovery trend rather than the beginning of a new downturn. Again, we're looking at the delayed effect of Hari Raya blues. If that's true than December should see much better numbers, as it normally does, with at least some growth evident.

It's not exactly the falling off the cliff feeling from last year, but the numbers are disappointing after October's (log monthly changes):

On the other hand, apart from mining output (what's up with that? a reaction to the runup in oil prices?), looking at the index numbers it looks like the same story as what happened with trade - a return to the recovery trend rather than the beginning of a new downturn. Again, we're looking at the delayed effect of Hari Raya blues. If that's true than December should see much better numbers, as it normally does, with at least some growth evident.

Friday, January 8, 2010

November 2009 Trade: Back To Normal

Yesterday's trade report from Matrade disappointed on nearly all counts, with growth turning negative for exports and slowing for imports (log annual and monthly changes, seasonally adjusted):

Again, the consensus estimate got blown out of the water, but this time in the opposite direction - +2.5% export growth versus actual realization of -3.4%.

In my last post, I thought exports would hit the top end of the forecast range - I got it wrong too. Instead exports came back to the middle of the range (and very closely, too), which means I probably should have more trust in my own models than in prognostication.

This also suggests that the first of my two hypotheses was probably more correct - October's outsize growth was caused more by a catching up of shipments after Hari Raya than a signal that we are entering a more sustainable recovery in export volumes.

On that score, December's trade numbers should show some improvement over November, but not too much:

Seasonally adjusted model

Point forecast:RM48,236m, Range forecast:RM54,231m-RM42,241

Seasonal difference model

Point forecast:RM51,242m, Range forecast:RM58,421m-RM44,064m

Technical Notes:

Trade data from MATRADE.

Again, the consensus estimate got blown out of the water, but this time in the opposite direction - +2.5% export growth versus actual realization of -3.4%.

In my last post, I thought exports would hit the top end of the forecast range - I got it wrong too. Instead exports came back to the middle of the range (and very closely, too), which means I probably should have more trust in my own models than in prognostication.

This also suggests that the first of my two hypotheses was probably more correct - October's outsize growth was caused more by a catching up of shipments after Hari Raya than a signal that we are entering a more sustainable recovery in export volumes.

On that score, December's trade numbers should show some improvement over November, but not too much:

Seasonally adjusted model

Point forecast:RM48,236m, Range forecast:RM54,231m-RM42,241

Seasonal difference model

Point forecast:RM51,242m, Range forecast:RM58,421m-RM44,064m

Technical Notes:

Trade data from MATRADE.

Labels:

exports,

external trade,

imports,

seasonal adjustment,

seasonal effects

Thursday, January 7, 2010

Perverse Incentives And The Sugar Subsidy

The Consumer Association of Penang is calling for a halt to the sugar subsidy:

"CAP president S.M. Mohamed Idris said sugar is 'nothing less than a toxic substance' and Malaysians are consuming an average of 26 teaspoons of sugar a day.

'The recent 20sen increase in each kilogram of sugar means the Government will still end up subsidising a sinful sum of RM1bil in 2010, based on a subsidy of 80sen per kilogram...The sweet indulgence has resulted in nearly 1.2 million Malaysians with diabetes and more than 98% of them are type 2 diabetes,' he said at the CAP office Wednesday.

Referring to diabetes as the 'mother of diseases,' he said it made no sense for the Government to provide the sugar subsidy."

Actually, why stop at sugar? And why stop at abolishing subsidies?

The type of perverse incentives resulting from below market-clearing price fixing that can create a social health problem (and thus increase health costs, which are also subsidised), is also present in other subsidised products. If that's the case, a duty on sugar makes more sense from a social welfare perspective - as does a tax on petrol, for much the same reasons.

"CAP president S.M. Mohamed Idris said sugar is 'nothing less than a toxic substance' and Malaysians are consuming an average of 26 teaspoons of sugar a day.

'The recent 20sen increase in each kilogram of sugar means the Government will still end up subsidising a sinful sum of RM1bil in 2010, based on a subsidy of 80sen per kilogram...The sweet indulgence has resulted in nearly 1.2 million Malaysians with diabetes and more than 98% of them are type 2 diabetes,' he said at the CAP office Wednesday.

Referring to diabetes as the 'mother of diseases,' he said it made no sense for the Government to provide the sugar subsidy."

Actually, why stop at sugar? And why stop at abolishing subsidies?

The type of perverse incentives resulting from below market-clearing price fixing that can create a social health problem (and thus increase health costs, which are also subsidised), is also present in other subsidised products. If that's the case, a duty on sugar makes more sense from a social welfare perspective - as does a tax on petrol, for much the same reasons.

Wednesday, January 6, 2010

The Mysterious Affair Of MGS Yields And The Maxis IPO

There was some weird happenings in November, which I'll get to in a bit. It'd makes for an interesting whodunit, if I could just get a good idea as to who the culprits are. Unfortunately I can't, so I have to settle for presenting the evidence and see if anyone has any better ideas.

