You might remember Global Financial Integrity’s report on illicit money flows early last year, where they reported Malaysia as being the fifth highest victim of uncategorised capital outflows in the last decade.

At the time, I partially validated their findings at least in terms of the trade mispricing channel – wildly different reported values for exports and imports between different trade partners.

So since I had a bit of time, and lots of curiosity, I decided to take a bit of a deeper look into the question of Malaysian trade mispricing, using the United Nations Commodities Trade database (Comtrade), which carries data on both imports and exports as reported by nearly every trading nation (Taiwan not included).

Did I find capital outflows? Yes, I did, and on a scale that conforms to the GFI report.

But the surprising thing was that I also found evidence of substantial capital inflows as well, even after correcting for estimated shipping costs. In fact, for the past decade, capital inflows actually outweigh capital outflows (at least, if I got the flows right).

A more in depth explanation is called for here. How do you decide if money is leaving or entering the country? Let’s say you declare US$X amount of imports, but your exporter in another country declares he sent US$(X-Y) value of goods. While imports are valued at US$X, you actually pay US$(X-Y). That US$Y represents the money leaving the country.

Another way to do this is via transfer pricing. You declare US$X in terms of export value to your foreign affiliate, but he in turn declares receiving US($X+Y). Since you’re under-declaring your sale value locally, you make less “profit” and pay less corporate tax. Alternatively, your foreign affiliate is over-declaring his cost of goods, thus making less profit, and paying less corporate tax.

Notice in the latter case that it’s not necessarily money leaving the country, rather a deliberate choice of tax jurisdiction depending on which one is lower, or where enforcement is more lax.

At least, that’s how I think it goes. If anybody can think of a flaw in my logic, please let me know.

So if I’m right, local declared imports > foreign declared exports and local declared exports < foreign declared imports means either money actually leaving the country, or a reduction in corporate tax liability locally.

But that means the opposite must also be true: local declared imports < foreign declared exports or local declared exports > foreign declared imports, must mean money flowing into the country, or an increase in corporate tax liability here as opposed to elsewhere.

So here’s the raw numbers (all in USD):

| Exports | Imports | |||

| Malaysia | World | Malaysia | World | |

| 2000 | 196.5 | 112.8 | 162.6 | 77.3 |

| 2001 | 176.0 | 104.7 | 146.2 | 68.7 |

| 2002 | 188.1 | 110.8 | 157.3 | 73.3 |

| 2003 | 209.4 | 127.5 | 164.9 | 82.1 |

| 2004 | 253.3 | 152.0 | 210.3 | 93.7 |

| 2005 | 283.2 | 169.3 | 228.6 | 102.7 |

| 2006 | 321.3 | 192.6 | 262.3 | 120.5 |

| 2007 | 351.9 | 214.7 | 292.2 | 135.6 |

| 2008 | 397.4 | 240.0 | 311.3 | 152.2 |

| 2009 | 314.4 | 191.7 | 247.2 | 123.9 |

| 2010 | 397.6 | 247.7 | 329.2 | 160.0 |

Graphically (USD millions):

Malaysia’s exports and imports are both systematically higher than that declared by our trade partners.

Could this be a problem at Customs or with the way DOS enumerates the data? It would seem so at first glance, but looking at some of the individual trade partners, a problem at our end should be ruled out.

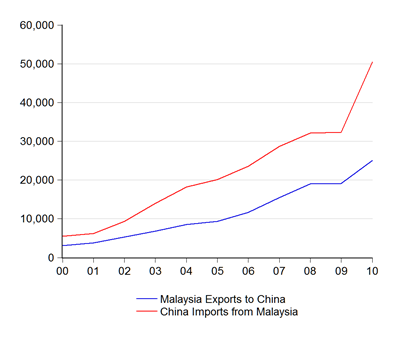

To illustrate, take these two examples:

In Japan’s case, the difference in Malaysian exports and Japanese reporting of imports from Malaysia can be largely attributed to CIF costs (which aren’t included in the export numbers). CIF by the way is carriage, insurance and freight – from my limited reading, these costs vary from between 4% to 15% depending on distance, risk, availability of shipping etc. Japan’s exports to Malaysia can also be attributed to CIF, though the CIF costs are higher (using more expensive Japanese freight? possibly).

With China however you see a huge difference. China is reporting massively more imports from Malaysia than Malaysia is reporting exports to China. On the other hand the difference in China exports/Malaysian imports can probably be put down to CIF costs…until 2007. The lines amazingly actually cross after that. Both these trends together indicate export receipts not brought home, or money actually leaving Malaysia, a net loss for us.

But you can see here it’s not a systemic problem at our own borders, and more a problem with specific trade partners.

But aside from the China example above, the aggregate numbers tell a different story – locally declared exports are greater than claimed imports overseas, while locally declared imports are also greater than claimed exports overseas. In effect the two problems indicate both inward and outward capital flows.

Taking into account CIF costs (I assume a flat 10%), here’s the net flow over the last ten years (RM millions):

The total amount from 2000-2010 is about +RM340 billion. Changing the assumption over CIF costs will change the numbers, but the overall view is still that of a positive net inflow.

I haven’t gone deeper into this to work out where the problems are with specific partners except for the major ones (surprise, surprise, we have a big capital deficit with Singapore), but that seems to be something worthwhile doing.

In the meantime…shall we start talking about illicit capital inflows?

Technical Notes:

All data from the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database

Why is there a "big capital deficit with Singapore"?

ReplyDeleteIs there something that you are not telling us?

Or could it be that a lot of Malaysians (individuals and corporates) are parking substantial funds in Singapore?

