[When I first started this blog a year ago, I made a list of some of the things I wanted to talk about regarding the structure of the Malaysian economy. I had twelve items on that list, but in the past year I've only managed to cover five. This post starts off with one of those uncovered topics - one down, six to go! P.S. There will be two versions of this post. This first once presents a normative argument, with some backing data. The second post will be for the more statistically inclined]

Here's a few predictions about the future of Malaysia:

1. By 2020, the level of crime will have increased about 13%-14%, irrespective of the policies of the government (whichever one we will happen to have by then), or the level of enforcement.

2. Property and housing will be a very good long term investment.

3. We will still be considered a middle income country, but only just.

There's a common thread underlying these predictions - demographics. I got prompted to look at this from a few paragraphs in the introduction to

Freakonomics (crime in the US fell in the mid-1990s because of the impact of Roe vs Wade on legalised abortion two decades earlier), as well as rereading this fascinating old article from the

IMF's Finance and Development magazine. It's a stylized fact that a bigger working population relative to the population as a whole is associated with (I won't say "causes") higher per capita incomes.

A dynamic view of this relationship can be explained by the demographic transition model (the

Wikipedia article on this is pretty good - no, I haven't read any primary sources on this yet):

Stage 1: preindustrial society; population stable

Stage 2: better health care causes death rates to drop and improves infant survival; population growth

Stage 3: urbanisation, increasing incomes, and other factors cause the fertility rate to drop; population growth slows

Stage 4: industrial society; population again stable, but at a higher level

Stage 5: countries where the birth rate drops to low; population shrinks

There is therefore the potential for what's called the "demographic dividend", a transitory phase where a larger working population coupled with lower fertility rates means excess income that can be used for investment and asset accumulation. The IMF article further argues that there is a second dividend arising from a larger, wealthier old-age cohort who invest their retirement funds, thus further boosting the pool of funds available for investment.

In short, countries in stage 3 and stage 4 tend to have higher growth and then higher incomes, relative to those in earlier stages. The IMF article estimates that as much as 44% (about 1.9% p.a.) of South-East Asia's growth between 1970-2000 came from this transition.

This article makes an even more comprehensive argument that demographic change was behind the East Asia growth "miracle".

To illustrate, here's Thailand's population pyramids between 1965 and 2050 (from the IMF article):

So what's the point of all this?

Malaysia is actually the diamond in the rough (or if you prefer, the thorn among the roses). When other countries in the region began actively trying to restrict population growth after the 1960s, Malaysia only paid lip service to the idea then went the other direction with the 1984-85 National Population Policy. If you aren't old enough to remember this, the goal was to increase the population to 70 million by 2100 - with lots of accompanying jokes about encouraging polygamy, natch.

As a result, we are far behind the curve in getting into stage 3 of the demographic transition compared to our regional peers. To compare, here are the population pyramids for Singapore, Hong Kong, Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia in 1990:

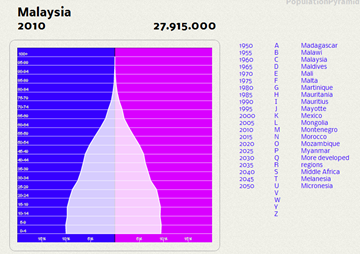

...and the same countries in 2010:

(All the above from

Nationmaster.com: you can find more population pyramids on the site, look under age distribution under each country page).

Note the substantial difference in age structure between the Asian Tigers and the other three countries shown here. Also, Malaysia appears to be behind even Indonesia in starting the stage 3 demographic transition.

Two other ways of looking at the same data is to use the median age of the population, and the dependency ratio, which is defined as the percentage of the population outside the 15-64 age bracket (using the same sample of countries):

Malaysia will have the same population median age in 2050, that Singapore had in 2000! This explains a lot of why Malaysia has lagged the Asian Tigers in growth - imagine a 2% disadvantage in per capita income growth every year, for a whole generation. On that basis, it's actually more surprising we are a middle-income country at all, as our population age profile is more typical of a stage 2 low-income economy.

The implication is also that Malaysia's growth potential over the next couple of decades is far higher than most of the region - apart from Indonesia, the rest of the economies in this (unscientific) sample will be subject to rapid population aging after about 2015. But the key to realizing that growth potential of course is putting in place the correct policies to take advantage of the demographic dividend when it comes.

Getting back to the predictions I made at the top of this post, the reasons why should be clear:

1. The level of crime will increase 13%-14%, simply because the supply of potential criminals will increase by the same portion (I'm assuming males in the 15-29 age bracket). The confidence interval for this would necessarily be large, as the other determinant of crime is the state of economy (and believe it or not, not enforcement).

2. Population growth in the working-age cohorts will increase demand for relatively scarce housing and residential land.

3. Based on some models I'm working with and the assumptions I'm making, I'm getting estimates of between 2023-2030 (when the median age will be between 28-30) when Malaysia will pass the middle-income barrier. That's when the current crop of youngsters will have entered the workforce and started earning and consuming (assuming of course, we manage to generate enough jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities for them).

Technical Notes:

1.

Demographic Transition, Wikipedia article

2.

Demographic Dividend, Wikipedia article

3.

"What is the Demographic Dividend", Lee, Ronald & Andrew Mason, Finance & Development Magazine, Sept 2006 Vol43 No3, International Monetary Fund

4.

"Demographic Dividend", Barker, JF, Online article, Population Growth & Migration website (2004)

5. Population pyramids from

Nationmaster.com

6. Global population data and estimates from the US Census Bureau's

International Data Base