It’s a stylised fact and almost universally accepted that Malaysia is caught in a middle income trap. But a funny thing happened when I went looking for the evidence – it’ incredibly hard to find. And thinking about the issue made me more convinced that the whole idea is about as real as Hogwarts.

Taken at face value was does the term mean? Simply that a middle-income country stays a middle income country, and doesn’t make the leap into high income status. There’s also the notion of a poverty trap for countries; that low-income countries are unable or unwilling to make the necessary structural changes to achieve a growth “take-off” and start on the long road of development.

I hadn’t the time to try and track down the antecedents of both ideas, though they appear to have originated in the 1950s and 1960s (concurrent with the advent of development and growth economics) and formed the basis of large scale foreign aid to low income countries by the likes of the World Bank. In fact you could say that the whole raison d’être of development institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank is that countries need “help” – especially large scale, expensive “help” – to get going. I don’t want to get sidetracked into that particular debate, so I’ll just concentrate on Malaysia’s particular “problem”.

The reason why I haven’t been able to fully track these ideas down is that, despite a decent literature search, there’s an incredible lack of academic papers on the “trap” condition itself, as opposed to how to get out of one. That doesn’t make sense to me – where I’ve been able to find references, the idea of a “trap” is taken as a given, with lots of advice to aspiring countries on what to do to get out of one. There’s hardly anything empirical on what middle or low income “traps” actually are, much less if they actually exist. How you can define a policy path based on a particular problem, yet almost completely ignore the conditions and particularities of the problem itself, is beyond me.

There is however a consistent narrative that underscores the idea of a middle income trap and it goes something like this:

- Low income country begins by development through low wage manufacturing;

- Growth is driven by a shift in labour resources from low productivity agriculture to higher productivity manufacturing;

- Investment in the accumulation of capital relative to labour drives productivity improvements, both absolutely and relative to agriculture and mining;

- Rapid growth comes from both an increase in productivity and an increase in the quantity and quality of factors of production (investment in fixed and human capital; improvements in healthcare and diet cuts mortality rates and increases population levels);

- At some stage, diminishing returns sets in for capital, while population growth slows to a maintenance level;

- Since growth is now dependent solely on total factor productivity, rather than increases in the factors of production themselves, countries that lack the capability to improve productivity find growth potential limited by this constraint and remain stuck as middle income countries.

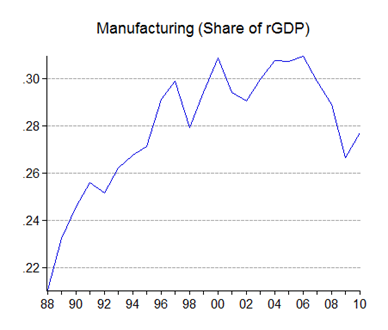

This narrative seems to describe Malaysia pretty well – we’ve nowhere near matched the record of development posted by the likes of Singapore or Korea for instance. There’s no doubt as well that manufacturing – especially export-oriented manufacturing – appears to have hit a wall:

But there’s a number of ways I can pull this argument apart. Let’s take the obvious first – for a middle income country to remain a middle income country, growth has to have stalled relative to the high income target. Here’s the raw data (GNI per capita; RM ‘000; 1970-2010):

Apart from three identifiable recessions (1985-87, 1996-2001, 2009-2010), growth has been steady, if not spectacular. The World Bank’s definition of high income only came into being around 1987 (click here for the data and history of the World Bank’s income definitions) – here’s the chart above as a ratio to that definition (GNI per capita in USD; ratio to World Bank High Income Level; 1987-2010):

You’ll notice that there’s a lot of movement here – the 1997 financial crisis caused a massive loss in relative welfare, as did this past recession, though not quite to the same degree. It took nearly five years for Malaysia to make up the ground lost in 1997, something which we’ve almost achieved in a year this time. The 2001 recession on the other hand was a mere speed bump.

But looking at the ratio above, there’s one thing you don’t see – stagnation. At almost no point, save in the early 1990s, could you reasonably point to and say “TRAP!” In fact, the recent record is actually pretty good, as we’ve almost covered a third of the distance to the high income threshold in the past decade alone. More formally, ADF and PP tests strongly reject the hypothesis that the ratio is stationary in levels.

Another way of looking at the same thing using different data is through the Penn World Tables, which has a few indicators measuring per capita GDP as a ratio to US per capita GDP (index levels; US=100; 1960-2007; G-K method;PWT ver6.3):

The picture here’s slightly different, but the conclusion’s the same – Malaysia’s per capita income is still gaining ground on that of developed economies. There’s only a few periods (pre-1968; 1980-86; 1997-2001) where you could say that Malaysia’s economy was “trapped” – otherwise, we’ve made continually progress. Again, formal tests point to non-stationarity.

Digression: It was interesting to look at the experience of the NIEs in this context – we’ve always been treated as poorer cousins to them, despite starting off on nearly the same footing. So I can’t resist inserting the following (log ratios to US GDP per capita; US=100):

Singapore and Hong Kong started off richer than Malaysia and maintained their lead. We started better off than Korea and Taiwan, but ended up behind because of two factors – poor growth pre-1970 and losing a lot of ground in the 1985-87 recession. More research required here obviously…and now back to the topic at hand.

