The consensus is leaning towards another 25bp OPR hike (excerpt):

Economists expect rate hike next week

PETALING JAYA: Although Malaysia’s year-on-year (yoy) export growth of 21.9% to RM52.3bil in May fell below market expectations, economists are still positive on an interest rate increase next week…

…Bank Negara raised its key rate by 25 basis points to 2.5% in May – a normalisation process after rate cuts during the global downturn.

AmResearch senior economist Manokaran Mottain told StarBizWeek that although the numbers showed slower-than-expected-growth, it was still at respectable rate…

…Thus, Manokaran said the interest rate hike next week would likely to go on.

“But after July 8, I think there will be a pause pending on the development then,” he said.

Standard Chartered Bank economist Alvin Liew was quoted by Reuters as saying despite the slower exports growth in April and May trade data, these two months of data still pointed to a decent second-quarter economic performance…

…“As our expectations for a healthy recovery in first half of this year remains intact, we reiterate our view that the central bank is likely to continue normalising interest rates further to suit current economic conditions.

“We expect Bank Negara to hike rates by another 25 basis points at its July 8 policy meeting and thereafter keep the overnight policy rate on hold at 2.75% for the rest of the year, which is the normal rate for the OPR in 2010, in our view,” he said.

Like any good economist, I’m in two minds (or two hands) on whether continued “normalisation” of interest rates is called for. With growth likely to slow and external demand likely to fall off, we’re still faced with a substantial output gap, i.e. there’s still unutilised capacity in the economy, which means there won’t be much pressure on consumer prices in the near term. The relative strength of the MYR also means less inflationary pressure from imported inflation.

So what’s the case for continuing to raise interest rates? BNM’s concerns will be centred, to their credit, on asset markets, which has not been a particular focus of central banks until this past financial crisis. But before getting into that, what other indicators would matter?

First, inflation is pretty tame, so raising interest rates effectively mean also a rise in real interest rates:

…which is what BNM is aiming for. By raising the cost of borrowing, BNM is hoping to limit a build up of leverage and consumption that would raise consumer and asset-price inflation. Consumption indicators are up this year, such as loans (log monthly changes):

…but not to any great extent. Housing loans are a fairly big chunk of the increase (defying the increases in interest rates: more on this later), but other loans for asset purchases aren’t too troubling (log monthly changes):

…and working capital loans are growing at least as fast.

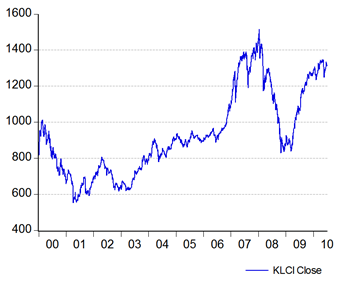

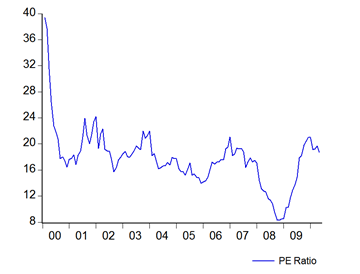

Turning to the asset markets, the FBM-KLCI has almost fully recovered to its 2007-2008 peaks, and you could argue that at these levels, the stock market is overvalued:

More solidly, house prices have started to pick up at the end of 2009 (log annual changes; 2000:100):

…but 3% per annum doesn’t exactly qualify us as an overheating property market. The only thing that stands out is prices of high-rises, which rose 8% in 4Q 2009, and apparently primarily in Penang. So what we’re looking at here is a potential limited market bubble confined to a small (but volatile) segment of property. Tightening monetary policy to keep a lid on this strikes me as using a hammer to swat a fly. The other aspect of this is that based on the limited data available to me, interest rates have a very limited impact on property sales – population and income growth matter much, much more.

In short, there doesn’t seem to be much of anything going on right now to justify a rapid increase in interest rates. What BNM is really doing is trying to peer through a half-obscured crystal ball and trying to head off potential asset price bubbles, but with the trade-off of slowing growth in the interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy despite an economic recovery that still isn’t fully settled.

I’ll leave this post with one further nugget – money velocity (read this post for fuller details) still hasn’t recovered to pre-crisis levels:

In fact, the rate of change in the velocity of monetary aggregates is still negative (log annual changes):

Juxtaposing this with money supply and economic growth suggests that far from being expansionary, monetary policy is in reality still too tight:

On the other hand (you knew that was coming, right?) here’s an alternative viewpoint, from a highly respected economist who was one of the very few to foresee the financial crisis in the US:

Monetary Policy or Fiscal Policy

...Perhaps more worrisome is the view that the main problem is aggregate demand is too low. In response to ultra-low interest rates, the thinking goes, households will cut back on savings while firms will invest more, demand will revive, and the workers who have been laid off will be rehired.

But this recession is not a “usual” recession. It followed a period of ultra-low interest rates when interest sensitive segments of the economy got a tremendous boost. The United States had far too much productive capacity devoted to durable goods and houses, because consumers could obtain financing for them easily. With households recovering slowly from the overhang of debt resulting from the binge, and with lenders extremely risk averse, it is unrealistic to expect households to spend beyond their means again, and unwise to try to tempt them to do so...

...Put differently, the productive capacity of the economy has shrunk. Resources have to be reallocated into new sectors so that any recovery is robust, and not simply a resumption of the old unsustainable binge. The United States economy has to find new pathways for growth. And this will not necessarily be facilitated by ultra-low interest rates.

What many people forget is that interest rates are also a price, and shape not only the level of economic activity but also the allocation of resources and the relative wealth of buyers and sellers of financial savings. A sustained period of ultra-low interest rates will favor the segments of the economy that took us into the crisis – housing, durable goods like cars, and finance. And it will encourage households to borrow and spend rather than save. With policies focused on reviving the patterns of behavior that proved so costly the last time around, it is ironic that President Obama wants the rest of the world to change and spend more to displace the United States as spender of first resort, even while the United States is unwilling to make any changes itself.

Put differently, aggregate demand is indeed insufficient to restore the economy to old patterns of production. But that production was absorbed only through an unsustainable debt-fueled, asset-price-boom-supported consumer binge. And even if we think U.S. consumers have become excessively cautious (it is hard to see a savings rate of 5 percent as excessive caution, except in relation to the extravagant past), moving them back down the same path seems unwise.

More important, the United States also has a problem of distorted supply. Prices in the economy should reflect the past misallocation of resources and move resources away from areas like housing and finance. A lot of people have to be retrained for the jobs that will be created in the future, not left lamenting for the jobs they had in the past. A Fed that keeps real interest rates at a sustained negative level will stand in the way of the needed reallocation.

None of this is to say that the Fed should jack up interest rates quickly without adequate warning, or to extremely high levels. There are trade-offs here, between short-term growth and long-term misallocation of resources, between reducing risk aversion and inducing excessive risk taking, between reviving hard-hit sectors and encouraging repeated bad behavior. On balance though, if and when the jitters about Europe recede, it would be prudent for the Federal Reserve to start paving the way towards positive real interest rates.

Interesting, no?