First up, money supply growth shot up in November, even on a seasonally adjusted basis (log monthly changes, seasonally adjusted):

Half of the growth was driven by a jump in demand deposits, which forms roughly 4/5ths of M1 (RM millions):

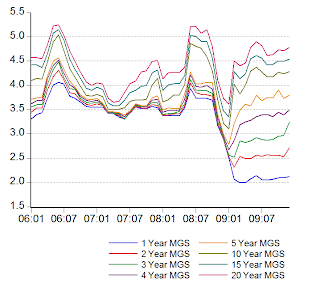

Average lending rates fell 6bp (no big deal), while loan growth fell to a seasonally adjusted 0.5% m-o-m. Here's where the story gets interesting. There was a net increase in public borrowing to the tune of RM6.5 billion (i.e. an increase in supply of government bonds outstanding) specifically for 3 year and 5 year maturities, but while 3 year MGS indicative yields did indeed go up (i.e. the price fell), yields fell at every other maturity:

As there were hardly any redemptions, that ought to indicate an increase in MGS demand sufficient to not only swallow the extra RM6.5 billion but also move prices up. On top of that, you have the competition from the massive Maxis IPO which set a record for equity fund raising in Malaysia (and incidentally, explains the surge in demand deposits)(RM millions):

To make things clear, we have a downward movement in MGS yields despite an increase in MGS supply, as well as a record IPO that mopped up tons of cash. Which means that there is an awful lot of investor demand for both, to the point where nearly RM18 billion in new securities were snapped up.

The question is: where did this demand come from?

It doesn't appear to be from foreign investors, unless they did a hit and run job - while the Ringgit had a wild month (by Ringgit standards), little of the funds appear to have stuck locally. Forex volumes, bank forex deposits and BNM's international reserves didn't change much for the month.

If it's local (or locally held foreign funds), then there ought to have been some kind of shift out of other assets into MGS and Maxis. That's harder to track, though by rights there ought to have been a drop in the KLCI pre-Maxis - there wasn't. There also ought to have been a shift from other deposit types (including interbank) into demand deposits - that didn't happen either, or at least not to the point where other deposits shrank.

I'm stuck with the rather unsatisfactory speculation that there's money from Singapore accounts coming back to Malaysia - but there's no way to "officially" substantiate this.

First up, money supply growth shot up in November, even on a seasonally adjusted basis (log monthly changes, seasonally adjusted):

Half of the growth was driven by a jump in demand deposits, which forms roughly 4/5ths of M1 (RM millions):

Average lending rates fell 6bp (no big deal), while loan growth fell to a seasonally adjusted 0.5% m-o-m. Here's where the story gets interesting. There was a net increase in public borrowing to the tune of RM6.5 billion (i.e. an increase in supply of government bonds outstanding) specifically for 3 year and 5 year maturities, but while 3 year MGS indicative yields did indeed go up (i.e. the price fell), yields fell at every other maturity:

As there were hardly any redemptions, that ought to indicate an increase in MGS demand sufficient to not only swallow the extra RM6.5 billion but also move prices up. On top of that, you have the competition from the massive Maxis IPO which set a record for equity fund raising in Malaysia (and incidentally, explains the surge in demand deposits)(RM millions):

To make things clear, we have a downward movement in MGS yields despite an increase in MGS supply, as well as a record IPO that mopped up tons of cash. Which means that there is an awful lot of investor demand for both, to the point where nearly RM18 billion in new securities were snapped up.

The question is: where did this demand come from?

It doesn't appear to be from foreign investors, unless they did a hit and run job - while the Ringgit had a wild month (by Ringgit standards), little of the funds appear to have stuck locally. Forex volumes, bank forex deposits and BNM's international reserves didn't change much for the month.

If it's local (or locally held foreign funds), then there ought to have been some kind of shift out of other assets into MGS and Maxis. That's harder to track, though by rights there ought to have been a drop in the KLCI pre-Maxis - there wasn't. There also ought to have been a shift from other deposit types (including interbank) into demand deposits - that didn't happen either, or at least not to the point where other deposits shrank.

I'm stuck with the rather unsatisfactory speculation that there's money from Singapore accounts coming back to Malaysia - but there's no way to "officially" substantiate this.

Labels:

interest rates,

loan growth,

Maxis,

MGS,

money supply

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

I'm Back...

Well, this has been a longer break from blogging than I wanted or planned for...but it's been a hectic month or so. Vacation, house cleaning, family, lots of drama in the last couple of weeks of the NFL's regular season etc, etc.

There's lots I want to talk about, which I will hopefully be able to cover in the next few days or so, work commitments permitting. In the meantime, Happy Belated New Year! And may 2010 be much more fruitful for you and yours.

There's lots I want to talk about, which I will hopefully be able to cover in the next few days or so, work commitments permitting. In the meantime, Happy Belated New Year! And may 2010 be much more fruitful for you and yours.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)