The past, as they say, is prologue. Just because growth has rather inconveniently not stalled as per the “trap” hypothesis, doesn’t mean it can’t happen in the future. But even here, there’s more than enough grounds for rejecting it.

Recall the narrative of the middle income trap above – rapid factor accumulation plus higher productivity from the shift to manufacturing drive the initial growth phase out of low income status. As economies mature, factor accumulation slows and productivity gains become harder to achieve, “trapping” countries who can’t make the transition to higher value added manufacturing.

The first and very obvious shortcoming here is that this narrative essentially recognises only one path to development – that of industrialisation. But looking at the milieu of high income economies today, it’s obvious that there’s more than one way to skin this particular cat. Of the East Asian economies to make the full transition to industrialisation, I think it’s fair to say that only Korea and Japan have followed that road. Taiwan’s more of a mixed economy, and Hong Kong and Singapore have thrived on services. Europe’s experience is similar – for every Germany, there’s a Norway or Switzerland.

If we look at development policies, again there’s considerable heterogeneity. Japan and Korea followed an almost socialist style industrial policy, with Hong Kong’s laissez faire economy diametrically opposite. Singapore’s policies falls somewhere in between with an emphasis on pragmatism, and you could say that Taiwan’s policy with respect to development to be one of benign neglect. Yet all these economies managed to make the leap to high income status. This suggests that there’s the individual structure of the economies in question matters – and means that there’s no single “answer”.

Malaysia’s economy, need I point out, is pretty diverse. While export oriented manufacturing carried the initial brunt of development (from the 1980s onwards), we’ve continued to maintain a sizeable primary sector and now have a burgeoning services sector:

Focusing development efforts and investment on the latter (where measured productivity can be higher than in manufacturing) is likely to produce greater benefits than trying to counteract a trap that doesn’t exist.

Lastly, and the biggest reason why I reject the notion of Malaysia’s middle income trap, is that we’re not past the factor accumulation stage. Malaysia’s demographics are highly supportive of future per capita income growth. Birth rates have already fallen below replacement levels, yet we have a big cohort in the school years that will raise the ratio of the labour force to the population. Any investment made to raise productive capacity or factor productivity will produce considerable dividends down the road. We’re about to experience a baby-boomer induced economic growth phase on par with that experienced by developed economies in the post-WWII era.

Mark my words: fifty years from now, people will look back and see these next 2-3 decades as Malaysia’s golden era. While the ETP and NEM will probably get the credit, this is a structural transformation that’s been years in the making.

Technical Notes:

- GDP and GNI data from the Economic Planning Unit of the PM’s Dept.

- World Bank income data from the World Bank

- International per capita GDP data from the Penn World Tables

Because its a trap we're on a do or die mission.Certain "shocking" decisions and action needs to be taken.

ReplyDeleteThus direct nego contracts and landgrabs.Enablers to make certain projects viable is a must too.And government and GLCs must drive the investments.

Of course if we are not trapped things will have to be done in proper manner.So,sorry Sir. .u r talking nonsense.We are trapped and in the headlight of an onrushing MRT

Hishamh,

ReplyDeleteAgree with your analysis on the postive demographic effect on Malaysia's economic growth.

However, you have not touched on the serious issue of brain drain in Malaysia. Despite having an advantage in terms of population growth and demographic profile over country like Singapore, we are losing a big number of our brightest and high pontential citizens who go overseas to contribute to other economies to the extent of even competing against ours.

Your thoughts please?

@Rodger

ReplyDeleteThanks for the links mate, interesting reading. I'm not advocating a single route towards development - note that my charts show relative shares in GDP, not growth. There's scope for a further drop in manufacturing share without necessarily jeopordising our manufacturing base. And looking around there's still ample scope for growth in services (not just finance).

@anon

While the brain drain looks big in actual numbers, it's not that big in terms of the marginal loss of people per year. So I'm not too worried about it, especially since higher growth and higher per capita incomes will inevitably attract some back in the future. The ability to make money papers over a whole lot of other faults...

This post of yours is precise...in terms that it sets the other end of the judgement scale of Malaysian economic outlook. The realization of Malaysia's middle-income trap is a notion which has been regurgitated to death and its refreshing to see a fresh take backed up with some opposing evidence. Yet, the conclusions here seem to be substituting an overly negative view with an overly optimistic one.

ReplyDeleteI agree with all your points that highlight 'holes' in the middle income trap theory, and indeed most of your evidence is irrefutable. However i believe your evidence certifies that Malaysia's middle income trap is not as profound as a lot of economic analysts seems to make out (@ anonymous).

Yet, this is not to say that Malaysia being caught in a middle income trap is the stuff of fantasy. A main point which you fail to address is that, apart from the numerical calculation of a middle-income trap, is the factors pertaining to HDI, specifically Malaysia's 'Brain Drain' which acts as a massive withdrawal to the economy as well as leaving a bleak scope for the future. Furthermore, your usage of Nominal GNI figures is limited as it does not take into account the extensive rise to the cost of living (as well as rising commodity prices). Rising costs are so substantial that "Within the next 5 years, it is expected that Kuala Lumpur will be as costly to live as London" (quoted from Global Innovation Index 2011). This will also have disastrous implications on Malaysia's ability to attract FDI, arguably an economic necessity in order to rise to a high-income level.