Ah, if only the legions of private bankers and wealth management firms in Singapore were to open their books to scrutiny by the Malaysian tax authorities!

Wishful thinking. I know.

Of course, most of this could be resolved very simply if the Malaysian Ringgit and the Singapore Dollar were on par, instead of 1 Singapore Dollar fetching 2.40 Malaysian Ringgit at your friendly money changers in Singapore's Raffles Place.

ReplyDeleteWhat this would do to Malaysia's competitiveness and to the whole pool of labour-intensive SMEs in the country is anybody's guess.

"...the legions of private bankers and wealth management firms in Singapore..."

ReplyDeleteNo, not them...think MNCs. These are trade related, not wealth related flows. But yes, a visit from the taxman - on both sides - is warranted.

"...most of this could be resolved very simply if the Malaysian Ringgit and the Singapore Dollar were on par..."

MAS uses the exchange rate (not interest rates) as its primary monetary policy tool. With Malaysia being Singapore's largest trading partner, the bottom line is that Singapore follows a deliberate policy of appreciating the SGD against the Ringgit. As long as they keep this policy, no matter how fundamentally strong the Ringgit becomes, the Sing dollar will be stronger.

That's a bit of an oxymoron, if you ask me.

ReplyDeleteWhat's stopping Bank Negara from adopting a deliberate policy of appreciating the MYR against the SGD?

How long can Malaysia rely on a "cheap" Ringgit and low-cost labour intensive industries to give a competitive edge to the economy?

Why is the government not biting the bullet and pushing through drastic economic restructuring, never mind short-term pains?

"What's stopping Bank Negara from adopting a deliberate policy of appreciating the MYR against the SGD?"

ReplyDeleteCommon sense. We have a fairly well diversified economy, which doesn't rely too much on trade (growth contribution from trade over the last decade is slightly negative). Singapore on the other hand lives and dies by trade. An exchange rate driven monetary policy makes sense for them, but not for us.

"How long can Malaysia rely on a "cheap" Ringgit and low-cost labour intensive industries to give a competitive edge to the economy?"

Believe it or not, we aren't. Haven't been for some time. At the very least, not since the Ringgit was floated in 2005. Most of our exports aren't sensitive to exchange rate movements, or to low cost labour. Blame it on globalisation.

Sir, you raise an interesting point.

ReplyDeleteThen how is it that Australia, which relies heavily on the export of commodities, has it's Dollar worth about 1.34 Singapore Dollars?

Surely, it should be the other way around - the Singapore Dollar should be worth more against it's Australian counterpart, given that Australia is a major trading partner of Singapore and the 2 countries have a free trade agreement in place.

Also, I don't get your argument that a weaker Malaysian Ringgit vis-a-vis the Singapore Dollar is beneficial for the Malaysian economy in the medium- and long-term.

Would there be less "temptation" for individuals and corporates to park their funds in Singapore if, say, the Malaysian Ringgit and Singapore Dollar were on par with each other?

Also, how long can Malaysia get away with being a low value-add low-cost economy where labour and assets are, to use a favourite phrase of my Singaporean friends ""cheep, cheep, cheep"?

There is already a documented flow of Malaysian talent to Singapore, due in part, I think, to the higher earning power in the citystate and the perception of it having a "stronger" currency with better policy and fiscal management.

I would suggest that you read the recent speeches made by Singapore Finance Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam in the Singapore Parliament this week with regard to their Budget 2012.

Much of what he said has direct relevance to Malaysia.

@Olek

ReplyDeleteThen how is it that Australia, which relies heavily on the export of commodities, has it's Dollar worth about 1.34 Singapore Dollars?

You're confusing the relative value with a currency's purchasing value. The value of the exchange rate between two currencies tells you precisely nothing. If the exchange value of a currency is a measure of its strength, then the Yen would be pretty weak, which is obviously not true.

Also, I don't get your argument that a weaker Malaysian Ringgit vis-a-vis the Singapore Dollar is beneficial for the Malaysian economy in the medium- and long-term.

That's not what I said. According to BNM, the Ringgit is fairly valued on a trade weighted basis, and my own models tell me the same thing. Singapore's currency is valued higher, simply because their stage of development is further along, and their demographic profile is more mature.

Would there be less "temptation" for individuals and corporates to park their funds in Singapore if, say, the Malaysian Ringgit and Singapore Dollar were on par with each other?

Again, there's no relation between a currency's absolute exchange value, and its relative purchasing value.

Also, how long can Malaysia get away with being a low value-add low-cost economy where labour and assets are, to use a favourite phrase of my Singaporean friends ""cheep, cheep, cheep"

The causality runs from income per capita to exchange rate, and not the other way around. Look up the Penn effect. Malaysia suffers a lower exchange value to the SGD not because of being a "low-cost" economy, but because of lower income per capita and a lower price level. And that has more to do with the labour force/population ratio (inversely, the population dependency ratio) then it does anything else.

There is already a documented flow of Malaysian talent to Singapore, due in part, I think, to the higher earning power in the citystate and the perception of it having a "stronger" currency with better policy and fiscal management.

Also true of Malaysian emigration to Australia and many other advanced economies. But that is again related to higher income per capita (higher price level and living standards) then anything else.

As Malaysia's income per capita rises (again, largely demographic in nature), you'll start seeing the trends reversing (try here and here).

Don't lose sight of the forest for the trees.

Sorry, missed the second link in the last paragraph:

ReplyDeletehttp://econsmalaysia.blogspot.com/2010/02/income-age-and-dependencies-malaysias.html