Anyway, my main thoughts were on your "incredibly hard to find", thought i could assist:

-http://www.sti.or.th/sea-eu-net/form/Malaysia%20Country%20Profile%20draft%202011-05-26.pdf

-http://www.neac.gov.my/files/Malaysia_Economic_Monitor-Brain_Drain.pdf

-http://www.globalinnovationindex.org/gii/GII%20COMPLETE_PRINTWEB.pdf

Here's a few statistical analysis papers i had on file that speak specifically on current information pertaining to Malaysia's middle-income trap.

Hope to hear some feedback :)

Product angle: http://is.gd/rz33hl

ReplyDeleteStill looking for services angle...

What worries me is this:

We have commodities, manufacturing, oil and services.

Commodities is holding its own but it is worked by foreigners; if Indons, their economy is up and twenty percent who would have come here have decided to stay back so that's also a specter ahead. And since owned by a few, what reason have the estate owners to share their incomes with the locals who didn't work on them? Taxes via government as income dispenser? Another debate.

Next, manufacturing is hollowing out because other cheaper places are up all at the same time and because we had maxed at quasi-industrialization phase only so we are at best today only OEM and not ODM. So how to go beyond that? HK and Sg were manufacturing bases. They're not today even when their brain-pool is bigger.

In fact, it can be eye-opening to take a drive into all the industrial zones and just see what actually is happening inside them to get a better feel of the conclusions from charts.

Next, oil is sunset so the price will go up, giving a nice rush and then the bottom will be pulled away when it dries up; the day we become a net oil importer, our power plants will demand more tariff in order to survive; that impact needs to be factored, perhaps with other things like purchasing-power parities, inflation, and competitiveness.

i also have a problem with services because i can't figure out how the eighty percent of the workforce with only an SPM sijil can raise their productivity and earn more income beyond their salary scales.

Say they're not in banking or civil service. Where else? Nurses in private hospitals earning good income from medical tourism? How small is that on a 'per capita basis' which is the central unit of measure in the entire argument?

Allow me to make perhaps an error here: 'per capita basis' averages aggregates and hides lumpiness; a lot of wealth is held by a few under corporation banners which have been out-flowing funds lately. If a govt has to keep announcing the same projects as FDI, one can only conclude DDIs are few where real value is to be created, and FDIs have also been few and that is immensely troubling; for instance, say Arab money is nulled in Iskandar and the Jln Tun Razak financial hub; how will these projects look immediately?

So my concern is the diversity/heterogeneity factor is not strong enough where one element can compensate for the others and this feature the charts don't depict.

We don't have an amalgam of abilities led tenaciously by contextual intelligence with a pragmatic global spread.

Just being a pain in the butt, but you do realize that you don't need the ADF to say it's not stationary, don't you?

ReplyDeleteExcellent post bro hishamh..

ReplyDeleteA very pertinent question indeed.

On services side believe we're still on the cheap side of things, being cheap is ok if you got the numbers and the language skills to compete like India or Philippines.

To me I would prefer if we continue being "a Middle Income country" but with 80% of the country as the Middle Income, instead of a High Per capita numbers but a very large gap between the 2 ends of the spectrum

Hi Ski,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the links, but those papers are like those I’m complaining about – they talk of a middle income trap, yet do next to nothing to prove it.

Secondly, the problem of brain drain is serious, but not in the context I’m talking about here. Consider this – Malaysia’s brain drain has been going on for decades and has accelerated in the last ten years. Yet, this has hardly put a dent in Malaysia’s gains in income per capita. Will it have an effect down the road? Certainly, but not to the extent of derailing the demographic transition phase we’re about to enter. To do that, the loss of human capital needs to be far, far greater.

The World Bank report on brain drain was poorly done – it seems written more to shock and get attention rather than a rigorous treatment of the problem (the survey was a bad joke and should never have been attempted). The economic costs of brain drain have even been challenged from within the organisation. The question is: how much of Malaysia’s brain drain stems from our special circumstances, and how much from the “normal” immigration of talent from developing to developed countries? Globally the number one reason for immigration of high value human capital is economic. But that suggests that with time, economic growth and development in Malaysia will make it increasingly attractive for our diaspora to come back – and to attract talent from poorer countries in the region.

The latter maybe an idea that Talent Corp should be pursuing more vigorously instead of trying to get Malaysians to come back, as I’ll lay odds we’d have better chances of success. After all, isn’t that what Singapore’s been doing to us all these years?

The issue of brain drain is avery subjective issue. The argument Malaysia is doomed thanks to some PhD holders leaving Malaysia is unclear..is there any correlation between a country's growth with brain drain?Last time I red Australia caught 5 Malaysian with drugs, are these the brain drain you're talking about?The phillipine/indonesia have massive brain drain that repatriate foregn exchange to their home countries...so what is te effect of brain drain on Malaysia...?which category...

ReplyDeleteThe brain drain who fled to singapore are not talents, they migrated there for better pay, most are not involved in RnD and are mere cheap engineers and end up as RnD assistabts who wash test tubes.If not, why are Sinapreans despising the Malaysian foreign talents who are competing with them for HDB flats/jobs/school placements..most of these Malaysian PRs will eventually flee Singapore due to the high cost of living...true there are talents like Olivia Luma nd founder of Hyflux, but what is done is done.

We have 28 million people whom we can nurture and develop and we have a good education system despite what people say. I have seen technicians and a documentation engineer promoted to senior engineer and regionalQuality manager respectively as our US corporate heads see their potential and perseverance and willing train them and they do not speak Mandarin or impeccable Queen engrish.Imean even the Japanese and Italian engineer si met do not speak proper english but we do not see any issue..

I always doubt the figures that 80% of our workforce is SPm holders, we have 12 million workforce, can someone give me exact statistics how many are exactly SPM and even college educated.none can provide the answer,its just hearsay , as a baby boomer generation, most of my classmates are degree graduates and at least have a diploma,even my relatives are pursuing education in some way..certificates,diploma etc.Even if we look around us, we have many colleges/universities churning out graduates and most of us us haveworked outside our fields, I worked in marketing before and I got an process engineer job at a US/German semicon plant..we are working hard to build our future.

hishamh,I like your article, it may not be 100% true it is one of the few good news about our future around on the net....for 10 yers I read stuff in alternative news on how our country is doomed and gloomed due to nitty gritty issue and we are seeing countris with high speed trains and better public transport and people who queue going up in flames.

Walla, good points as always. I've actually read that paper you linked to in prepping this post. As you've no doubt noticed, there's a distinct paucity of other good sources on the subject.

ReplyDeleteHere's some food for thought:

1. Interesting factoid - we're short of foreign workers in plantations because wages are actually higher in Indonesia.

2. One fine day I'm going to a post on the myth of Malaysia's loss of competitiveness :). Consider that after a decade of double digit wage inflation, China's cost advantage is nearly gone. Vietnam and Indonesia are cheaper, but they don't have the institutions or the infrastructure to scale up yet. Also consider that the old view of mercantilist trade competition doesn't really apply here in East Asia - we're part of a long supply chain, and not necessarily competing with each other. I think at this stage, we're in a short term stable equilibrium with respect to manufacturing competitiveness and a 5-10 year window of opportunity to go up the value chain before the others start catching up.

Digression: with all the angst over the hollowing out of US industry, it's interesting to note that US industrial output has been increasing steadily over the decades. Implication - increasing productivity means stagnant job creation relative to output. Say we do become more innovative and add higher value to manufacturing? We'll need to handle the excess labour somehow, and services fits the bill.

3. Most of our power plants are gas-fired, not oil-fired, and NG reserves will last 50-60 years more than oil. In any case, I've always favoured a tax on petrol instead of the current subsidy.

4. The essence of what I'm pointing out in this post is that productivity gains aren't strictly necessary to register the required increase in per capita income. We're still at the stage where adding human capital is enough to raise output. A rising cost level and an appreciating currency will do the rest. But there will be a divergence here - costs of goods will become cheaper relative to incomes, but costs of services will need to accelerate. Material sufficiency will be easier to achieve, but quality of life will become a more pressing issue. But that's a problem endemic to all high income economies.

5. Another funny factoid I found while doing the literature search on this post - economic growth causes investment, not the other way around. Something on my future agenda to prove or disprove for Malaysia.

But you've pointed out the biggest fly in the ointment here - how do we ensure that the gains in income will be shared equitably? That's my biggest worry, the distributional issue between labour and capital. One way would be to impose capital gains taxes, but that would reduce business investment. Another option is to strengthen labour laws, but that introduces rigidities into the labour market. Third possibility is profit sharing remuneration schemes, but I'm struggling to figure out how to do this in the context of SMEs and non-listed companies. Fourth way - make everyone a capitalist (savings channeled into higher yield securities rather than low paying bank deposits), which has some promise as equity participation is still low. But this would not overcome the problem of initial endowments (rich get richer etc) and inequality. We'll probably need to look at a combination of these measures, but it's a pretty problem to be sure.

Hafiz,

ReplyDeleteIf I just said take my word for it, would anyone believe me?

In any case, it's always wise to check, especially with ratios (which by definition ought to be stationary, especially if you have a long enough time series). Besides, it only took a couple of minutes to do :)

Bro satD,

ReplyDeleteAgreed. Unfortunately reality beckons. We'll probably be lounging around thirty years from now, telling each other, remember the old days when roti canai was RM1? And many people could afford live-in maids? :D

@anon 9.56

ReplyDeleteSadly, the figure for educational attainment sounds about right to me - though you have to factor in the differences between age groups. The older generations have a lower ratio of degree holders, which brings down the average for the whole population. You can also get enrollment and graduation rates on Malaysia compiled by the World Bank here. It's not pleasant reading.

We're making progress especially with the expansion of private tertiary institutions in the past decade, but even if we doubled student capacity today it would be barely enough for my taste. The new emphasis on vocational education can't be implemented soon enough in my view.

thanks for the worldbank data....never knew such tool exist on the net!!!

ReplyDeleteI admit, the tertiary/college education penetration is quite low...does this indicate income dispaarity as the poorer ditch hopes of higher education?

I agree we need ramp up vocational education..the current ones are ridicuked as teaching the students to sell goreng pisang..we must try to change that.

@anon

ReplyDeleteI don't think it's a question of the poor ignoring or rejecting education, as primary and secondary enrollment and graduation rates are quite good. Remember though, every year thousands are rejected from public university places because there just aren't enough to go around.

It's a capacity problem of both hard and soft infrastructure - not enough institutions and classes, and not enough qualified lecturers and professors.

We are guiding ourselves with the wrong benchmarks cos we're advised by the American consultants.We have to use better models by reference to Korea,Taiwan or even India & China.They are developing by innovation,hard work and attention to cost.

ReplyDeletePemandu's Jalanomics is focussed on replicating Dubai,S'pore etc..and in the process getting "quick wins" through property play & temporary stimulus of Mega Projects.Capex is not scrutinised thus creating waste and ineffectual projects.

There are pockets of creativity thats not nurtured.For instance there's Joomla developers who are earning good money doing tools for the global market.There are also freelance consultants providing advisories to the big construction outfits in S'pore,Indonesia and Mid East.In short,we have lots of talents.But Msia's addiction to "sponsored" political businesses will forever make it unattractive for these guys to ply their trade here.

Maybe economics is complex..but in my honest opinion as long as the fundamentals of cost and innovation is not a focus,we will not account for much.Even a matter as simple as PPSMI has been convoluted at the expense of our students.

To conclude...any nation where the bulk of leaders & GLCs top managers are History grads and accountant will not have that drive towards competitiveness & innovation.

Paying a CEO 200-1500 times an entry level position salary is a clear symbol of a greedy culture that will sacrifice the future.

Lets hv new benchmarks & processes modeled to the creative nation that we should emulate.

I don’t think it is a myth, there is a shift of wealth from West to East and make the world economy more balance due to better education and lower wages, and we ride on this, it also helps when the Western capitalist not willing to put all their egg into one basket. I would say in the medium term, we could enjoy the growth but does this improve the common man living standard, I don’t know.

ReplyDeleteRead anon “I worked in marketing before and I got an process engineer job at a US/German semicon plant..we are working hard to build our future.” but I want to ask, whose future and what future? You are not working in a local industry (not oem of couse) that produce a Malaysian product that help to add sizeable values into our economies, and please, knowing Mandarin and English has nothing much to do with the aspire to create our own product and industry, it is just the prerequisite skill at this point of time to suit our economies that rely oon FDI and their manufacturing set up in Malaysia.

About brain drain, look at how China and Taiwan create their own brand (or own industry): Asus, Acer, Zte, Huawei, Baidu, HTC…..most of them are local brain with Western education, and I think this is not far off from what the Japanese and Korean is doing right?

I am not sure which country is our model of high income society, I presume we wish to emulate countries like Japan, Korea and Taiwan, my point is what have we done and what shall we do to get out of this ‘trap’ and become on of them?

Hi Hisham,

ReplyDeleteYour right about the Middle Income Trap not having a theory - that's why it has not really caught on in academia.

The World Bank and ADB though have a lot to say about it.

If your familiar with growth economics - a lot of this becomes clear.

The key question is "what growth rates are appropriate?". This of course is a political question. As you correctly pointed out, we have been growing but at a slower rate - and this is not politically acceptable.

But there are other more important cause for concern. Human capital and ability to innovate are key to long term sustainable growth. Here Malaysia is falling behind despite huge investment in education.

I have a summary of what is ailing Malaysia in this article. http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2011/08/22/malaysia-%E2%80%93-a-simple-institutional-analysis/

In addition to the works I've cited in my article on institutions, you may be interested in these works:

ReplyDeleteADB, Asia 2050, 2011; WB, East Asian Renaissance , 2007; Imbs and Wacziarg, Stages of diversification, 2003; Kenichi Ohno Middle Income Trap, 2009.

The key issue is not so much the trap but whether we can restructure the economy to a more competitive model - raising competency and contestability.

Keep up your wonderful postings.

Hi Greg,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the links.

I don't question the need for upgrading our software and hardware, but I do think that framing the problem in terms of a middle income trap risks an inappropriate policy response *cough* high income status *cough*. High income on its own is no panacea, and when we achieve that target (as I'm confident we will) yet with people's perceptions of things not having changed much, the tension between raised expectations (as Idris Jala puts it - "everybody will be rich") and actual realisation will be a political and social problem down the road.

Hi HishamH

ReplyDeletevery interesting view. good that i have found your blog, better late than never - a colorful view of Malaysian economy indeed.

hope to catch you for TEh Tarik some time when im in KL...

Nizam

ed DOT precise AT gmail

Agree fully with you hisham.

ReplyDeleteIn economic theory, increased incomes (welfare) is an organic process, as society learns to better deploy its productive resources.

Malaysia has serious issues with allocation of resources. It continues to be top down. Hence my disagreement with your article on East Asia Forum.

The government should retreat or take a hands off approach in deciding what "projects" contribute to growth. It should let the private sector do it.

While selective state intervention is necessary to drive a poor country to higher income levels, it cannot play this role when it moves closer to the frontiers of technology - i.e. state is good for catching up but not leading. This relies solely in the creative process of individuals.

I don't see how ETP can facilitate this. My bigger problem as you would realise, is this obsession with ensuring Bumiputera entrepreneurs must succeed.

The government is conflating two separate issues - efficiency and distribution. This should be addressed through separate instruments.

Greg,

ReplyDeleteI've only just seen my own article, so forgive the lack of reply.

I think the difficulty many are having with the government's programs is that there's such a smorgasbord of acronyms that there's confusion as to which program is supposed to do what. Hell, I've been to a few of PEMANDU's open days an presentations, and I'm only just beginning to understand what they're trying to do.

The ETP for instance is only intended to ensure the implementation and achievement of the investment targets identified under the NEM. Institutional reform on the other hand comes under the GTP, while structural reforms come under the new Strategic Reform Initiatives (SRIs) and distributional issues under the 10th Malaysia Plan.

We don't hear as much about the GTP compared to the ETP - I hear less progress is being made here due to vested interests (read: civil servant rice bowls). Much of the GTP is concerned with improving public sector service delivery and legal reform, but it also involves culling ineffective projects and initiatives (you can just imagine the resistance to this). The SRI's of course are spanking new, while the 10MP is nothing more than spending priorities.

Maybe the government needs to do a better job communicating progress on these other fronts too, not just the ETP. But then, since measuring progress here is much harder than the easy-to-sell investment numbers under the ETP, I'm sure there's a political decision not to.

I'm not sure I agree that the NEM/ETP/GTP are "more of the same" top-down management of development. I know a number of people who were involved in the formulation of the ETP/GTP projects and the former, within the broad confines of the sectors identified under the NEM (none of which I disagree with), was definitely private sector driven. In fact the complaint was it might have been too much private sector driven.

Hi Hisham,

ReplyDeletePrivate sector driven...hmmm which private sector.

A point on government as facilitators and government as managers (the Malaysia Inc. model). The ETP is a continuation of the Malaysia Inc. model where the government acts as a manager model.

If we agree that the private sector should take the lead, why does the government need to "decide" who gets "what" project.

Allow the private sector to decide which projects is feasible. If more than one company wants to go into a particular sector or undertake a project - go ahead. They should bear their own risks.

Why the need for EPPs? Why the need to have labs to discuss what areas are for new growth? This can lead and I believe have led to collusion. Certain companies will get certain project - of course in Malaysia's very own transparent manner.

Look at how the GLCs continue to intervene in the workings of the market. There is now less scrutiny because it is all centralised within PEMANDU, which is within the Prime Minister's Department, and the Prime Minister who also happens to be the Finance Minister.

On another note, here is the survey that was used in the Brain Drain report. You can contact the author if you want to.

http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2011/09/21/brain-drain-in-malaysia/

Cheers

Greg

Greg,

ReplyDeleteWhile I won't disagree with you with respect to the mega projects like the MRT and KLFID (which are about as transparent as mud), I can't actually recall many EPPs being undertaken by GLCs. Certainly the ones that I work with aren't involved in any big way.

The feedback that I've gotten from participants in the labs have been "good" in a perverse kind of way - the debates and arguments were apparently highly contentious and confrontational.

A second point is that the EPPs are in no way "public" sector projects or even "public-private" partnerships, except where GLCs are involved. The risks continue to lie with the investor here. I suspect many of the investments so far announced actually predate the ETP, and were put forth mainly for the chance of faster approvals and prestige purposes.

Hi Hisham,

ReplyDeleteThis is a very late reply. Been finishing up my thesis. Happy New Year by the way.

You noted that that EPPs are in no way public owned (agreed) or even PPP except when GLC owned (not so sure).

Assuming your correct, this would bring many of "government expeditures" off-budget, don't you think so?

Also, appreciate your opinion on the multi-layer "fixers" - PEMANDU, PEMUDAH, MIDA (One stop investment centre) - basically all of these are about reducing transaction cost (would you agree), yet more institutions/organisations are created to basically do the same thing.

Hence the ETP is really a "fixer" as the REFSA papers argue.

Also, in an earlier comment, you noted that the GTP is not moving (where the actual instituional bottlenecks are).

Hence, do you think transaction costs can actually be lowered if nothing happens in the GTP?

Thanks

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteOur GNI and GDP growth per capita certainly looks impressive.

ReplyDeleteNonetheless aggregates don't tell an awful lot about distribution. So I very much agree with @walla points.

1) The slack in manufacturing was well picked up by commodities super bull market in the past decade(minus some violent price correction in 2009 and 2011)

2) IMO,the state of manufacturing is much worse than reflected in the drop as share of GDP&export. General observation is that for every engineer there is probably a van load(or maybe even bus)of foreign workers.

3) Except for rubber tapping, I know of no Malaysians of my age who are doing non supervisory job in plantations.

4) It would be helpful also to have the figures for services as percentage GDP&Export. As well as population details of different sector.

The tremendous growth in the service sector was probably a consequence of the need to absorb more and more Malaysians moving away from goods/crops producing sector. I just hope that the service sector is not overly reliant on the windfall from commodities.

"fifty years from now, people will look back and see these next 2-3 decades as Malaysia’s golden era"

Would only agree in a the case of a prolong Western deflation balanced by Eastern/South economic growth.

If US/Europe knocked the world into a global depression, then we will be very hard hit(not as hard as other countries though). Meaning a crash in commodity price and manufactured goods demand.

Even if we can generate internal demand, how are we going to reintegrate enough number of Malaysians into jobs that produce goods/crops remains to be seen.

@Greg,

ReplyDeleteI don't think it would be proper to say that we're looking at bringing govt expenditure off-budget - private sector investment is still private sector, irrespective of whether it's under govt aegis or not.

I agree that that PEMANDU is a "fixer", though not in the sense that the REFSA papers have insinuated. I think it's really a way to short circuit the govt machinery process (and turf battles), putting pressure directly on the civil service beyond what could be achieved at the ministerial level.

Is that good or bad, I'll leave for the political scientists. But I'm reminded in this instance of "Yes Minister" (if you've ever seen it). Political appointees are subject to "capture" by permanent officials. As much as that was satire, I suspect it comes with more than a grain of truth.

Remember that PEMANDU is repsonsible for more than just the ETP, but also implementation of the GTP, NEM and 10MP. Their remit also goes beyond the more narrowly defined roles of each ministry.

I don't think I said there was no progress on the GTP, more that there was considerable internal resistance to it.

@Oi Mun

ReplyDelete1) In terms of growth, I agree. But apart from the sharp and deep drop caused by the recession, manufacturing has now recovered to pre-recession levels and then some.

2) I think there's a slow move away from export-oriented manufacturing towards domestic - but it's a slow process.

3) My brother-in-law's a padi farmer :)

4) Services share of GDP is actually available and announced in the quarterly national accounts report (from which I derived the chart in the post). The services share of exports has been for the last few years recorded a small surplus, primarily from tourism. Labour force for each sector is available via EPU or from DOS (second drop down list, item 12).

Gains in services were pretty much across the board and faster than any of the primary or secondary sectors. Of them all, I'd say only transport and storage sector might be particularly sensitive to commodities. Remember that when talking about real GDP, price changes are stripped out.

"Would only agree in a the case of a prolong Western deflation balanced by Eastern/South economic growth."

You're missing the point of that part of my post. It's pure mathematics - our GDP per capita growth has GDP as the numerator and population as the denominator. Population growth is dropping fast, but current labour force growth is dependent on population growth 20 years ago when it was a lot faster. Ergo, GDP per capita must increase faster than GDP during this transitional period, irrespective of economic conditions here or abroad.

Since we're also looking at a ratio (GDP/GNI per capita relative to the World Bank's high income threshold, or equivalently the US standard of living), not a level, these gains would likely occur anyway, even if the global economy tanks.

As to how to absorb all these new entrants into the labour force, crudely speaking demand creates its own supply - people need to eat, they need shelter, they need clothes and all the other myriad things that come with modern life - and someone has to supply all these items.

While I don't believe in the absolute applicability of Say's Law, there's a certain truth in it.

And if you don't believe in that, there's always the ETP, which funnily enough aims to create just enough jobs to fulfill the expected number of new entrants to the labour force in 2020.

Hishamh,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the linkd. I must learn to build some charts.

Hopefully the downturn of our manufacturing has bottom out.

Understand that your post is about debunking on some vague mainstream assertions. So far figures for income growth Asean and BRICS should be outgrowing global benchmarks.

Instead of preoccupying with main aggregates and speaking as a layman I am just of the opinion that we could probably be more focused on domestic structural issues.

Dont know about Thailand figures. But their balance of manufacturing, agriculture, service and natural gas looks pretty resilient from the outside. (barring political/natural disaster)

I am sure people can adapt. I am just concern of how the transition would be.

Hi Hisham,

ReplyDeleteYes Minister is one of my favourite. And there is now Hallow Man.

If you have the time, look up Mustaq Khan on governance and economic growth.

http://www.soas.ac.uk/staff/staff31246.php

HE has some interesting views on how to square the politics and economics of growth.

ps: When you have the time, appreciate if you could comment on all of the REFSA articles on PEMANDU.

Cheers

Greg

Greg,

ReplyDeleteNot much to comment on the Refsa papers - I find it hard to take them seriously.

Haha, a bunch of idiots talking about economics. let's hope no one ever see this. they might think Malaysia is caught in "sub-par intelligence trap".

ReplyDeleteguys, maybe the "sub-par intelligence trap" (SPIT) coupled with the "above-average confidence" (AAC) is the reason for our "mid-income trap". (MIT)

I remember i went to a lecture by Solow in HBS, he mentioned this matrix:

z*SPIT*AAC=MIT

*ps: z=ignorance of self-stupidity

i love to read short comment, because they denote a concept of saying as much thing as possible with so little words, but there is also some short comment that basically saying nothing not matter how we read it, as indicate by one here. of course we cant blame solow and hba for failing to enlighten an uninspired mind that is incapable of breaking free of it’s own hubris to see others’ perspective. anyway, hopefully in his next comment he’ll actually have an argument to offer about something rather than these random musings that have seemingly nothing to do with the topic at hand.

ReplyDeletePersonally, I think that in a world where labour has become highly specialised and no one person can encompass the totality of knowledge in any given field of study, calling someone else an idiot says more about the character of the person making the comment than it does about the people being commented on.

ReplyDeleteHi Hishamh,

ReplyDeleteYour article is very stimulating and has a good angle. Recently, 3 economists from Asian Development Bank provided a working definition of "middle income trap" in a working paper published in April 2012. According to that paper, Malaysia is in a middle income trap. A summary of that paper can be found in my post:

http://malaysianeconomy.wordpress.com/

Hi Teo,

DeleteYes, I read that paper when it came out. I also note that their definition of middle income trap is arbitrary. To me that's trying to get the data to fit the hypothesis, which isn't what I would call academically rigorous.

Some other pointers:

1. Note that Malaysia's growth has exceeded global growth nearly every year since independence, and is about on par with our peers.

2. Most TFP growth estimates are also about on par with our peers, and exceeds that of Singapore. Insofar as the trap hypothesis is a narrative about productivity, that suggests that we are not in one.

I do not think the definition is entirely arbitrary. Other things being equal, a middle income country should grow faster than a rich country, since there is more opportunity to learn from the leader and catch up. This means that a middle income country should close its gap relative to rich country, unless its economy is really in a bad shape. But, the real question is how fast is the gap closing. If the growth rate is only slightly higher than the rich world average, it could take literally decades for a country to graduate to high income status. Simply calling a country to be not in a middle income trap because it eventually will get out of it (but perhaps after decades) does not seem to be a good idea. That's why even if using median is somewhat arbitrary, I think the authors' criterion is still quite useful as a guide.

ReplyDeleteI don't think the middle income narrative is only about TFP either. Growth in per capita GDP depends not only on TFP but also on growth of capital per worker. If a country fails to move up value chain, growth of capital per worker could slow as there is lack of investment opportunity and growth of GDP per capita can therefore be slower, making the transition to high income status a much more delayed process.

The problem here is that their definition is not with reference to catch-up to the global technology frontier (e.g. catching up with the US, which is the way I approached the subject in this blog post), but from a sample of other middle income countries that have graduated to high income status.

DeleteThe underlying assumption would then be that the experience of these countries is "normal" and those who don't meet that standard are ipso facto "lagging". This is like taking the upper end of a distribution of outcomes and declaring it as the entire population - there is an inherent bias here (or if you prefer, a halo effect).

Second point is that there's also an underlying assumption that the sources of growth are entirely endogenous, which isn't true. The first wave of Asian rebuilding/industrialisation after WWII was partly driven by US spending on the cold war, the second wave by outward Japanese (and to a lesser extent, Taiwanese and Korean) investment in the wake of the exchange rate adjustment created by the Louvre Accord - all exogenous events. I could name a couple more, like China's 1993 devaluation that rendered everybody else uncompetitive at a stroke.

Looking at the data, it's fairly obvious that Malaysia's record matches that of the NIEs, except that we were badly affected in 1985-87 and in 1997-98, whereas Korea, Taiwan and Singapore were considerably less so. The former recession was especially damaging.

If the middle income trap is an economic "process" (whether you accord the blame on TFP or capital intensity), then one would expect a graduated response, not the sharply volatile movements around crisis points that we're seeing in the data.

Another point is that recoveries after financial crises are always slower than business cycle recessions, irrespective of the stage of development, which pretty much describes what Malaysia went through in the half decade after 1997-98.

So we have a serious identification problem here - how to distinguish between what underpins the trap hypothesis, and the exogenous events that have driven investment and output in Malaysia and the region.

If you look at the capital stock data (DOS has the time series available online), then it's fairly obvious that growth in the capital stock (and in capital intensity) has fallen off sharply post-1998.

But again, that presumes that investment before 1997 was endogenously driven and appropriate for our stage of development. That's something I don't accept - for one, the Japanese factor, and for another, the real estate bubbles we endured in the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s. Most of the drop in capital stock growth in the last decade came from falling investment growth in structures.

I worked in banking during the 1990s, and saw all this first hand - highly excessive credit growth, excessive money supply growth, real estate and stock market speculation, and of course the aftermath of all the above.

What I'm getting at here is that there are growth spurts and growth slowdowns, but I don't believe that there is a universal mechanism that explains why some countries succeed and some don't.

But thanks for the comments, you've given me something to look at over the next couple of weeks. I didn't have access to detailed data on the NIEs when I did this post last year, but I do now. It be interesting to map out the differences in the growth experience between those countries and Malaysia.